Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

A message to the New Creation…

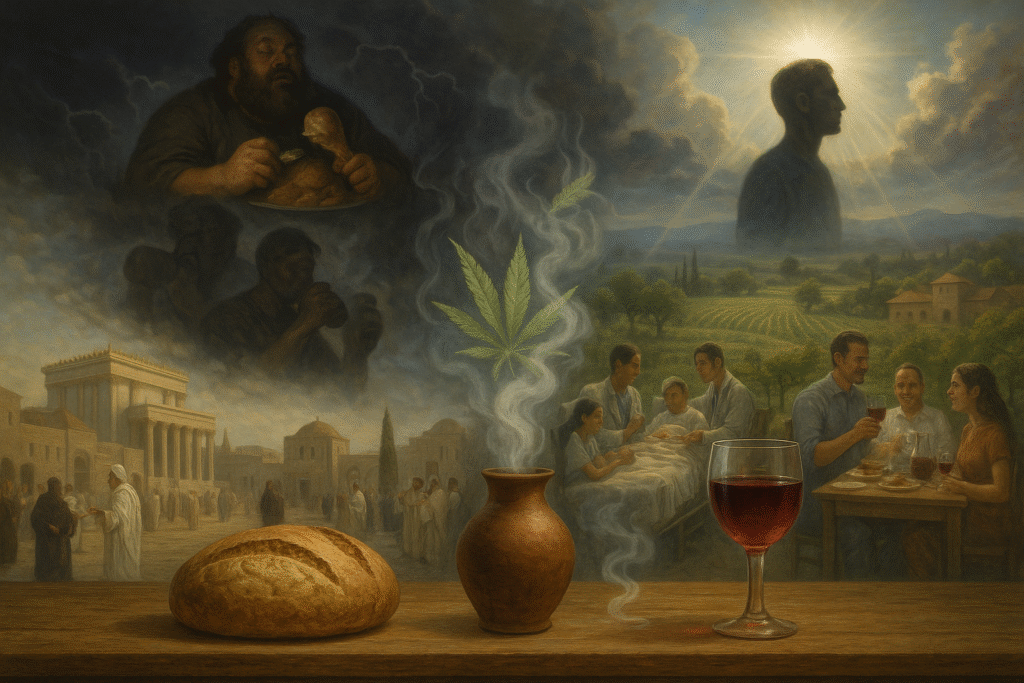

Every generation inherits a stack of taboos dressed up as theology, and every generation must decide whether to keep wearing the costume or return to truth. When we follow the text, the language, and the world that birthed it, a cleaner picture emerges: the Scriptures were not written to police objects but to govern appetites; not to sanctify or demonize substances as such, but to demand the sober stewardship of a human being made to house the presence of Yahweh. The New Testament world of Yehoshua (יֵהוֹשֻׁעַ) was soaked in bread, wine, oil, and the scent of resinous smoke, because that is what life in first-century Judea and the greater Mediterranean actually looked like. Wine was not a scandal; it was the table. Bread was not a prop; it was the day’s anchor. Incense and aromatics were not curiosities; they were the air of temple, synagogue, and home. And in that very world, the apostolic voice does not outlaw wine; it outlaws intoxication, excess, loss of mastery. The command is νήφειν—be sober-minded, keep your head, maintain disciplined clarity. The issue is not the liquid in the cup but the lordship over the cupbearer.

Consider the texture of their days. Wine, fermented and real, ran through weddings and Sabbaths and Passover tables, and yes, it could intoxicate if abused. That is precisely why dilution was common; households cut wine with water in ordinary ratios to make daily drinking sane and sanitary in a world where untreated sources could betray you. Yehoshua’s first sign at Cana did not mint a new liberty; it simply turned a failing wedding into a full one, and the steward praised the vintage because the wine was wine, not symbolism. The Last Supper did not invent a beverage; it consecrated the normal—bread and the fruit of the vine—into the eternal. And when some sneered on the morning of Shavuot, accusing the disciples of being “full of sweet wine,” their taunt only makes cultural sense inside a society where wine was assumed, valued, and—when mishandled—mocked. This is the world in which the Spirit says through Kēphas (Petros): be sober-minded, be vigilant, because your adversary prowls for those who have traded clarity for stupor. The vocabulary matters. νήφω is not a teetotaler’s slogan; it is the steady gait of a mind that refuses to be mastered by what was meant to be a servant.

