Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

A message to Believers….and the Skeptic.

Introduction: The Battlefield of Belief

In the never-ending clash between the believer and the skeptic, few battlegrounds are as hotly contested—or as frequently misunderstood—as the reliability of the New Testament manuscripts. This isn’t just a debate about parchment or papyrus—it’s a war over the foundation of Christian faith itself.

The skeptic enters the arena armed with a familiar arsenal: “We don’t have the originals.” “The copies are late.” “The manuscripts are riddled with variants.” And most devastatingly, “They’re all just fragments.”

To the untrained ear, this sounds damning.

But what if the very thing that sounds like a weakness—the fragmented state of the manuscripts—is actually the reason we can trust the text?

Enter the apologists. These aren’t YouTube theologians or pulpit performers. These are historians, textual critics, linguists, and philosophers—men and women with Ph.Ds, ancient language fluency, and deep familiarity with dusty libraries and digital scans. These are warriors armed not with slogans, but with fragments of truth that tell a unified, divinely preserved story.

This deep dive is about what those fragments reveal. About the minds who have pieced them together. And about the overwhelming evidence that the message of Jesus Christ has not been lost in time—it has been guarded by time itself.

Imagine the text of the New Testament like a priceless ancient mosaic that shattered over time. Some pieces were chipped, some misplaced, and others faded—but thousands of these tiles remain. And through painstaking work by textual archaeologists, that image has not only been reassembled, it has been sharpened. In fact, it is precisely because the pieces are so numerous and independently preserved that the image remains so clear.

The Manuscript Advantage: Why Quantity Crushes Skepticism

This figure alone places the New Testament in a league of its own. No other ancient document even comes close. Most of what we know from antiquity—Plato’s dialogues, Caesar’s commentaries, or Aristotle’s treatises—comes from fewer than 20 extant manuscripts, often separated from the originals by a millennium or more. The New Testament, by contrast, offers 5,800+ Greek manuscripts, many of which date to the early centuries of the Church, allowing for layered comparison across both time and geography. The Greek manuscripts are especially significant because they reflect the original language in which the New Testament was written. This gives scholars a robust data set from which to perform textual criticism and trace the fidelity of transmission. To have that much Greek documentation is not a luxury—it’s a historical anomaly. It tells us the early Church didn’t just write the Gospel—they guarded it.

Imagine having thousands of copies of a handwritten letter spread across different regions, with some missing words, others with smudges, and a few with coffee stains—but all overlapping in content. When pieced together, they don’t create chaos—they create clarity. It’s like having a hundred blurry photographs of the same person from different angles: none of them perfect, but together, they reveal the unmistakable features of the original. The imperfections do not distort the image—they define its edges with even greater accuracy.

Here’s where the scope becomes truly global. The gospel was not a message whispered in one place—it was shouted across continents, and the written record reflects that. Translations in Syriac (spoken in ancient Mesopotamia), Coptic (used in Egypt), Armenian, Ethiopic, Georgian, and Latin exploded throughout the 2nd to 5th centuries, making the New Testament one of the most linguistically translated documents in history. Why is this important? Because even if all the Greek manuscripts were destroyed, we could reconstruct the entire New Testament by reverse-engineering from the early translations and their cross-referenced quotes in patristic writings. The multilingual spread acts like a backup system across space and time—a divine redundancy encoded into church history. These versions didn’t drift from the original; they anchored it in new lands and new hearts.

