Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

To Whom it may concern….

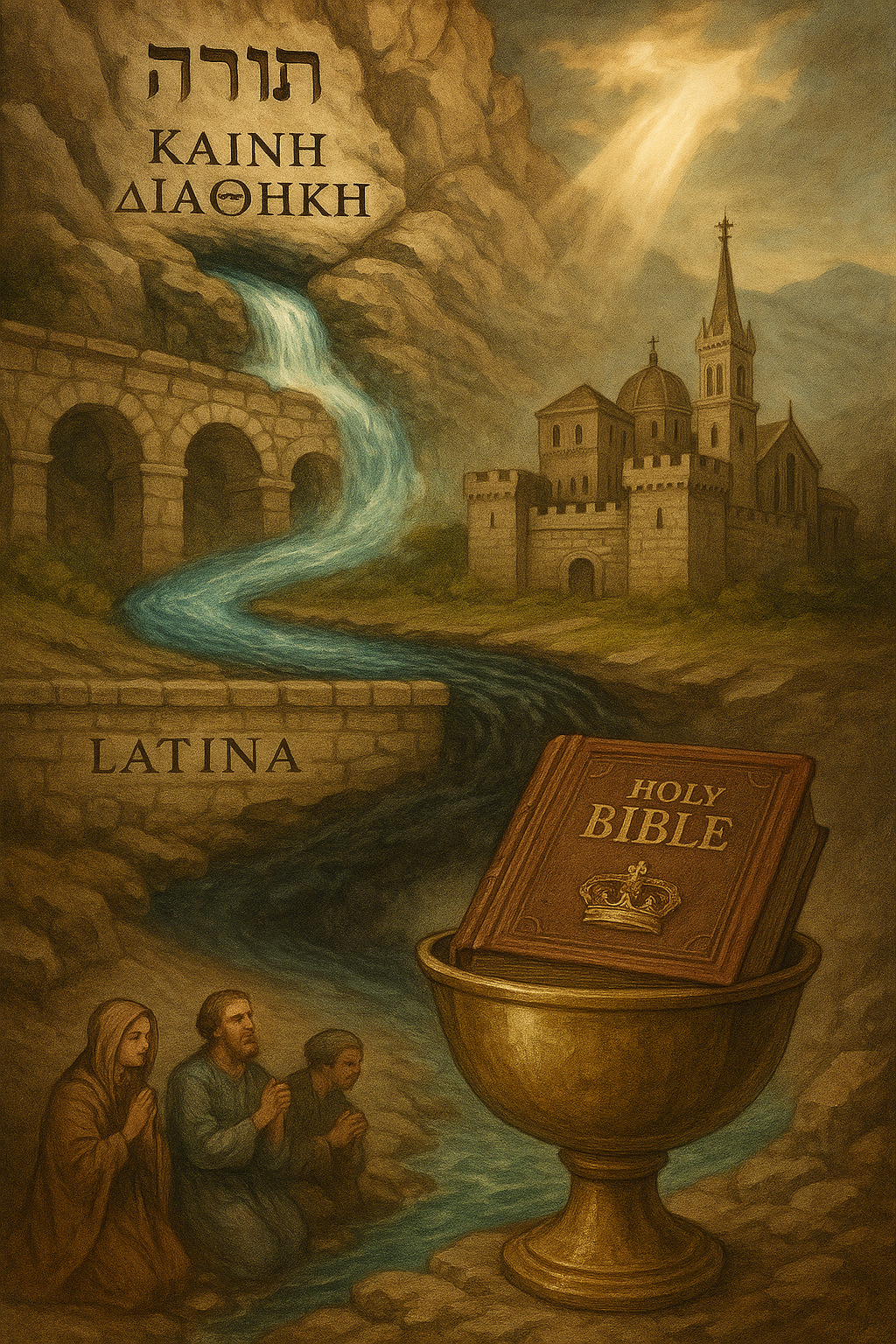

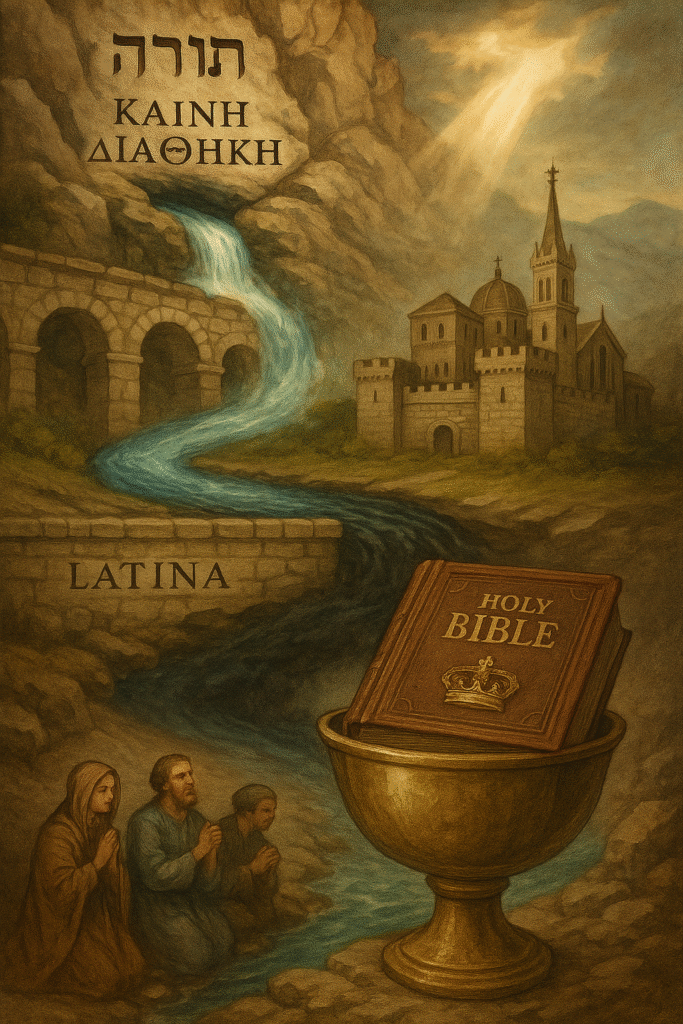

Perspective changes everything. When the Word of Yahweh thundered into the world it did so in the tongues He Himself selected to carry it—Hebrew that binds covenant, number, and image in every letter, and Greek that can lace time, voice, and mood with surgical precision. The Scriptures were completed in those languages by about 95 CE, when the last apostolic line was penned. Then nothing in English for more than a thousand years. That single fact, allowed to rest in the mind without hurry, exposes the illusion of immediacy that modern readers assume: the belief that the book on their nightstand is the same thing that was spoken, heard, and inscribed in the fire of revelation. It is not. Between the living source and the English copy stretches a continent of years, empires, councils, and agendas—enough time to turn a living river into a carefully managed canal.

The Tanakh closed in its covenant tongue by roughly the fifth century before the Messiah, with the prophetic voice of Malachi as a terminal echo in the Hebrew canon. Centuries later, the living testimony of the apostles and their companions was complete by the end of the first century. Take that settled corpus—Hebrew Scriptures completed circa 400 BCE and Greek writings completed circa 95 CE—and mark the calendar forward. The first full English Bible appears in 1382 CE under Wycliffe, not from the Hebrew and Greek but filtered through Latin. That is approximately 1,287 years after the New Testament’s completion. To arrive at the state-sponsored English of 1611 is roughly 1,516 years after the last apostolic ink dried. These are not trivial spans; they are civilizational distances in which languages evolved, institutions hardened, and power learned to harness the sacred for its own ends.

What, then, inhabits that gap? First, a necessary translation bridge: the Septuagint, the Greek rendering of the Hebrew Scriptures begun in the third century BCE, became the Bible of the Greek-speaking diaspora and the early assemblies. Then, as Latin ascended with Rome’s imperial reach, Jerome’s late fourth-century Vulgate became the West’s controlling lens, not because Yahweh ordained Latin as the keeper