Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

To those who doubt me….

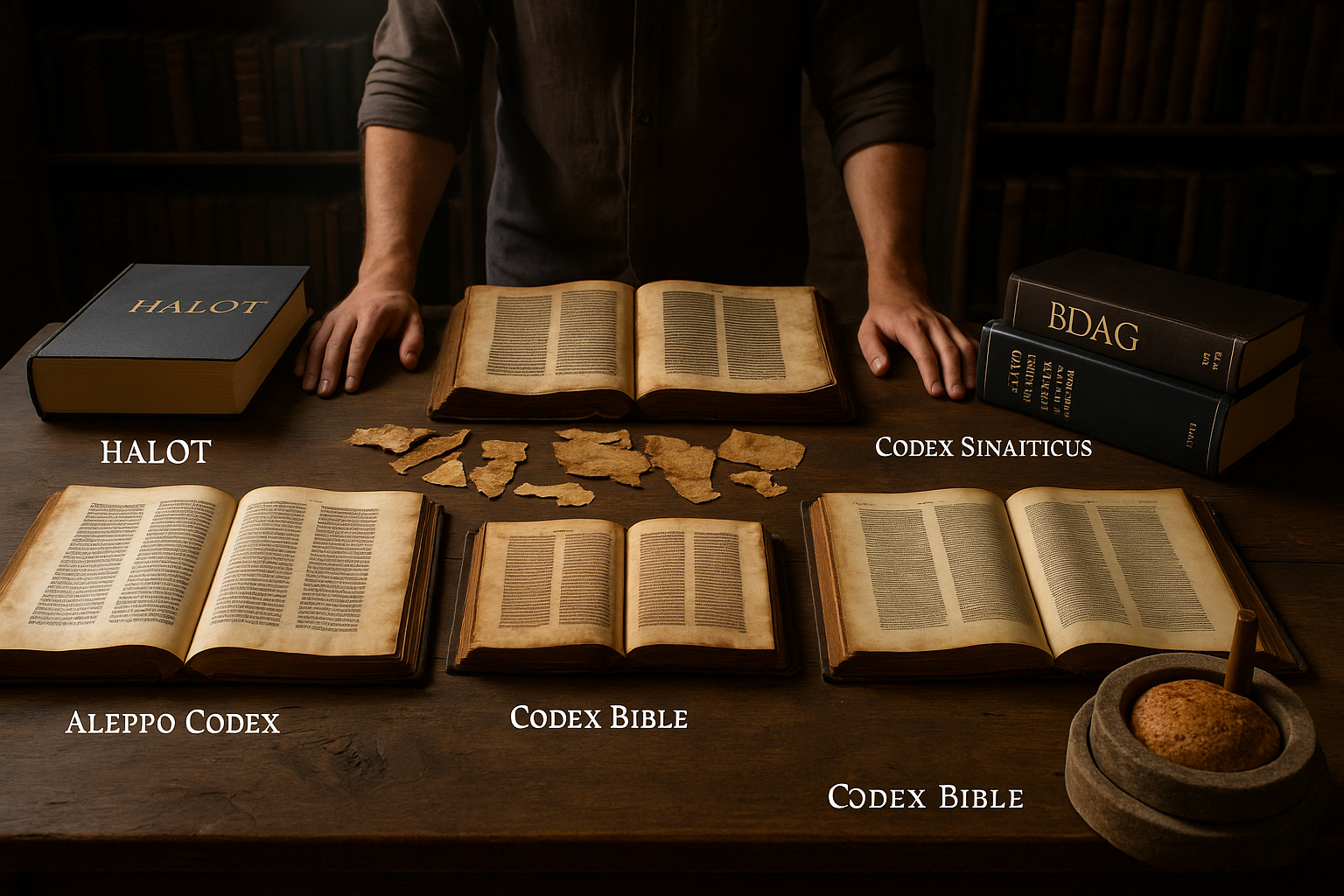

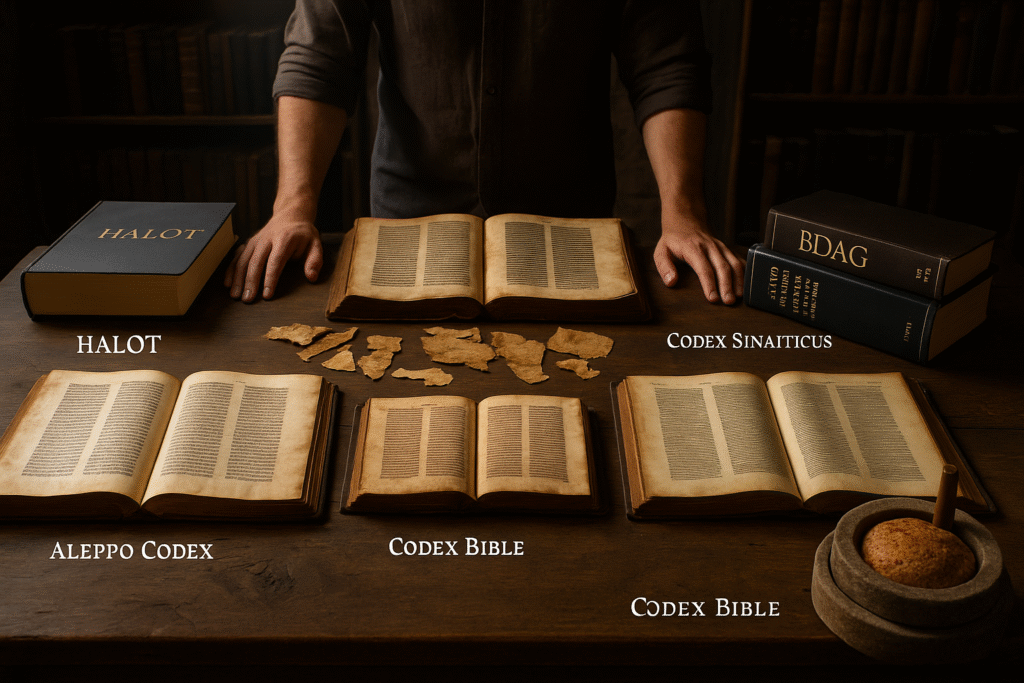

People love to throw out the line, “Well, you’re not a scholar, what do you know?” as if the truth somehow hides behind a degree or a title. The reality is this: the truth doesn’t need a collar, a gown, or a plaque on the wall. The truth just needs to be handled faithfully. And while I don’t carry the stamp of an academic guild, I carry something that cuts deeper — access to the same manuscripts, the same lexicons, and the same tools the scholars use, and the conviction to actually let the Word speak instead of bending it to fit tradition. That’s what this is about. Not blind trust in English Bibles, not parroting church clichés, but anchoring myself directly to the sources that outlast titles, councils, and institutions. So let’s talk about the tools I use, and then tell me again I don’t know what I’m holding.

First, the Hebrew Scriptures, what most call the Old Testament, though I’ll call it what it really is — the Tanakh. At the heart of my foundation is the Aleppo Codex, dating back to around 930 CE. This is not some random old scroll; it is the crown jewel of the Masoretes, the scribes who made it their life’s obsession to preserve the text down to the last letter. They didn’t just copy words; they counted letters, marked vowels, and built a system of checks so precise that modern computer algorithms pale in comparison. That’s what Aleppo represents — accuracy born of reverence. Yes, it’s incomplete, thanks to riots in 1947 that destroyed much of the Torah. But here’s the thing: incomplete doesn’t mean unreliable. The Leningrad Codex, written in 1008 CE, steps in where Aleppo is missing. It’s not some stranger; it’s Aleppo’s sibling, born from the exact same Ben Asher Masoretic tradition. The two fit together like bone and marrow. And if you want to go further back than the Masoretes, the Dead Sea Scrolls, fragments from as early as 200 BCE, show that what Aleppo and Leningrad preserve is no accident — it is the same stream of text flowing through time. So when someone asks, “Where do you get your Hebrew from?” the answer isn’t “some English Bible.” It’s Aleppo, Leningrad, and the Dead Sea Scrolls. Tell me again I don’t know what I’m working with.

