Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

Food for thought….

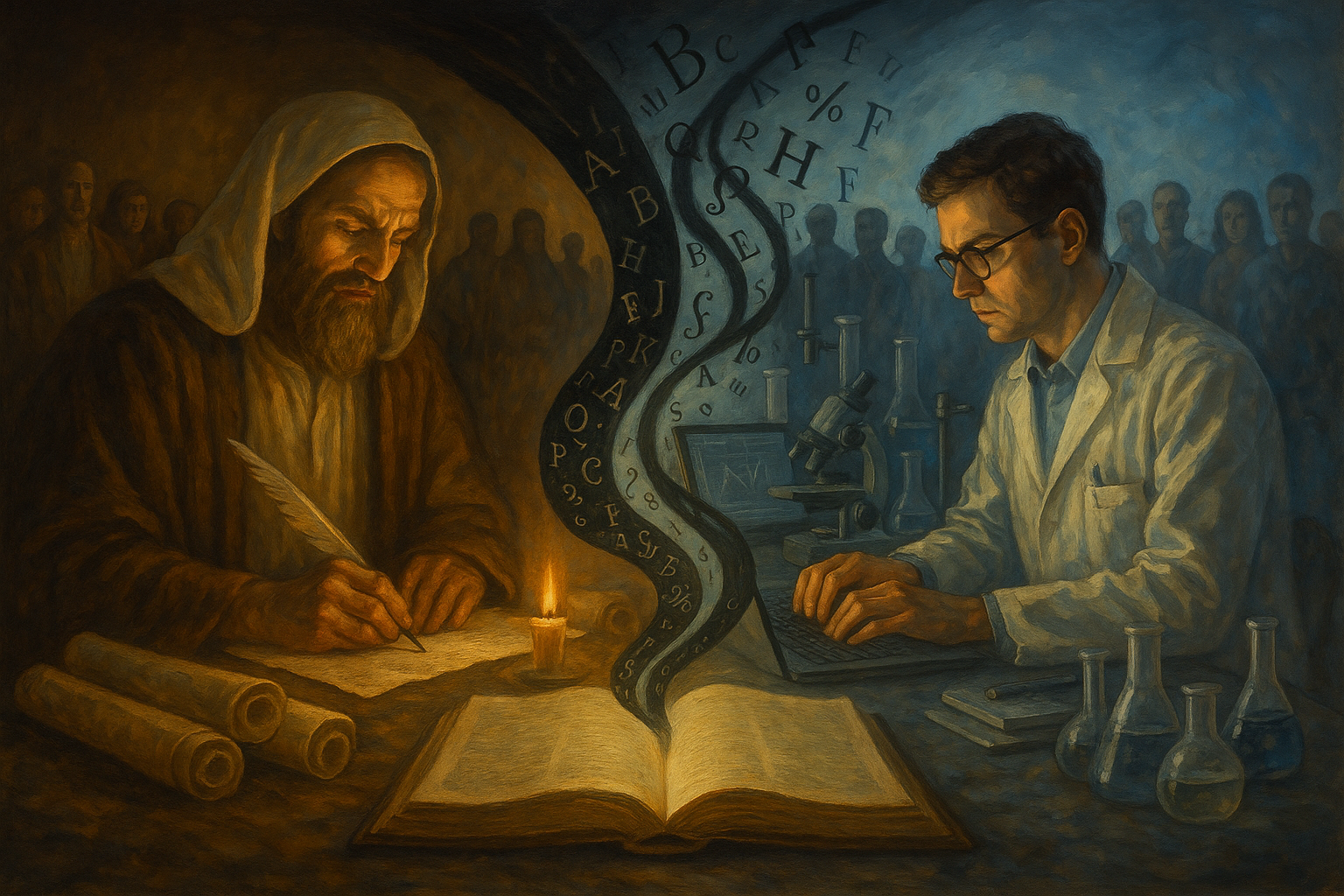

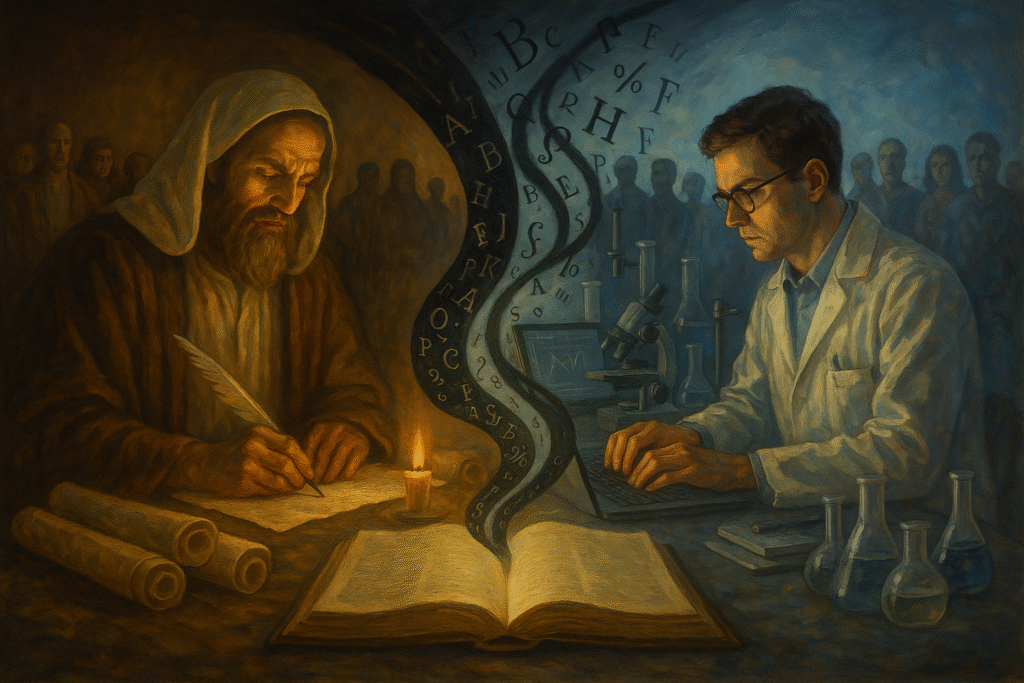

There is a paradox that hides in plain sight, one that is so ordinary most never even pause to notice it, and yet when revealed, it cuts straight through the illusion of certainty that governs both religion and academia. It is the irony that the religious man is mocked for putting faith in the Bible while the academic is praised for putting faith in the textbook. The parody is that both are functioning on the exact same principle—trust in writings they did not personally verify. Both take the words on a page as true without retracing the experiments or re-living the events. Both put faith in unseen processes. The only difference is that one man’s faith is called superstition, while the other man’s faith is called education. But when the veil is pulled back, the ground they both stand upon is the same: eyes fixed on a text, faith in the unseen that produced it.

The Bible claims to be divinely inspired, carried by prophets, apostles, and eyewitnesses. It compiles testimonies, genealogies, letters, poems, and visions—all recorded for instruction and remembrance. The believer receives it by faith because they did not walk with Moses as he parted the waters, nor did they stand in the crowd when Yehoshua raised Lazarus from the dead. They cannot reproduce Sinai in a laboratory. The authority rests in the witness of the text, not in the replication of the events. The Bible is the distilled testimony of those who claimed to have seen and heard, and those who believe are asked to receive their words as true.