That same world breathed aromatics. Frankincense and myrrh were not merely liturgical; they were economic and medicinal, traded, burned, infused, and applied. Hyssop, laurel, thyme, sage—these were not boutique herbs but the pharmacy of the ancient household, falling under the practical intelligence of mothers, midwives, and physicians from Judea to the Aegean. The censer was not a fog machine; it was the purifying breath of a sacred space and, incidentally, of a sickroom. The line between ritual and remedy was not as hard as our modern categories demand, because life in an embodied world refuses our false divorces. When Yahweh legislates worship with incense and oil, He is not capitulating to novelty; He is speaking in the language of a people whose daily senses—taste, touch, smell—were already fluent in these substances.

Now place beside that world the modern one, where we have isolated molecules, named receptors, and turned folk knowledge into pharmacology. Red wine’s polyphenols and flavonoids do what ancient experience intuited: they tend vessels, modulate lipids, and carry anti-inflammatory weight—when kept within the boundary that keeps a steward a steward. Push beyond that order and the same compound that sang becomes a whip. No one needs the World Health Organization to tell them what graves already preach: alcohol, abused, kills by a thousand doors—liver and blood and bone and steel—because what was meant to be mastered turned around and mastered its master. The Scriptures never said wine was evil; they said drunkenness was, because drunkenness is a species of idolatry: the enthronement of a sensation over the will anchored in Yahweh.

Enter the modern lightning rod: cannabis. The ancient world knew the plant; our world knows its chemistry. THC engages the central nervous system in ways that can calm pain and twist perception; CBD slips toward anti-seizure, anti-inflammatory, and anxiolytic lanes with little of THC’s intoxication. We have learned enough to craft medicines for spasticity, chemotherapy-induced nausea, wasting syndromes, and certain seizure disorders. We have learned enough to know that while cannabis does not, by itself, shut down the brainstem as opioids do, THC in high doses will fog the mind and slow the body in ways that cannot wear the name νήφω with a straight face. The lesson is not that cannabis is holy or hellish; it is that human appetites require a throne, and when the throne is vacant, something else will sit down.

But if we are going to cut through superstition and selective outrage, we need a constant to test our moral algebra, and the only honest constant is food. You do not need wine to live. You do not need cannabis to live. You do need food, and that is precisely why food exposes the lie that morality is about naming bad objects instead of judging disordered loves. Food is life-giving, sacramental in its ordinariness, and destructive when grasped in excess. Overindulgence in food can harden arteries as surely as spirits can harden hearts; it can choke breath at midnight as surely as liquor can drown it at dusk. It can cloud the mind, inflame the emotions, and kneel a will under cravings that no longer ask permission. Scripture has a name for this: gluttony. Not calories; idolatry. Not plates; appetites. If the most necessary substance in creation can become a sin by measure and motive, then the axis of judgment cannot be the substance itself. It must be the surrender of sober mastery that turns gift into god.

This is why the New Testament’s ethic never collapses into a list of banned items but insists on a way of being. “Keep sober in spirit.” “Be of sober mind.” “Let us be sober.” The grammar sits in the person, not in the pantry. When the apostolic voice warns against drunkenness, the target is loss of governance—whatever the vector. Wine can do it. THC can do it. A bottle of cough syrup can do it. Porn dopamine loops can do it. Gambling endorphins can do it. The object changes; the anthropology doesn’t. The human person is designed for indwelling—breath of Yahweh in dust—and anything that steals the helm steals the voyage. Moderation, then, is not a tepid middle; it is the active discipline of a priestly body. Discernment is not permission to try everything; it is the trained capacity to say yes to what serves the call and no to what enslaves it.

So we speak plainly. Smoking marijuana is not, in itself, a sin. Drinking wine is not, in itself, a sin. Eating food is not, in itself, a sin. The sin appears where mastery disappears. Gluttony is sin because it enthrones appetite. Greed is sin because it baptizes grasping as wisdom. Lust is sin because it converts persons into consumables. The same pattern holds with substances: when a thing designed to be a tool becomes a tyrant, you have crossed from stewardship into idolatry. And while cannabis does not carry a recorded trail of lethal overdoses by toxicity, it certainly carries the power to fog the mind and erode vigilance at sufficient doses, just as wine carries the power to take life in both slow and sudden ways when excess becomes the rule. The wise do not argue that because one knife is duller than another it may be waved at the eye; the wise keep their eyes.

