Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

To Whom it may concern…..

There is a reason the word gods echoes so loudly in the modern ear while sounding so different in the voice of Scripture: translation has flattened what the Hebrew and Greek kept multi-layered. The viral claim that the Bible acknowledges literal rival deities is not a recovery of ancient insight; it is a modern confusion that mistakes vocabulary for ontology and hears plurality where the text asserts singularity. The Bible’s monotheism is not shy, tentative, or late. It is thundered from Sinai, prayed in Israel’s daily confession, proclaimed by the prophets, and explained by the apostles. The Scriptures do not put Yahweh at the top of a pantheon; they leave Him alone on the field. Everything else that people call god—whether carved, conjured, crowned, or culturally inherited—is exposed as an idol, a spirit, a ruler, or a human authority, never a deity in essence or being. Think of counterfeit currency: many bills may circulate, and they may even buy a few moments of attention, but the existence of counterfeits does not multiply the number of treasuries. The reality of the one true Treasury is precisely what makes a counterfeit recognizable. So it is with Yahweh and every so-called god.

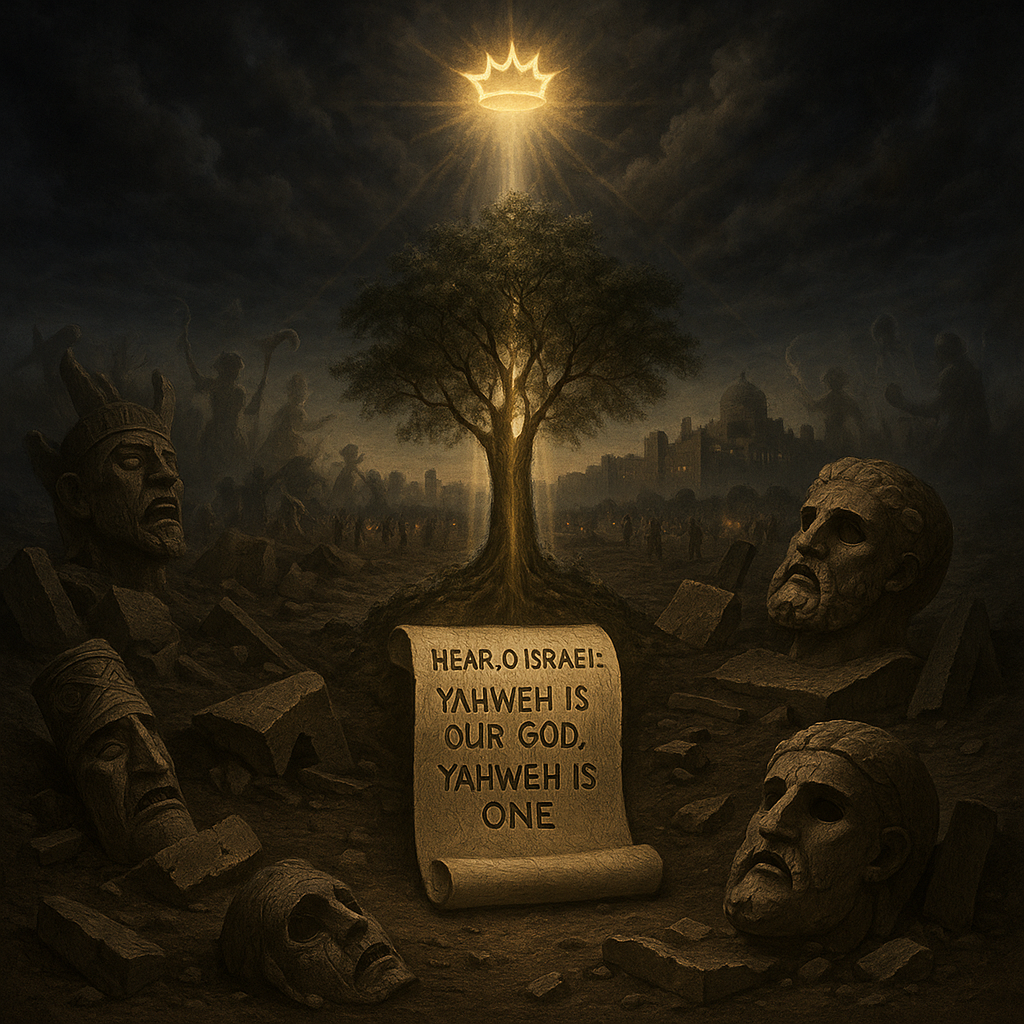

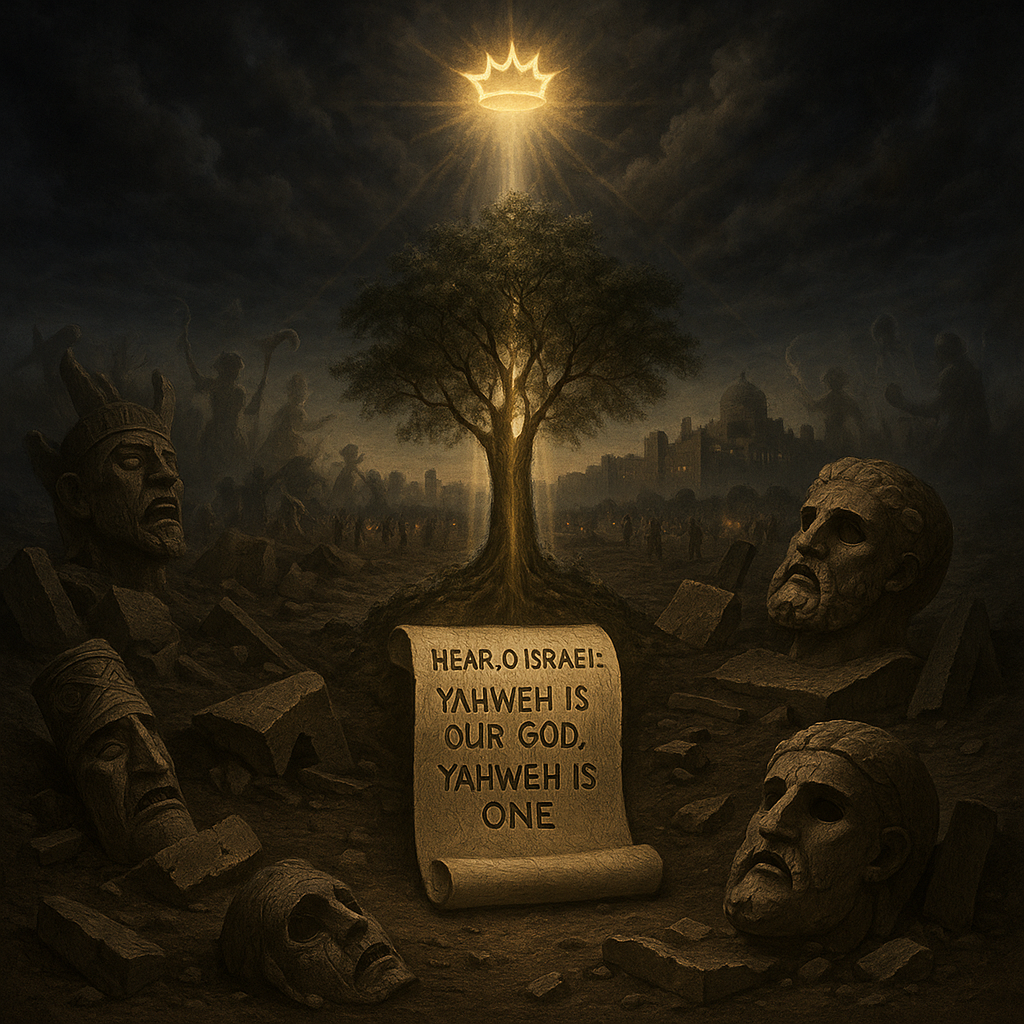

If we start where Israel always starts, monotheism is not a dictionary entry but a confession. Hear, O Israel: Yahweh our God, Yahweh is one (Deuteronomy 6:4). That one sentence frames the whole biblical cosmos. Isaiah restates it under oath of prophecy: I am Yahweh, and there is no other; besides Me there is no God (Isaiah 45:5). The New Testament does not relax this claim; it repeats it in Gentile cities soaked in idols: we know that there is no God but one (1 Corinthians 8:4). Monotheism, then, is not “one chief among many” (that would be henotheism); it is the claim that only one truly divine being exists and all alleged rivals are nothing. A lighthouse does not compete with the fog; it negates it. The light does not enter a contest with shadows; it simply exposes them as the absence of light. This is the tone of biblical monotheism.

