Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

If the Shoe fits……

Let’s start by clearing the fog around a few words that people often use loosely, because the looseness itself becomes a hiding place. An opinion is a judgment—often provisional—about what is true or good. At its healthiest, an opinion is open to evidence, aware of its own limits, and willing to change when reality contradicts it. At its unhealthiest, an opinion hardens into identity armor: I am my take. That’s where motivated reasoning kicks in, where facts are sifted by whether they protect the self rather than whether they reflect the world. In practice, this means an opinion “works” like a filter: it selects what confirms the self and rejects what corrects the self. The more public the opinion, the more ego gets welded to it, and the harder it becomes to revise.

Influence is the power to tilt other people’s perception, emotion, and behavior. It “works” through a handful of dependable human levers: social proof (if many believe it, it must be right), authority (if someone high-status says it, it must be right), repetition (if I hear it often, it feels true), and identity signaling (if my group says it, I’ll say it too). Technology turbocharges these levers: algorithms reward engagement, and nothing engages like outrage. So influence isn’t neutral; it compounds. A message doesn’t simply reach more people; it reshapes what seems normal to more people. That’s why those with large platforms don’t merely express; they set the temperature in the room.

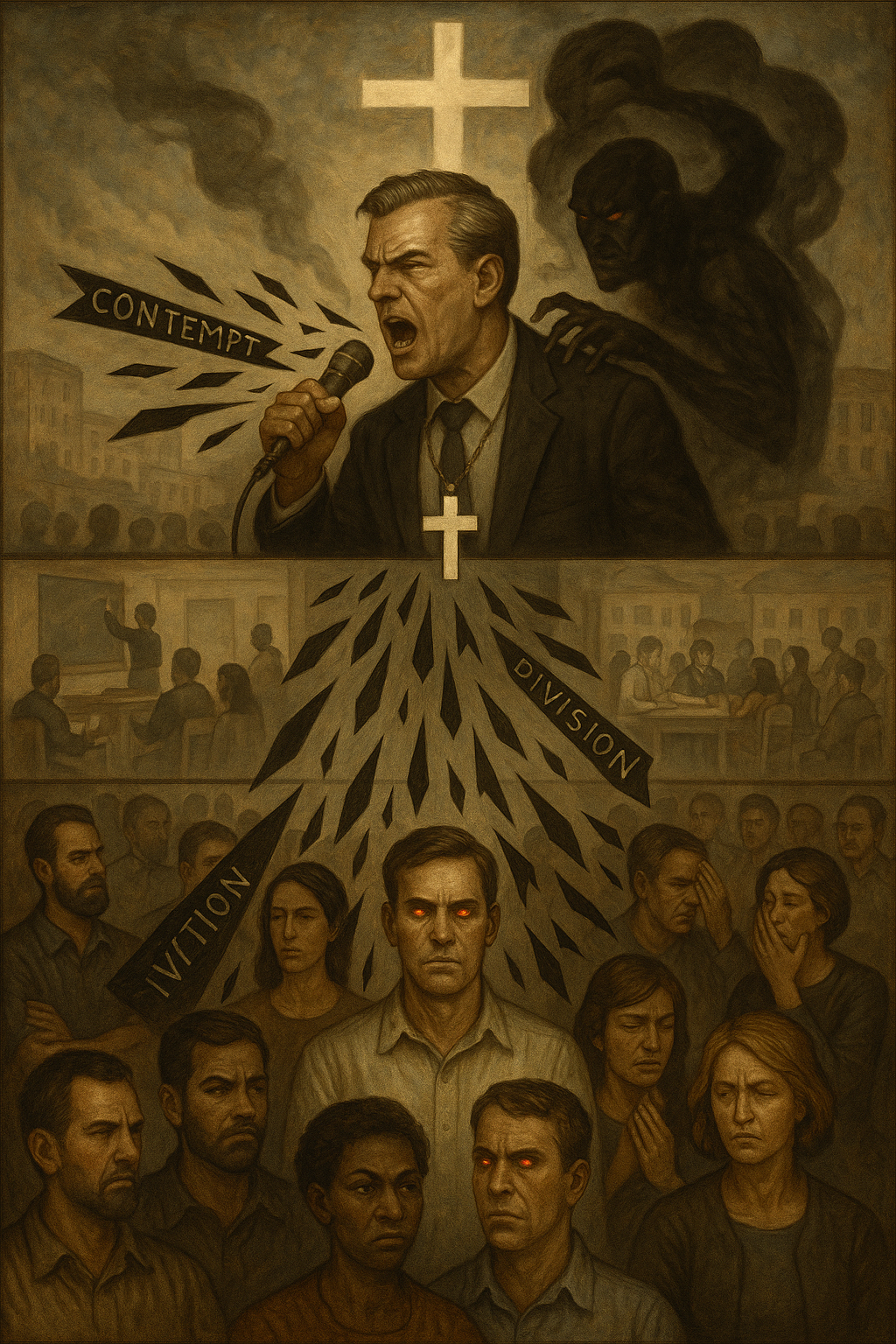

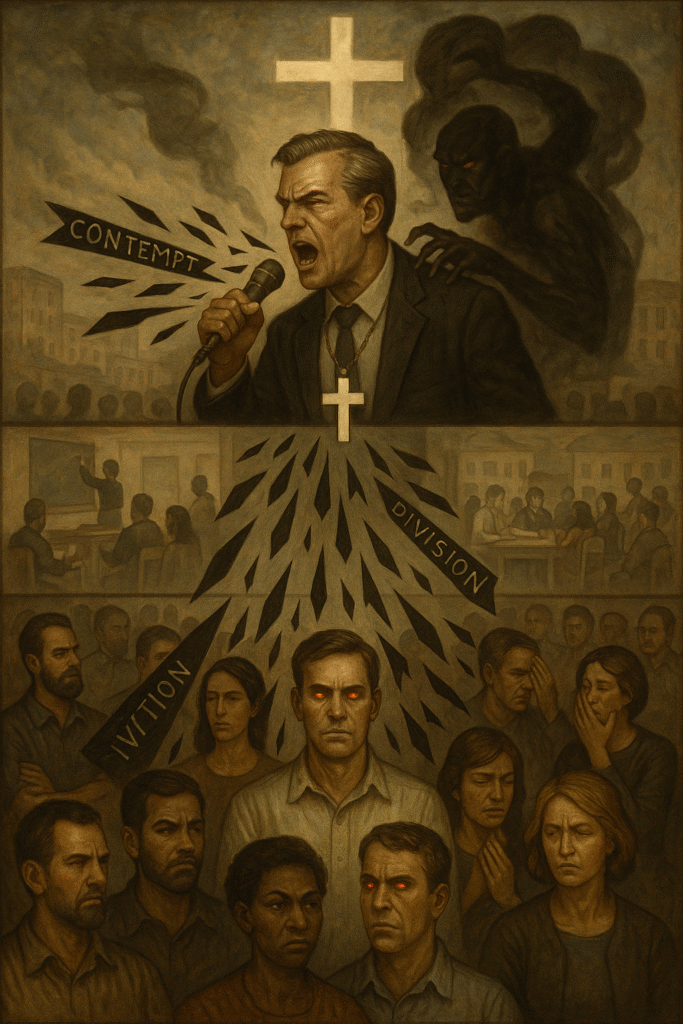

Hate speech is speech that targets a person or group for who they are—race, ethnicity, religion, sex, gender, orientation, disability, or other core identity—and frames them as less than, dangerous, impure, or unworthy of equal concern. It “works” first by dehumanizing (naming someone as a type instead of a person), then by normalizing (turning contempt into a social cue), and then by licensing (signaling that mistreatment is allowed or even righteous). Even when it avoids slurs and hides behind sarcasm, dog whistles, or “just asking questions,” the function is the same: to draw a bright circle around “us,” shove “them” outside of it, and make harm feel permissible. Over time, this shifts the Overton window—what is sayable today becomes doable tomorrow.

Evil, in the everyday sense, is the will to harm while knowing better, or the will to treat people as objects to be used rather than neighbors to be loved. It “works” by recruiting ordinary faculties—reason, loyalty, humor, ambition—and bending them off-axis. It rarely arrives as a cartoon villain; it arrives as a bargain: keep your status, your comfort, your belonging, and pay with someone else’s dignity. Mechanically, evil advances through rationalization (“I’m just telling hard truths”), diffusion of responsibility (“everyone’s saying it”), and desensitization (today’s shock becomes tomorrow’s shrug). Spiritually, it seeks agreement; it wants consent. The door it knocks on is always the will.