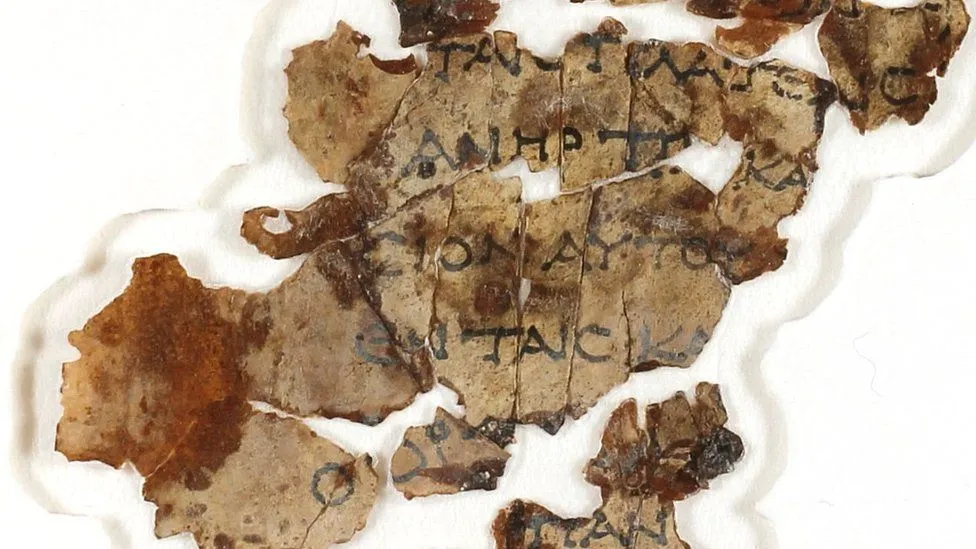

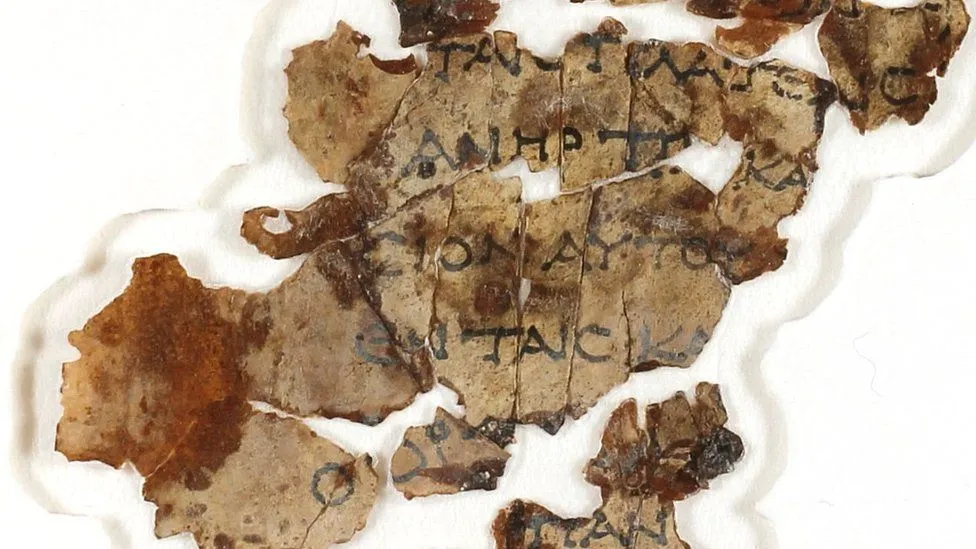

Let this sink in: P52 (the John Rylands Fragment), dated between AD 125–135, was copied within living memory of the apostle John. Most ancient authors don’t have manuscripts until 500–1,000 years after their deaths. Yet the New Testament has first- and second-century manuscript support, which, in manuscript terms, is like holding a photograph of the original. And this fragment wasn’t found in Israel or Rome—it was found in Egypt, which means the Gospel of John had already traveled across cultural and geographical barriers within a few decades. It testifies to early, rapid transmission and points to widespread circulation rather than localized legend-building. This utterly wrecks the claim that the gospels were invented later. No myth or political agenda could move this fast and get this far without being caught in its own contradictions.

This is the deathblow to the ‘corruption’ narrative. If scribes had conspired to change the Bible, their changes would appear uniformly across the manuscripts. But that’s not what we find. Instead, we see manuscripts from Alexandria, Antioch, Byzantium, Carthage, and Gaul, each reflecting slight scribal differences—but all telling the same essential story. This geographical spread means that no single authority could control the text. No Roman bishop, emperor, or theological clique could have rewritten the Bible without being contradicted by manuscripts already dispersed. That’s the beauty of multiplicity—it serves as a textual immune system against tampering. Even if a scribe added a marginal note or misspelled a name, thousands of other copies preserve the original. The errors don’t hide the truth—they highlight it through contrast.

This is where the science of textual criticism shines. Think of every manuscript fragment as a puzzle piece—not from one puzzle, but from many printings of the same puzzle. Even if one piece is burned, faded, or torn, scholars can align the edges with other pieces to reconstruct what was lost. This is called textual triangulation, and it works best when you have overlapping, widespread data. And guess what? The New Testament has more textual data than any document from antiquity. Scholars don’t guess what the New Testament says. They compare manuscripts like forensic investigators at a crime scene, building a clear picture from partial prints. If five fragments agree and one doesn’t, it’s not confusing—it’s revealing. That outlier gets exposed and dismissed, while the consensus remains. That’s why we can know what the original said with such high confidence.

It’s like having multiple eyewitnesses describe the same event. One says the car was red, another says it was a convertible, and another remembers the license plate—but taken together, you don’t get confusion, you get confirmation. The diversity of detail reconstructs the total picture.

This is the poetic paradox of Scripture’s preservation: God didn’t need perfection to prove truth. He used imperfection to reveal reliability. Rather than one pristine scroll locked in a vault, we have thousands of worn, copied, handed-down manuscripts—touched by human hands, yes, but preserved by divine providence. These weren’t copied by computers; they were transcribed by persecuted believers, monks, and scholars who believed they were handling holy words. And in their copying—yes, even in their mistakes—they gave us a system of verification more effective than any single source could offer. Imagine trying to lie when 25,000 eyewitnesses are standing behind you. The manuscript tradition is not a weakness. It’s the most transparent and trustworthy textual legacy in all of literature.

