Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

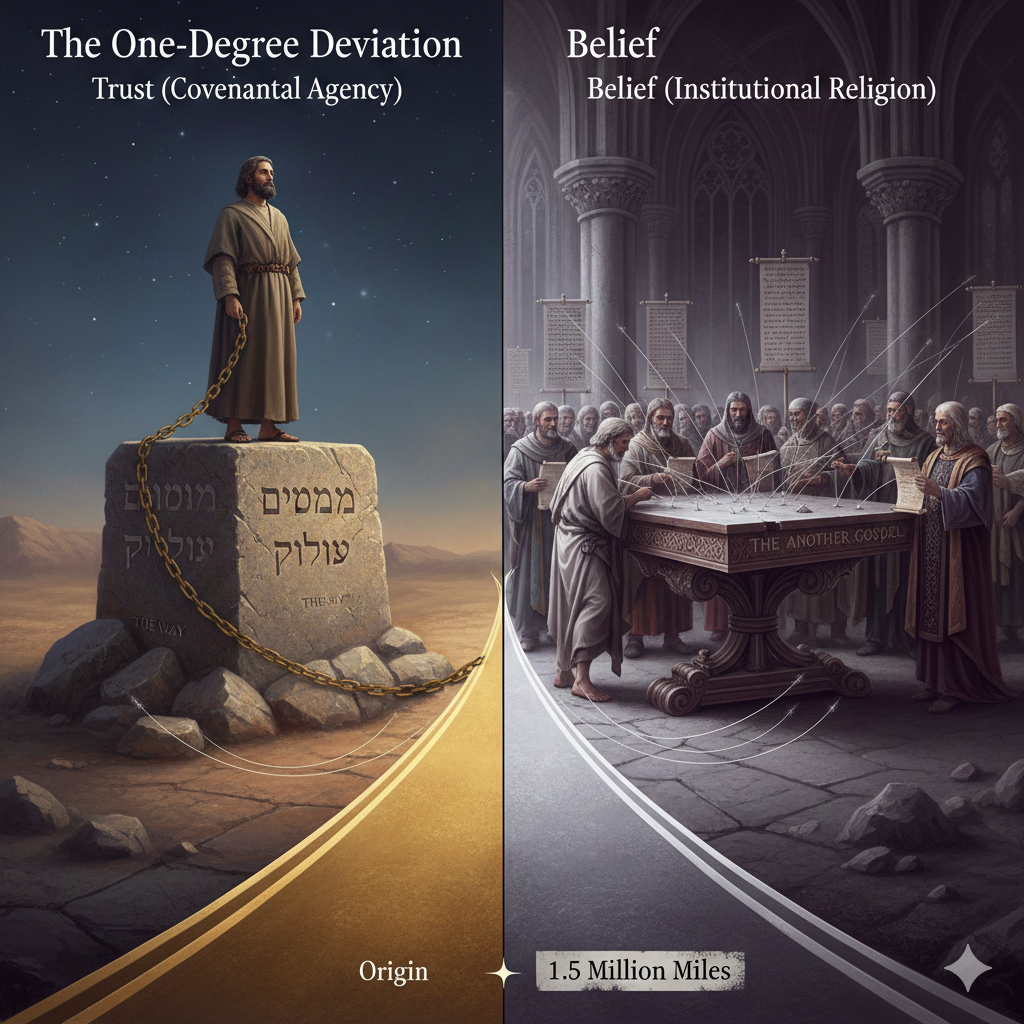

The difference between trust, belief, and faith is not a matter of semantics. It is the dividing line between covenantal relational agency and man‑made institutional religion. The distinction is subtle at the start but devastating in consequence. A single degree of deviation, imperceptible in the moment, becomes catastrophic when carried forward at speed. Take a table made of Foxwood. A material that looks like wood but is not, provides the lens through which this difference can be seen. It appears solid, convincing, and reliable. Yet the test of whether one merely believes it is wood or entrusts weight to it exposes the gulf between projection and reliance. This gulf is the posture shift that has defined Christianity as the “another gospel” Sha’ul warned of. A drift from covenantal trust into institutional belief.