of His speech, but because empire and ecclesiastical hierarchy did. Across those many centuries the people’s access to the source constricted. Councils determined canons and creeds; bishops determined orthodoxy; princes determined which voices were “safe.” Scripture did not change in heaven, but on earth its mediation was fenced, and the fence was patrolled by Latin literacy and clerical monopoly.

When English finally enters the scene, it does not arrive to the banquet as the heir but as a late guest admitted by gatekeepers. Wycliffe’s 1382 effort, born from the Latin Vulgate, inherits Latin’s decisions, categories, and compromises. Tyndale, blazing the path back toward Hebrew and Greek in the early 1500s, is hunted and executed because returning to the source threatens the economy of control. Coverdale and Geneva advance the cause with courage and craft, but they work under the weather of politics, confession, and exile. The 1611 King James Version—brilliant in cadence, monumental in influence—remains an imperial commission authorized by a monarch to stabilize a realm, harmonize a church, and domesticate disputation. None of this makes English worthless. It makes English a product of its times, tethered to agendas older than most nations and shaped by the priorities of throne and cathedral more than the priorities of Sinai and Galilee.

Language is not a neutral pipe through which revelation flows unchanged. Hebrew compresses cosmos into consonants; each letter is a gate of meaning that opens into number, image, and function. Greek can stack clauses and moods like scaffolding to hold a thought at precise angles so the light can strike it just so. English, by contrast, is a patchwork mercantile tongue that excels in trade and administration but reduces layered sacred architecture to flat floorplans. Translate covenant-rich terms into English and you often get approximations that describe a thing without embodying it. Translate Greek’s tense-voice-mood symphony into English and you often get a melody line without harmony. Then place those approximations under centuries of doctrinal dispute, imperial policy, and denominational rivalry, and the result is not the fountain but a rationed cistern. The tragedy is not that English exists; the tragedy is that multitudes mistake a rationed cistern for the spring.

