Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

Is religion just another form of control? ……Yes.

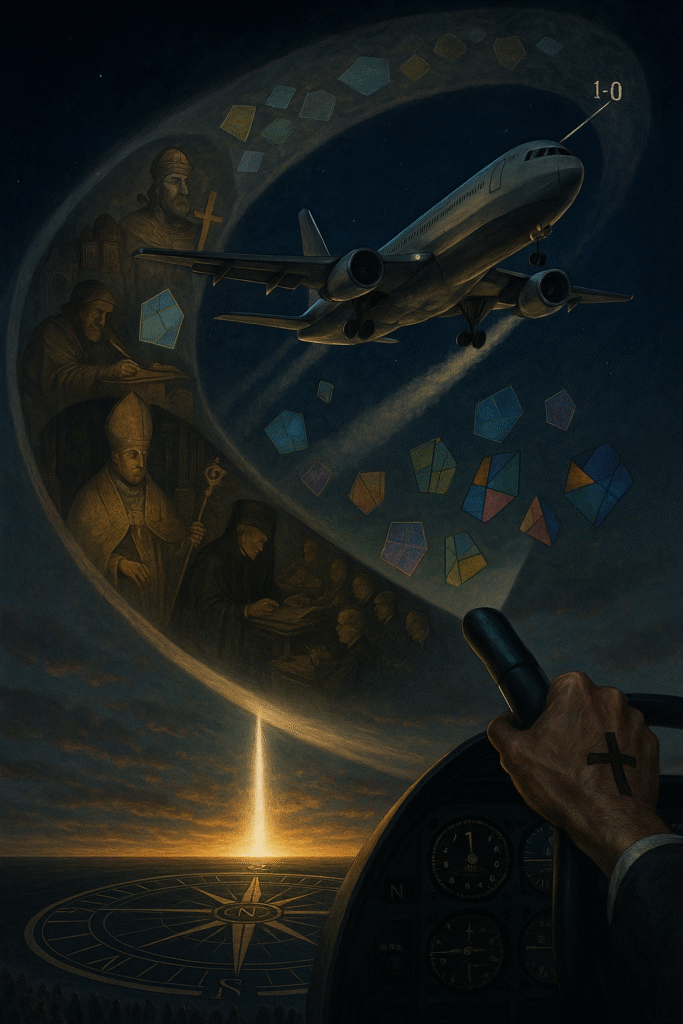

I want to start by telling the truth plainly: when an atheist says “religion is control,” he’s not wrong—he’s just describing the fruit without seeing the root. Control rarely begins with a hammer; it begins with a whisper. It begins with what I call the one-degree parable: the god of substitution, the father of lies, almost never tears truth in half in front of you—he nudges it by a single degree and then lets time do the heavy lifting. Think about a plane set by Yahweh on a straight course at five hundred miles per hour; change the heading by one degree and leave it that way. After one year, you’ve flown 4,382,910 miles and you are already 76,492 miles off your true line. After five years, your lateral drift is 382,462 miles. After ten years, 764,923 miles. After twenty years—without any further tampering—you are 1,529,847 miles off course, more than six times the distance from the earth to the moon. A tenth of a degree—just a tenth—still puts you about 153,000 miles off after twenty years. That’s how substitution works. It’s a subtle tilt multiplied by time until the counterfeit destination looks like the only map anyone remembers. And that is precisely how we ended up with a counterfeit religion, a counterfeit text in places, and a counterfeit name bearing the weight of systems Yahweh never authored.

Follow that tiny bend back to its root and you meet Constantine, the emperor who merged imperial power with a Hebrew, Spirit-born faith and rebranded it as a Roman institution. The records that survive show his intent in his own words. In the aftermath of Nicaea, the emperor circulates a letter about the calendar for Pascha and says, “Let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd,” separating the assemblies from the very Hebrew people through whom the oracles of God came. That line—“nothing in common”—is not a stray insult; it’s a policy statement, a blueprint for severing covenant roots so that Rome could own the tree. Once you separate a people from their language, their calendar, their names, their ways, you have replaced relation with religion; you have traded a living vine for a managed trellis, and control becomes easy because you’ve lifted the faith out of its original soil. The Nicaean language is preserved by Eusebius; we didn’t imagine it. The one-degree shift there is the shift from “we are grafted into Israel’s covenant” to “we shall have nothing in common with them.” Give that a few centuries and the drift becomes a world.