This is the part where facts meet fire. At some point, skepticism ceases to be critical thinking and becomes willful blindness. The data is there. The fragments are there. The scholarship is there. The question is no longer “Is the New Testament reliable?” It’s “What’s keeping you from admitting it?” Denying the reconstructability of the New Testament in the face of such overwhelming evidence isn’t honest doubt—it’s selective disbelief. This isn’t a matter of having too little evidence. It’s a matter of having too much to ignore. And to continue ignoring it isn’t neutral—it’s negligent.

The Defenders of the Text: Expanded Profiles of the Key Apologists

Wesley Huff – The Clear-Eyed Canadian

Wes Huff speaks with the clarity of a preacher and the precision of a scholar. His background in religious studies and his current doctoral research into manuscript transmission equip him to speak fluently in both academic and faith-based circles. What makes Huff so compelling is his refusal to dodge the hard questions. He agrees with the skeptic that variants exist. He acknowledges the fragments. But then he points to the methodology of textual criticism, where redundancy and distribution give scholars a high degree of confidence in original readings. Wes Huff doesn’t appeal to blind faith. He appeals to real evidence, showing that no other ancient document—not Plato, not Caesar, not Homer—comes even close to the manuscript wealth of the New Testament.

Dr. Daniel Wallace – The Archivist of Apostolic Ink

Founder of the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts, Daniel Wallace has traveled the world, personally examining and digitizing thousands of ancient texts. He’s not just theorizing—he’s preserving the actual ink of the early church. Wallace’s brilliance lies in textual triangulation: the ability to compare manuscripts from different families (Alexandrian, Byzantine, Western) and spot anomalies, forgeries, or accidental alterations. And after decades of doing this at the highest academic levels, Wallace confidently declares: “We can reconstruct the original New Testament with over 99% certainty.”

Craig A. Evans – The Archaeologist of Authenticity

Dr. Craig Evans brings a shovel to the fight—literally. As a specialist in ancient texts and archaeology, Evans uses physical evidence (such as ossuaries, burial practices, inscriptions, and the Dead Sea Scrolls) to show that the New Testament is rooted in real places, real names, and real timelines. He famously said, “The Gospels smell like the first century.” That’s because they do. Evans demonstrates that the people, cities, coins, and customs described in the NT align with known historical data—making late invention or fabrication virtually impossible.

Peter J. Williams – The Detail-Driven Defender

At Tyndale House in Cambridge, Dr. Peter Williams oversees one of the most respected biblical research centers on Earth. In his book Can We Trust the Gospels?, he walks readers through name frequencies, geographic familiarity, and linguistic patterns that would be impossible for forgers to fabricate centuries later. For example, the Gospel authors get even obscure village names right—places only a local would know. He calls this “undesigned coincidence,” where multiple Gospel accounts independently confirm details in ways too natural to be coordinated.

Michael J. Kruger – The Canon Watchman

Kruger specializes in the history and development of the canon—the process by which certain books were recognized as authoritative. His research dismantles the false notion that the New Testament was politically curated at the Council of Nicaea like some ecclesiastical talent show. Instead, he proves that the core of the New Testament canon was already in circulation, copied, and treated as authoritative long before Nicaea. His work demonstrates that early Christians knew what belonged in the New Testament—not by fiat, but by apostolic origin, widespread use, and theological harmony.

The Skeptic’s Wild Card: Bart Ehrman – Judas in a Robe of Academia

Bart Ehrman is a paradox. He is a New Testament scholar. He is a former evangelical turned agnostic. He writes bestsellers that cast doubt on the Bible—books like Misquoting Jesus and Jesus, Interrupted. But here’s the twist: Ehrman’s conclusions don’t match his data. Ehrman admits in debates, books, and lectures that:

“The essential Christian beliefs are not affected by textual variants in the manuscript tradition of the New Testament.”

That’s right. The most well-known critic of the Bible admits that none of the variants affect core Christian doctrine. That’s like Richard Dawkins confessing that Genesis might be historically reliable on page 284 of a book titled Why God Is Dead. So why the dramatic framing? Because Ehrman’s beef isn’t textual—it’s theological. He believes the Bible contradicts itself in meaning, not in transmission. But even so, his acknowledgment that the manuscripts preserve doctrine is a devastating blow to his own fans who think the Bible was rewritten like a game of telephone.

Conclusion: Reconstructing the Faith from the Dust

The New Testament hasn’t just survived history—it’s been verified by it. Through thousands of fragments, spread across continents and centuries, a unified message emerges: Jesus of Nazareth lived, taught, died, and rose again. And that message was so vital, so transformative, that it was copied again and again, even under threat of death, across language barriers and empires. We don’t need one flawless manuscript—we have thousands of imperfect ones that, when combined, create a picture more trustworthy than any other ancient document.

To deny this is not academic integrity. It’s intellectual negligence.

So the next time someone smirks and says, “But aren’t they all just fragments?”—lean in, smile, and say:

Yes. Beautiful, powerful, truth-confirming fragments.

And together, they form a testimony that time couldn’t bury, and doubt couldn’t erase.