The textbook likewise is compiled by authors, editors, and institutions. It claims to be academically inspired, carried by researchers, peer reviewers, and professors. It compiles studies, equations, and theories—all recorded for instruction and remembrance. The student receives it by faith because they did not run the experiments themselves, nor did they sit in the laboratory when the data was first produced. They cannot replicate CERN’s particle collider in their garage or re-run the entire genome project in their living room. The authority rests in the witness of the text, not in the replication of the events. The textbook is the distilled testimony of those who claimed to have seen and measured, and those who study are asked to receive their words as true.

The defense of both Scripture and academia rests on a similar scaffolding: “We have witnesses.” The Bible appeals to apostles, prophets, disciples, and communities who saw, heard, and touched the events. Academia appeals to researchers, scientists, and reviewers who measured, tested, and documented the experiments. Each insists their claims are reliable because they are not solitary voices but communal validations. The Bible says, “This was not done in a corner,” and science says, “This was not done without review.” Both operate by pointing to a chain of testimony.

And yet here lies the irony. In both cases, what the ordinary man receives is not the raw event but the text. He does not stand at the tomb when it is empty, nor does he sit in the accelerator chamber when particles collide. He does not hear Paul thunder on Mars Hill, nor does he calculate the raw datasets behind the climate model. Instead, he receives the testimony about those who did, and that testimony is mediated through written text. The raw event is gone; the record remains. The believer clutches a scroll, and the student clutches a textbook, but both are in the same position.