This is why the belief that “my English Bible is the final, completed Word of God” is not merely naïve; it is historically untenable. Finality belongs to what Yahweh spoke and what His servants wrote in the languages chosen for that speaking and writing. English is a witness, sometimes faithful and sometimes faltering, always downstream. To call it final is to confuse the moon for the sun because the moonlight feels sufficient at midnight. The illusion of finality empowers institutions to present their translation as the ceiling rather than the window. It relieves the conscience from returning to the source and relieves leadership from the accountability that the source inevitably imposes. It is safer to police English sentences than to submit to Hebrew roots and Greek constructions that refuse to be tamed by a single tradition.

The long gap also reveals something darker than mere linguistic loss: the management of access. When a people cannot read the source, they must be told what it says. When they must be told, the teller becomes the gate. Gates can be kind or cruel, but they are still gates. Across the Latin centuries, access to Scripture became a credentialed privilege. When sparks of reform leapt up to carry the text back to the people, the cost was blood. That history should inoculate us forever against the idea that the version in our hand—any version—is beyond question. If brave men and women paid with their lives to peel back mediations, then faithfulness on our side of history cannot be to re-erect the mediations under the pious claim of finality; faithfulness must be to continue the journey back to the spring.

Let the raw arithmetic preach. From approximately 95 CE to 1382 CE is about 1,287 years—thirteen centuries in which the body of Messiah confessed, fought, fragmented, legislated, and imperialized while the English-speaking world had no Scripture in its own tongue. From approximately 95 CE to 1611 CE is about 1,516 years—fifteen centuries to the royal English standard that would dominate the Anglophone imagination. In that time, meanings drifted, terms hardened, and entire theological systems took shape without the ordinary believer ever laying eyes on the Hebrew of Torah or the Greek of the apostles. No honest reader can carry those numbers in their heart and still equate “my English wording” with the living speech of Yahweh without blinking.

If English is not the final word, what is it? At best, it is a window. Windows can be clean and generous, letting you see the mountain; they can also be fogged, scratched, or tinted to flatter the house that installed them. The wise do not worship windows; they look through them. At worst, English becomes a mirror; the reader gazes and sees their tradition’s face and believes it is the mountain. The remedy is not despair but discipline: to honor English for the access it gives while refusing to rest in it as the end. For the New Creation, fidelity is not loyalty to an edition but allegiance to the breath that spoke the words in the first place. That allegiance compels us to cross languages, examine lineages, weigh choices, and repent when tradition has replaced truth.

This reframing does not diminish Yehoshua; it honors Him. He is not served by mistaking convenience for covenant or empire for ekklēsia. He is served when His people love what He said enough to seek it where He placed it, and when they refuse to allow any culture—ancient or modern—to flatten His revelation into a manageable slogan. To say that English is often an inadequate container is not to deny inspiration but to defend it. The breath that animated the prophets and apostles still animates today, but it will not be harnessed to our shortcuts. It waits at the source, in the texts where Yahweh stored it, asking whether we will come and drink.

Therefore the timeline is not an academic curiosity; it is a summons. It tells us that what we hold in English is late, layered, and liable to the pressures of the powers that sponsored, curated, and canonized it. It tells us that calling this late, layered artifact the “final version of God’s Word” collapses millennia of linguistic and spiritual architecture into a thin veneer. It tells us that if we hunger for accuracy, power, and transformation, we must step beyond the veneer and touch the stone—Hebrew letters that carry covenant structure, Greek clauses that bear apostolic nuance, a Name that bears the very identity of Yahweh without dilution.

Here, then, is the perspective the outline intended to force upon the reader: the English Bible is not the fountainhead but a downstream channel, carved across long centuries by the tools of empire, church, and culture. Some channels run clear, some run muddy, and some are diverted to irrigate fields that Yahweh never planted. The solution is neither cynicism nor triumphalism; it is repentance and return. Repentance for equating our convenience with His revelation; return to the languages, contexts, and meanings He chose. Only then can we correct distortions, expose manipulations, and recover the fullness that was compressed into the letters and lines at the beginning.

The conclusion must be as firm as the intro is arresting. The Scriptures were completed by about 95 CE in Hebrew and Greek; the first full English rendering did not appear until 1382 CE, with a state-standard English in 1611 CE. That is a chasm of roughly thirteen to fifteen centuries. Across that chasm, tongues shifted, powers contended, and the text was stewarded, fenced, debated, and deployed. To declare the English result “final” is to sanctify the work of time and throne as if it were the work of Sinai and Spirit. The English Bible can be a faithful witness when handled humbly and checked relentlessly against the source; it becomes a gross misrepresentation when enthroned as the source itself. The path forward for the New Creation is not to discard English but to dethrone it, to treat it as a window and not a wall, and to lead a generation back to the mountain where the Word was first heard—so that what we proclaim is not the echo of empire, but the living voice of Yahweh.