The language of the Bible reinforces this confession in a way English often obscures. In Hebrew, the most common term for God or gods is elohim. The form is plural, but when used for Yahweh it functions as a majestic singular, and when used for others it denotes beings or authorities treated as mighty ones. Thus the first commandment reads, you shall have no other elohim before Me (Exodus 20:3). The psalmist can say, Yahweh is a great king above all elohim (Psalm 95:3), and immediately strip those elohim of any claim to deity: all the elohim of the peoples are idols, but Yahweh made the heavens (Psalm 96:4–5). The singular forms el and eloah appear as well—For I am El, and there is no other; I am Elohim, and there is none like Me (Isaiah 46:9)—tightening the focus on God’s uniqueness. None of these usages suggest rival, equally divine beings. Rather, they acknowledge that humans ascribe divine weight to many things and persons; Scripture grants the vocabulary of devotion without granting the ontology of deity.

When the writers want to unmask the costume, they change terms. Idols are called atsabbim—things fashioned, shaped, worked by human hands (Psalm 115:4). When the mask slips further, the text names the spiritual reality behind the shrine: shedim—demons, not divine equals (Deuteronomy 32:17; Psalm 106:37). Judges and rulers can even be called elohim in a functional sense—authorities vested with weight—which is why discernment about context is essential (e.g., Psalm 82). The point is consistent: people pour reverence into objects, offices, or spirits until those things function as gods in their lives; the Bible will call them elohim to describe that misplaced status while denying they possess divinity in essence. It is the difference between a crown on a head and the head that gives a crown meaning. Swap heads all you like; you will never create a second life.