Out of that imperial merger grows the institution later consolidated as the Roman Catholic Church, complete with papal supremacy, clerical hierarchies, and mechanisms for controlling not only doctrine but the very access to Scripture. The Council of Trent’s fourth session (1546) declares the old Latin Vulgate to be the “authentic” edition in public lectures, disputations, sermons, and expositions—no one is to presume to reject it. The policy intent is crystal: fix the authorized text and route understanding through the magisterium. In a largely illiterate Europe, that decision doesn’t just name an edition; it assigns custody of meaning. The drift deepens: Scripture moves from common bread to sacramental ration. The point here is not to caricature every monk or priest; it’s to show how the one-degree principle was institutionalized: centralized authorization, restricted access, and the benign story that this is all for your good. Control smiles while it narrows the gate.

Even the word “Christian” itself tells on the process. Scripture uses it three times—once in Antioch as an external label, once in a courtroom exchange, once in exhortation about suffering—not as a covenantal name Yahweh speaks over His people, not as the core identity term the apostles adopt for themselves. “Christianity” is not a biblical word at all. The point isn’t to quibble over labels; it’s to show how an outsider’s handle can harden into an empire’s brand. A nickname became a religion; a movement became a managed category. That is the one-degree parable at work inside a single word.

But long before Trent, another crucial bend was already in the timber: translation choices that quietly flattened Hebrew distinctions. The Septuagint—the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures made for Hellenistic Jews—arose under Ptolemaic patronage. The “Letter of Aristeas” frames the story with royal librarianship and seventy-two translators brought from Jerusalem; whether or not every narrative detail is exact, the historical result is clear: a Greek Bible for a Greek-speaking diaspora. That solved a pastoral problem while creating a linguistic one: languages don’t map one-to-one, and power dynamics in a culture tend to pull meanings toward their own categories. In Hebrew, ish can mark a man as a bearer of position or recognized standing, a man of power. While zakar marks a male as biological sex, a subordinate, not necessarily of status or title or power. The context is also in the household covenant. Which could be referred to a father to a son or to a servant or to a slave. The man or the head of the household as compared to a subordinate. In the Levitical holiness code, both terms matter in context. In the LXX, zakar consistently becomes arsen (male), while ish is often rendered by anēr (man) or anthrōpos (human), which can be serviceable but can also collapse social and covenantal nuance in certain contexts. That collapse may not have been malicious; it was, however, consequential, because the Greek lexicon became the scaffolding for later readings that no longer “heard” the Hebrew layers. Once again: one degree.

This matters intensely when you reach the New Testament’s vice lists. Paul uses malakoi and the very rare arsenokoitai. Most scholars acknowledge that arsenokoitai likely draws directly from the LXX’s wording of Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13—arsenos (male) + koitē (bed)—either coined by Paul or adopted from Hellenistic Jewish usage. That much is philologically plausible. But what those terms refer to, in lived social practice, has been debated for decades: exploitative sex, pederastic systems, temple prostitution, coercive household abuse, economic predation, or a blanket ontological category. Even scholars who argue for sweeping condemnation admit the term’s rarity means context must do heavy interpretive work. Here is where the earlier one-degree flattening bites: when the Hebrew world of status, power, and covenant boundaries is collapsed into generic Greek “male-bedding,” later translators can import modern categories that the text did not specify. Category control rides on lexical flattening, and the result is that a passage policing exploitative, hierarchical violations can be made to police an entire modern identity. That’s control by vocabulary.

Now watch the drift in the modern period accelerate. The nineteenth century coins a new sexological vocabulary: in 1868–69, Károly Mária Kertbeny uses “homosexual” in private correspondence and then publicly in 1869. That is not a biblical word; it is a modern category. In 1946, the first edition of the Revised Standard Version applies “homosexuals” to 1 Corinthians 6:9; the RSV committee later revises its rendering, acknowledging problems with the term. From that single decision, entire churches and civil regimes built policy, discipline, and shame. Whether one applauds or laments that history, the point for our purpose is the mechanism: a modern label was retrofitted to an ancient text through a translation choice, and for a crucial slice of the twentieth century, that choice functioned as a lever of conscience. That is one degree in the machinery of control—small at the moment of decision, massive over decades.

The same pattern shows up in soteriology vocabulary. The Greek aphesis (and the verb aphiēmi) carries a liberative core—release, remission, letting go, cancellation of debt. When Yahweh in Messiah proclaims “release to the captives,” the word is aphesis. But in some English ears, “forgiveness” became chiefly a moralized ledger entry—feel bad, be better, beg pardon—drifting away from the image of gates unlocking, chains falling, debts erased, prisoners walking out under open sky. The shift is subtle; it is not that “forgive” is wrong, it’s that the liberating density of aphesis can be thinned to guilt management, which is far easier for institutions to ration than freedom is for the Spirit to give. Translate a jail-door as a handshake, and you will train a people to love their cell. One degree.