Now, let’s step over into the Greek. If you want to talk New Testament, or even the Septuagint, the Greek Old Testament, you don’t start with King James, you don’t start with NIV, you don’t even start with Erasmus and his patched-together Textus Receptus. You go straight to the heavyweights: Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus. Both from the early fourth century, around 325 to 360 CE. Both nearly complete. Both untouched by a thousand years of later church editing. Codex Sinaiticus was found at St. Catherine’s Monastery at Sinai, and it contains almost the whole Bible in Greek. Codex Vaticanus has been sitting in the Vatican Library for centuries, just as ancient, just as reliable. Where the two agree, the debate is over. Together, they form the backbone of every serious text-critical study of the New Testament. You want to know what the earliest Greek-speaking assemblies read? You look here, not at some English preacher’s notes. And that’s exactly what I do.

Of course, manuscripts are only half the battle. You can hold Aleppo and Sinaiticus in your hands, but if you can’t read the language, you’re still blind. That’s where the real tools come in. For Hebrew and Aramaic, I use HALOT — The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. This isn’t some devotional word list with cherry-picked glosses. HALOT is the most comprehensive modern lexicon in existence. It draws from the Masoretic text, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Septuagint, and gives you the full semantic range of every word. Want an example? The Hebrew word zakar. English Bibles flatten it into “male.” HALOT shows you it’s not that simple. It’s an anatomical male without built-in social or covenantal status — a nuance that changes entire interpretations of key passages. Or take chesed, which English scribbles down as “love” or “mercy.” HALOT unpacks it as covenant loyalty, steadfast commitment, relational fidelity. That’s the difference between hand-me-down translations and going to the source. One keeps you in chains; the other opens the vault.

Then comes Greek, and the undisputed tool here is BDAG, the Bauer-Danker-Arndt-Gingrich Lexicon. This is the gold standard, period. BDAG doesn’t just hand you a word-for-word gloss. It takes you into the actual world of first-century Greek. It draws from the New Testament, yes, but also from Jewish writings, papyri, inscriptions, and early Christian literature. It tells you how people actually used the words in their letters, contracts, and prayers. Take dikaiosynē. English gives you “righteousness” and calls it a day. BDAG shows you that in context it can mean justice, covenant alignment, relational loyalty, or uprightness, depending on how it’s used. Suddenly, Paul’s letters stop sounding like abstract theology and start sounding like real covenantal arguments in real time. That’s the kind of clarity BDAG brings.

HALOT and BDAG together are a powerhouse. They don’t care about your denomination, they don’t care about your doctrine, and they don’t care about defending your tradition. They care about language. They care about what Hebrew and Greek actually said before theology got its hands on it. That’s why I use them. They anchor me in the raw Word before anyone flattened it into English slogans. And they are the exact same tools the universities and the so-called scholars use. So no, I’m not pulling this out of thin air. I’m standing on the same ground they are, I’ve just stripped away the ivory tower and the gatekeeping.

So here’s my framework, laid bare: Aleppo and Leningrad for Hebrew, Sinaiticus and Vaticanus for Greek, HALOT and BDAG for translation, with the Dead Sea Scrolls as the ancient witness confirming the whole line. That’s not opinion; that’s the backbone of textual faithfulness. You can question me all you want, but you can’t question the fact that these are the oldest, most reliable, and most universally respected sources and tools we have. This is not a hobby. This is not me playing games. This is me refusing to let betrayal have the final word. If the English Bible is processed bread, then this is the grain itself, crushed, sifted, and baked fresh. It takes more effort, it takes more time, and it takes more fight, but it means when I open my mouth, I know I am not echoing tradition — I am letting the Word itself breathe. And if that’s not scholarship, then scholarship has lost its meaning.