Trust is stance, a position, a foundation to be built upon. It is the act of standing on the table, distributing weight, and embodying reliance. Belief is a projection. However, it is a projection of an assumption. It is the thought that the table might hold, the opinion that it appears strong, the mental exercise of imagining its capacity. Faith in English attempts to merge both, but the merger collapses under its own contradiction. One cannot stand and question simultaneously. One cannot entrust and doubt in the same posture. The New Testament word pistis, used overwhelmingly in contexts translated as “faith,” does not mean belief in the modern sense. It means trust, fidelity, reliance, entrustment. The rare word for opinion or belief, doxa, is almost absent from covenantal contexts. The imbalance is stark: pistis dominates, doxa recedes. Yet English translations collapse pistis into “faith” and “belief,” producing confusion that has shaped entire institutions.

The Foxwood table analogy exposes this collapse. Believing the table is wood is only a projection of thought without action. Believing it can bear your weight is no different, for both remain mental projections untested by trust. To trust the table is to stand upon it, to embody reliance. Faith in English is asked to be both, but the body refuses the contradiction. The analogy clarifies that belief is external, trust is internal, and faith as rendered in English is incoherent. The covenantal call is to trust, not to believe. Scripture confirms this distinction. Ya‘aqov (James) declares that demons believe and shudder. They recognize, they project, they assent, but they do not entrust. Sha’ul (Paul) speaks of the righteousness of God through the pistis of Yehoshua, not through human belief. The covenantal justice flows through His fidelity, His entrustment, His obedience, not through the volume of human projection. Habakkuk declares that the righteous live by emunah, firmness, reliability, covenantal loyalty. Hebrews defines pistis as standing‑under, proof of unseen realities, not projection of opinion. The witness is consistent: covenantal agency is trust, fidelity, reliance. Institutional religion has substituted belief.

To be clear, lets define belief in the English language.

Merriam‑Webster: Belief is “a state or habit of mind in which trust or confidence is placed in some person or thing” or “something accepted, considered to be true, or held as an opinion.”

Cambridge Dictionary: Belief is “the feeling of being certain that something exists or is true” or “something that you believe, such as a religious or political conviction.”

Philosophical (Epistemology): Belief is a subjective attitude that something is true — a mental stance that can be either true or false, often treated as a disposition to act as if something were true.

Belief, as defined across the most authoritative sources, reveals its limitations when measured against the language of trust. Webster describes belief as a “state or habit of mind,” locating it firmly in the realm of mental disposition. Cambridge frames it as “the feeling of being certain,” again emphasizing an assumption rather than a positional stance. Philosophical discourse sharpens the point further, defining belief as a “subjective attitude” toward a proposition. Each definition, though varied in phrasing, converges on the same reality: belief is projection of thought, a mental posture that does not require embodied action.

The distinguishing features of belief confirm this. Belief is mental projection, operating in the sphere of thought and opinion without demanding the risk of reliance. It can range from strong conviction to tentative acceptance, oscillating between certainty and doubt, but always remaining abstract. Unlike trust, which requires reliance and embodied action, belief can remain detached, hovering in the mind without ever touching reality. Unlike faith in English, which attempts to merge belief with trust, belief alone is intellectual assent, a recognition that something might be true without the necessity of standing upon it.

None of these definitions embody the language or action of trust. Belief does not carry the weight of stance, nor the existential risk of reliance. It is recognition without entrustment, projection without embodiment. It can acknowledge strength but never test it. It can confess certainty but never prove it. In this way, belief remains external, fragile, and ultimately insufficient when measured against covenantal agency. Trust demands action. Belief remains thought. The gulf between them is the very posture shift that has defined the difference between covenantal Scripture and man‑made institutional religion.

Now let’s define trust in the English language.

Merriam‑Webster: Trust is “assured reliance on the character, ability, strength, or truth of someone or something”. It emphasizes confidence placed in another and dependence on their reliability.

Cambridge Dictionary: Trust is “the belief that you can depend on someone or something” and “to believe that someone is good and honest and will not harm you, or that something is safe and reliable”.

Philosophical (Epistemology): Trust is described as “an attitude or hybrid of attitudes (optimism, hope, belief) toward a trustee that involves vulnerability to betrayal”. Philosophers distinguish trust from mere reliance: reliance can be placed on objects or systems, but trust involves relational vulnerability and expectation of fidelity.