History helps our honesty. If wine, incense, oils, and herbs filled the homes and the holy places of Yehoshua’s world without bearing the blanket label of sin, then the mere presence of a substance is not the moral scandal some would make of it now. What was condemned then remains condemned now: the loss of sober clarity, the indulgence that blurs vigilance, the appetite that rules the ruler. What was embraced then remains to be embraced now: thanksgiving without bondage, celebration without slavery, medicine without the abdication of mind, table fellowship under the banner of a clean conscience. The same Spirit who inspired νήφω also breathed a Church that broke bread with joy and sincerity of heart. If your practice—of eating, drinking, medicating, or celebrating—delivers you into fog and forfeiture, you are not walking in the Spirit’s imperative, whatever name you write on the label.

And because discernment is the keystone, let us refuse stupidity masquerading as freedom. This is not a license to shovel, sip, smoke, swallow, or shoot whatever a culture markets. This is not an excuse to pretend your chemistry cannot harm your neighbor. This is not a clever way to sanctify what is obviously destroying your life. Discernment asks hard, adult questions in the presence of Yahweh: does this serve the call on my life, my body, my mind, my community? Does this preserve νήφω or puncture it? Am I the steward here, or have I quietly become the servant? If your history, your vulnerabilities, your season, your medications, your responsibilities, or your calling demand abstinence, then abstinence is wisdom, not weakness. If moderation is possible, then moderation must be governed, practiced, and proved. Self-discipline is not a mood; it is a muscle.

This is also why hypocrisy must die. We live in an age that will tolerate caffeine jitters baptized as productivity while shaming a cancer patient’s THC tincture, an age that will canonize gluttony as fellowship while crucifying a glass of wine as rebellion, an age that will applaud the pharmacy’s synthetic while scorning the garden’s leaf. None of that is holiness. Holiness is ordered love. Holiness is a will that bows to Yahweh’s voice, not to a substance’s whisper. Holiness is the courage to call sin what it is when appetite becomes altar—whether the idol is a pastry, a pipe, or a pour.

So here is the clean line, drawn with historical honesty and medical clarity and biblical fidelity. Substances are tools; people are temples. The covenant ethic of the New Testament does not sanctify or demonize grapes or leaves; it sanctifies bodies for vigilance and service. Yehoshua ate, drank, and anointed within the customs of His people and condemned neither cup nor oil; He condemned the heart that traded the Father’s will for a feeling. The apostles did not forbid wine; they forbade drunkenness. They did not ban the pharmacy of herbs; they banned surrendering the helm. And the constant that exposes every counterfeit—food—proves the case beyond evasion: even the necessary can become idolatrous; therefore the object cannot be the axis. Mastery is.

Let the indoctrination of man be destroyed, then—the reduction that mistakes lists for holiness and taboos for truth. Let the revelation of substance be restored to its proper place: gifts to be received with thanksgiving and governed with vigilance. Eat, but do not worship your hunger. Drink, but do not drown your mind. Medicate, but do not abdicate your will. Keep νήφω as your watchword, not as a loophole but as a life. And when you stand at the table or the counter or the bedside, remember that Yahweh has not asked you to fear the thing in your hand; He has asked you to fear the throne in your heart. If that throne is filled, the cup will not own you, the smoke will not lead you, and the plate will not name you. If that throne is empty, no law against a leaf will save you.

The conclusion writes itself because the evidence has already spoken. Wine is not sin; intoxication is. Marijuana is not sin; stupefaction is. Food is not sin; gluttony is. Discernment is not optional; it is the daily liturgy of a priestly body. Moderation is not mediocrity; it is royal self-government. Those who are weak to the flesh do not have a “substance problem”; they have a sovereignty problem. Fill the throne. Guard the helm. Walk in νήφω. And let the world see a people whose freedom is not the liberty to consume, but the power to refuse idolatry in any form it takes.