Now take those definitions and scale them to a career built on hate with massive influence. The business model is the outrage economy: provoke → trend → monetize → escalate. The product is attention; the fuel is indignation; the brand is defiance. The tactics are well-worn—selective anecdotes that smear whole groups, humor that punches down but claims immunity as “just jokes,” data-looking charts without context, euphemisms for cruelty, and a steady drip of “I’m only saying what you’re afraid to say.” Plausible deniability becomes a shield: “I never told anyone to harass,” even as the audience is trained to take the hint. The result is not a debate; it’s an assembly line that manufactures permission.

The trickle-down effect is real because norms are infectious. When a high-visibility figure frames contempt as courage, local imitators copy the posture. Group chats, comment sections, classrooms, and break rooms begin to echo the tone. Targets feel smaller; bystanders feel quieter; the eager find a banner to gather under. Offline consequences follow: bullying, lost opportunities, discriminatory gatekeeping, threats, occasional violence, and a chilling effect on anyone who might have spoken up. Policy can shift too, because stories repeated with confidence become “common sense,” and common sense is what legislatures codify.

What makes this truly dangerous is the willfulness it cultivates. People align with harmful projection not only because they are misinformed, but because it pays them back—belonging, clarity, status, a simple map of good guys and bad guys. Once the alignment is part of identity, correction feels like attack, and repentance feels like defeat. Yet responsibility doesn’t evaporate in a crowd. There is a moral gradient—from the architect who crafts the message, to the amplifier who spreads it, to the applauder who rewards it—but everyone on the chain is feeding the same fire. Evil requires a willing host; it doesn’t create hands, it borrows them. It doesn’t invent voices, it tunes them. It thrives where resentment is nursed, where fear is stroked, where pride refuses to be taught.

This is why the hypocrisy of wearing the name “Christian” while embodying these patterns is so stark. The Messiah commands love of neighbor and enemy, truth without malice, speech that gives grace, and a fruit that looks like humility, patience, and self-control. To baptize contempt as courage, to market dehumanization as discernment, to wield scripture as a cudgel for domination while ignoring its call to service—this is mask-work, not discipleship. It is zeal without knowledge, heat without light. The test is simple and ancient: does your speech lift the image of God in the other, or does it tear it down? If it tears it down, the label you wear cannot launder the harm you do.

So the line between not understanding and not choosing to understand becomes visible. When terms are defined and mechanisms are laid bare, what remains is a decision: to keep opinions open to truth or to fuse them to ego; to use influence to dignify or to demean; to refuse speech that dehumanizes or to harvest it for profit; to close the door on evil’s bargain or to sign it with your silence and your shares; to let the name you claim shape your words, or to use that name as a costume while you play a different part. The path out of cognitive dissonance is costly but clear—tell the truth even when it shrinks your audience, honor people even when it complicates your narrative, and choose the difficult work of understanding over the cheap thrill of being right.