Trust is not projection. Trust is reliance enacted through embodied action. It is the posture of standing, the distribution of weight, the exposure of vulnerability. Unlike belief, which remains abstract and mental, trust requires evidence of reliability. It is not granted at the outset; it is earned. Trust is not given until trustworthiness has been proven. This is why trust carries relational depth: it is not simply a thought about strength, but the lived reliance upon demonstrated fidelity.

Western institutional definitions often blur trust with belief, describing it as confidence or conviction. Yet in lived reality, trust is something that emerges only after proof. A person is not trusted until they demonstrate that they are trustworthy. A structure is not trusted until it bears weight. In covenantal terms, God does not demand blind projection. He proves Himself faithful, and only then does trust become the natural stance. Trust is therefore not a leap into uncertainty but a response to proven faithfulness. A proven trustfulness.

Abraham provides the covenantal precedent. When he was called to bring Yitzḥaq (Yeets‑khahk) — Isaac — to the mountain, this was not the first encounter. God had already proven Himself to Abraham. He had called him out of Ur, sustained him through famine, delivered him in battle, and given him a son against the barrenness of Sarah’s womb. Each act was proof of fidelity, demonstrations that God was sturdy, reliable, and covenantally faithful. By the time Abraham was asked to entrust his son, he was not leaping into uncertainty. He was standing upon a table that had already borne weight. His trust was not blind belief; it was reliance upon proven covenantal fidelity.

Scripture confirms this posture. In Genesis 22, Abraham rises early, prepares the wood, and sets out for the place God had told him. His actions are trust embodied. He does not project belief that God might provide; he entrusts himself to the God who has already proven His reliability. The covenantal agency is clear: trust is enacted because God has demonstrated trustworthiness. Abraham’s stance is not mental assent but embodied reliance. He stands because God has already shown He can hold.

This is the essence of trust in covenantal Scripture. It is reliance upon demonstrated fidelity. It is the posture of entrustment that follows proof. It is the stance that embodies covenantal agency. Trust is not belief dressed up; it is reliance grounded in evidence. God proves Himself sturdy, and then trust is enacted by standing. This is why trust is the foundation of covenantal relationship, and why belief alone is insufficient. Trust is the lived response to God’s proven faithfulness.