Academia boasts of peer review. The research of one is examined by others who supposedly verify the soundness of the process and the integrity of the conclusion. This is its safeguard, its claim of authority. The prophet or apostle, too, was reviewed, though not by modern institutions but by communities, councils, and fellow witnesses. Paul’s letters were circulated and tested by other assemblies. Prophetic words were weighed in the synagogue. Torah scrolls were copied with precision, checked letter by letter. In both realms, the word of one was subjected to the eyes of others, and the verdict of many was considered a sign of trustworthiness.

Yet in the end, the pattern is the same. The student does not see the peer reviewers review, nor does the believer see the scribes weigh the scrolls. They must take it all on trust, because what reaches their hands is not the living review, but the final inscription. The reviews themselves are as inaccessible as the experiments or the visions. The community testifies that a process took place, but the ordinary man does not observe the process. He only receives the product.

Behind every textbook is supposed to be a trail of empirical proof—labs, studies, methodologies, and raw data. But these are rarely accessible to the average student. The raw notes of Watson and Crick are not in the biology textbook. The full climate models are not in the environmental science class. The replication of experiments is restricted by access, technology, or training. For most people, the laboratory is as inaccessible as the Temple was to the common Israelite. What they get instead is a priestly class of interpreters—the scientists, the academics—who assure them, “Trust the data. We have seen it. Here is your distilled version.”

In religion, the same framework exists. The common man never entered the Holy of Holies. He trusted the words of the prophet, the scrolls read aloud in synagogue, or the letters passed among the ekklesia. “Trust the Word. We have seen it. Here is your distilled version.” The gap between event and observer is bridged by testimony and text, not by direct experience.

This is the paradox: all those layers—eyewitnesses, peers, councils, reviewers—collapse into one thing for you, the reader: a text you are expected to believe. A scroll, a codex, a journal, a textbook. You do not observe the prophet’s vision any more than you observe the chemist’s titration. You only read the after-image. The living flame of Sinai and the live flame of the Bunsen burner are both already cooled, reduced to ink on a page.

So the question arises: if you cannot see the process, why should you believe the product? Why should the student accept the authority of the peer-reviewed study, or the believer the authority of the sacred scroll? The answer is the same in both cases: because the community has conferred authority on it. The peers in science are the credentialed guild of experts; the peers in faith are the prophets, apostles, and witnesses. Both claim a chain of reliability. Both insist that their reviewed word is trustworthy. But in both cases, the common man is shut out of the process and must receive the final written word on faith.

Here lies the unity: both systems—biblical and academic—require faith in testimony. Faith in the reliability of scribes or of peer reviewers. Faith that manuscripts were preserved or that data was accurately reported. Faith that divine revelation was transmitted without corruption, or that institutional studies are free of bias. The only real difference is what one places faith in: a transcendent God, or a human institution. And even this distinction dissolves into common ground, for both sides must still accept that the text is the sole surviving artifact of what once was.

So then, the parody sharpens. You mock the believer for trusting men who wrote centuries ago, yet you trust men who wrote decades ago. You say the believer has no proof of the miracles, yet you have no proof of the experiments. You accept the testimony of reviewers you have never met, even as you scoff at the testimony of apostles you have never met. In both cases, all you truly have is this: a book, a word, a text. You never see how it got there.

Does the absence of direct observation mean the thing did not happen? No. The fact that we do not personally see Yahweh split the sea does not mean Israel did not walk through. The fact that we do not personally see the double-slit experiment does not mean quantum mechanics is false. Both realms contain unseen realities that are mediated through writing. But here is the razor: for Scripture, the unseen event is verified by prophetic continuity, miracles, and historical witness. For science, the unseen event is verified by peer consensus, controlled repetition, and institutional trust. But the ordinary reader is in the same position in both cases: they believe the book.

Thus we arrive at the paradoxical parody. Whether you clutch a Bible or a textbook, you are leaning on writings you did not author, events you did not witness, and processes you did not personally verify. Faith is the invisible ink connecting the lines on the page to your mind. The question is not whether faith is required, but rather: in whom or in what have you placed your faith? One says, “I trust the God who speaks.” The other says, “I trust the man who studies.” And in both cases, you must answer the same question: what proof do you really have, other than the word written before you?

And so this is not a sermon of condemnation, but a recognition of solidarity. Two people drowning cannot condemn one another for being wet. The believer and the student are both soaked in the same condition: they are asked to trust what they have not seen. They are told to believe on the basis of words preserved and reviewed by others. They are bound to the same posture—eyes on a page, heart leaning on faith. The difference is not that one has faith and the other does not, but that each has chosen a different source in which to anchor their faith. And when that realization dawns, the mocking fades, the pretense falls away, and what is left is common ground. Both are human, both are limited, both are reading words they did not write, and both are living by faith.