Names tell the story most viscerally. The Hebrew covenant name Yehoshua—“Yahweh saves”—appears in shorter late forms as Yeshua; the Greek Iēsous is a transliteration necessity in a language without a “sh” sound and with masculine endings; Latin Iesus carries it forward; English “Jesus” emerges after the I/J distinction stabilizes in the early modern period. Historically, that linguistic pathway is straightforward and not inherently sinister. But the effect of centuries of detachment from the Name’s covenant density is real: what was originally a name that carried the very syllables of Yahweh’s saving identity became, for many, a sound divorced from its Hebrew freight. The drift here is not a conspiracy of vowels; it is the loss of covenant memory—the pruning of a Name from its root so thoroughly that whole cultures can chant it without any sense of what it carried in the first place. A small phonetic step multiplied by time became a theological amnesia.

Tie these threads together and you can see the system. The root is imperial: Constantine’s merger, explicit separation from the Jews, the Romanization of a Hebrew faith into “Christianity” as a state-shaped religion. The trunk is linguistic and institutional: the Septuagint’s necessary but flattening bridges; the Vulgate’s official status; later state-authorized translation projects like the King James with rules shaped in the wake of Hampton Court, which, among other things, instructed a revision constrained by existing ecclesial phrasing. The branches are specific lexical decisions that reach deep into people’s lives: aphesis narrowed to “forgiveness” as mere guilt relief; malakoi and arsenokoitai read through twentieth-century categories; and identity labels like “Christian” wielded as badges of belonging to an institution rather than signs of being grafted into Israel’s covenant Messiah. The fruit is what your atheist friend sees: religion as control. But that fruit grew from a one-degree bend at the root, multiplied by centuries until the counterfeit seems original.

If you need another picture, think of a prism. The pure white beam is the Word as given in the original tongues and covenants. Every time it passes through a translator’s glass, it refracts a little—sometimes helpfully, sometimes not. But place that glass in a palace, in a council chamber, in a chancery, and the angle of that glass can be set by men with interests. The congregation at the end of the room doesn’t see the glass; they see the colored light on the wall and call that light “Bible,” not realizing how different it looks when you shift the pane by one degree. Or think of a bank ledger. In Scripture, “release” is a zeroing of the debt; in institutional control, “forgiveness” can become a subscription—pay the minimum each month, accrue interest in shame, never actually leave the debtor’s prison. None of that requires a single overt lie; it only requires a series of near-truths, accumulating until the sum total is something God never said.

And because this is not just rhetoric, let’s keep the math in view as we walk the centuries. The first bend—“have nothing in common with the Jews”—is our one degree. By the time the Septuagint’s categories dominate diaspora reading, we have five years of flight and we’re 382,462 miles off our original line. By the time Trent nails down an “authentic” Latin in the sixteenth century, we’re well past the lunar distance. By the time modern sexological vocabulary gets welded onto Pauline lists in the mid-twentieth century, we’re 1.53 million miles laterally displaced. No further malice required—just the stubborn refusal to correct the heading. That’s why I call it the counterfeit Bible and the counterfeit religion wearing the counterfeit name. Not because every translator was a villain, but because the enemy understood the geometry of drift and the nature of man. If he can’t stop the plane, he’ll move the compass by a hair and let the clock do the rest.

So what now? Restoration is not rage; restoration is return. We return to the Name with its covenant density; we return to the languages with tools that can carry weight—HALOT for Hebrew/Aramaic, BDAG for Greek; we return to context so that words like ish and zakar, malakoi and arsenokoitai, aphesis and aphiēmi, speak in their own voices before we impose ours. We audit high-leverage nodes—names and titles, sin and salvation lexicon, household power terms, priest-king vocabulary, Spirit language—and we map their journey: Masoretic Text to Septuagint, to Greek New Testament, to Vulgate, to state Bibles, to modern versions. We don’t do this to score points; we do it to correct the heading. And as we correct, we also loosen the fingers of control: make the sources legible again; let the people see; let the Spirit breathe; let covenant identity replace institutional brand. The goal isn’t to burn the books; it’s to open the windows.

I want to end where we began, with the plane and the whisper. The counterfeit doesn’t need to scream; it needs only to be “close enough” while it dares you to keep flying. But Yahweh did not leave us without instruments. He gave us the Name that saves, the tongues that carry His covenant, the Scriptures that, when heard in their own voice, pull the nose back toward true north. If we will humble ourselves to the math and the mercy—to the geometry of drift and the grace of course correction—we can watch the miles of lateral error collapse as the heading snaps back into line. We can see a people walk out of the prison of “forgiveness” into the jubilee of release. We can see the label “Christian” bow to the reality of a new creation in Messiah. And we can watch religion as control starve for lack of a host, because the Father’s relation has returned to the cockpit. That is the work set before us. That is why I agree without surrendering: religion, as men made it, became control. But Yahweh’s Word, as He gave it, is life. Our task is neither to shout at the tinted light nor to curse the prism; our task is to move the glass, one exacting degree at a time, until the room floods white again.