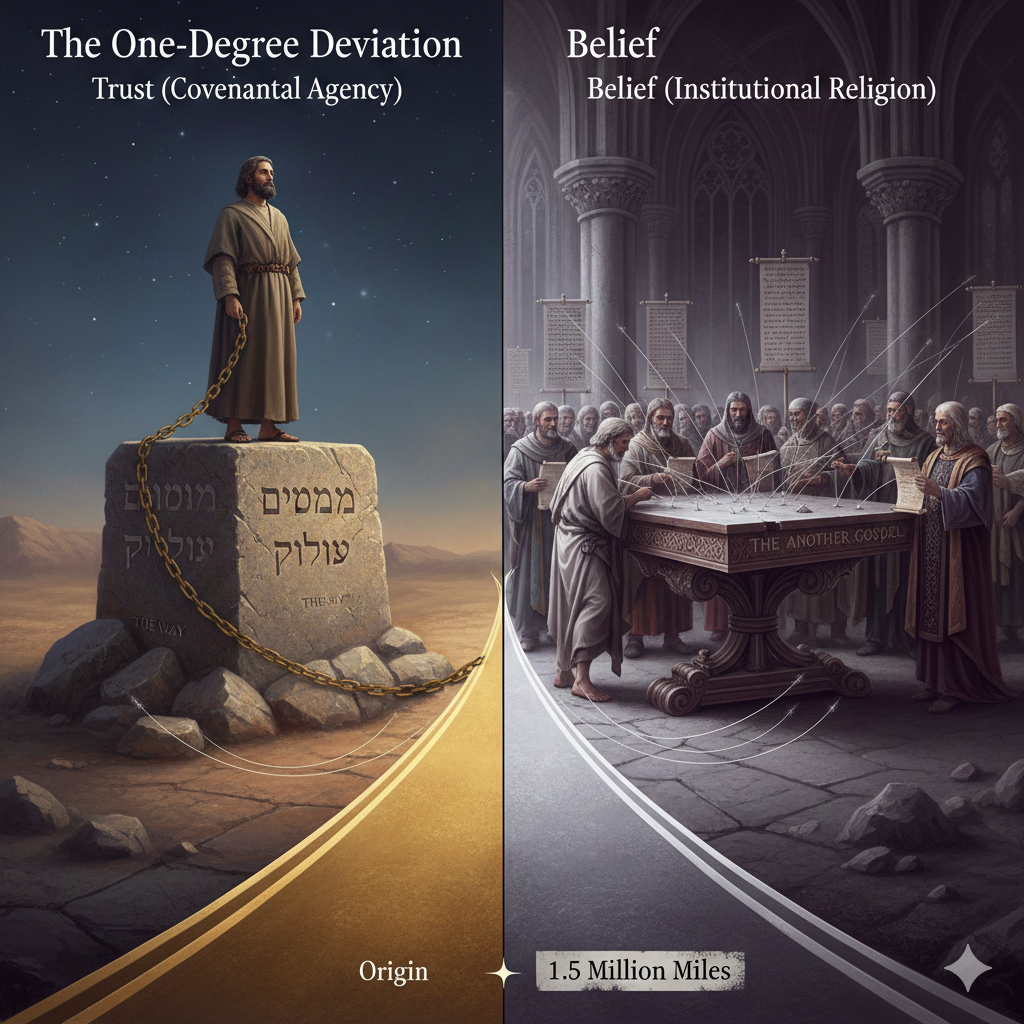

From covenantal relational agency to man-made institutional religion, is a posture shift that can be quantified. Imagine two lines beginning from the same origin. One points at true zero degrees, the other offset by one degree. Both move at five hundred miles per hour. The difference feels negligible at the start. Yet after ten years, the separation exceeds seven hundred sixty thousand miles. After twenty years, the gap surpasses one and a half million miles. The geometry illustrates the covenantal consequence. A subtle deviation in posture, from trust to belief, compounds into catastrophic separation over time. Christianity, as institutional religion, is now one and a half million miles away from covenantal relational agency that is known as “The Way.”. The drift is not cosmetic. It is existential. It is the “another gospel” Sha’ul warned of, a gospel that looks similar but is fundamentally other in posture.

The historical distortion must be named. The Greco‑Roman Catholic invention and the imperial crown of England’s controlled interpretation shaped Christianity into a man‑made institutional religion. This framework substituted belief for trust, confession for fidelity, projection for entrustment. The result is a God conceived as concept, imagined through institutional lenses, confessed through doctrinal statements, but not lived through covenantal agency. The Way, by contrast, is covenantal relational agency. It is the reality of God revealed through entrustment, fidelity, and relational knowing. The difference between concept and reality is the difference between Christianity and covenant. One is projection, the other is presence. One is belief, the other is trust.

The words of Yehoshua confirm the consequence. “Depart from me, for I never knew you.” The charge is not ignorance of facts but absence of relational fidelity. To be known is to stand in trust. To be unknown is to remain in belief. The Foxwood table analogy, the pistis lexical audit, and the one‑degree drift math converge to prove beyond doubt that Christianity is the “another gospel.” A counterfeit religion with a counterfeit name (Jesus) for salvation. A posture shift from covenantal relational agency to man‑made institutional religion. The call is to restoration. The call is to return to trust stance, to covenantal fidelity, to relational agency with the God of Israel. The call is to abandon projected assumption and to embody reliance in a stance. In foundational position of trust.

The conclusion is stark but necessary. The difference between trust, belief, and faith is not academic. It is the difference between being known and being unknown, between covenantal reality and institutional concept, between The Way and Christianity. The posture shift is subtle at inception, devastating in consequence. The numbers prove it. The Scripture confirms it. The analogy illustrates it. The testimony embodies it. Christianity is the “another gospel.” The Bible as institution is the “another gospel.” Covenant Scripture (Ex: Aleppo, Leningradensis / Sinaiticus, Vaticanus codices) is relational agency. “The Way,” is trust. The God of Israel is fidelity. The proclamation is clear: return to trust, restore covenantal agency, and stand on the table with weight, not with words.