The Greek of the Septuagint and the New Testament keeps the distinction just as sharply. Theos is the standard term for God, used for the one true God and for what people call gods. But the moment the apostles wish to evaluate the claim, they reach for precise language: eidolon (idol, image, phantom) to emphasize emptiness, and daimonion for the spirits behind the cults (1 Corinthians 10:19–21). Paul can stand in Athens, a forest of altars and statues, and say that the divine being is not like gold or silver or stone, an image formed by the art and imagination of man (Acts 17:29), while also teaching the Corinthians that sacrifices to idols are sacrifices to demons and not to God (1 Corinthians 10:20). The apostolic verdict is surgical: an idol is nothing in the world, and there is no God but one (1 Corinthians 8:4), yet idolatry is spiritually dangerous because deceiving spirits weaponize human devotion.

Read the canon straight and the witness is uniform. No other elohim before Me (Exodus 20:3). You shall not follow other elohim, any of the elohim of the peoples who surround you (Deuteronomy 6:14). Yahweh is great and greatly to be praised; He is to be feared above all elohim… for all the elohim of the peoples are idols, but Yahweh made the heavens (Psalm 96:4–5). For You, Yahweh, are Most High over all the earth; You are exalted far above all elohim (Psalm 97:9). Thus says Yahweh… I am the first and I am the last; besides Me there is no elohim (Isaiah 44:6). I am Yahweh, and there is no other; besides Me there is no God (Isaiah 45:5). Jeremiah sneers at the claims of the nations: the gods who did not make the heavens and the earth shall perish from the earth and from under the heavens (Jeremiah 10:11). The Bible does not wobble here. It uses the wide word to describe the human phenomenon, then narrows the meaning to assert the divine reality. The ocean of claims does not create a second shore.

What, then, is idolatry? It is functional godhood assigned by human worship. No one truly worships what they deem beneath them; worship presupposes elevation. When the human heart magnifies a thing—stone, spirit, nation, appetite—until it commands devotion, that thing becomes, functionally, a god in that person’s world. Romans 1 describes the exchange with chilling clarity: they exchanged the glory of the incorruptible God for an image… and exchanged the truth of God for a lie, and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator (Romans 1:23–25). That exchange does not upgrade the creature into deity; it downgrades the worshiper into slavery. Consider Dagon toppling before the ark (1 Samuel 5): a carved image cannot stand where the presence of Yahweh enters. Consider Carmel: Baal’s prophets cry and cut themselves, but there is no voice, no one answers; then Yahweh answers by fire and consumes the offering and the water and the stones (1 Kings 18). Consider the golden image in Babylon: kings can heat furnaces seven times over and still fail to generate a god (Daniel 3). Idolatry is like building a throne for a shadow and calling it a king; at noon the throne is empty, and at dusk the room is dark.

History confirms what Scripture declares. Civilizations stacked altars to names now found mainly in museums and myth compendia. In the ancient Near East, Baal, Molech, and Asherah demanded offerings and enacted fertility dramas; in Egypt, Ra, Osiris, and Isis were woven into the state’s very identity; in Babylon, Marduk and Ishtar presided over empire and conquest; in Greece, Zeus, Apollo, Athena, and the civic cults choreographed festivals and law; in Rome, Jupiter, Mars, and Venus shared space with imperial genius worship; in the north, Odin, Thor, and Freyja thundered through sagas; across the earth Indigenous and tribal peoples revered nature deities, animal spirits, ancestor veneration, Dreamtime beings, Polynesian creators like Tāne and Tangaroa, and a thousand localized pantheons; in the Amazon, shamans mediated forest spirits; in Africa, lineages enshrined the honored dead and regional powers; on the plains and mesas of the Americas, ceremonies bound community to sky, earth, and buffalo. The common thread is unmistakable: humanity elevating creation, ancestors, rulers, and spirits into the status of gods, projecting divine weight onto what is not divine. The patterns vary by geography, but the mechanism is identical—devotion confers a title the object cannot ontologically bear.

Now set that universal phenomenon beside one thing that is not universal: Israel. Yahweh did not merely proclaim Himself in a book and leave the rest to memory; He tied His name to a people, a land, a history, and a future that could be weighed and watched. He called Abram with a promise: I will make you a great nation… and in you all the families of the earth will be blessed (Genesis 12:1–3). He warned of exile and promised regathering: then Yahweh your God will restore you from captivity… and will gather you again from all the peoples… and will bring you into the land which your fathers possessed (Deuteronomy 30:3–5). He swore by the fixed order of sun, moon, and stars that Israel would not cease from being a nation before Him (Jeremiah 31:35–37). He painted resurrection in Ezekiel’s valley and reunification on the mountains of Israel (Ezekiel 37). He spoke of a second great ingathering from the four corners of the earth (Isaiah 11:11–12). The prophets do not merely offer pious hopes; they lay down testable claims that run like a thread from antiquity into the present. Israel is not a mythic pantheon’s collapsed cult; it is a living nation whose existence, scattering, preservation, and re-gathering form a continuous, observable storyline. If you want a kind of scientific test—an empirical control in the realm of history—this is it: which god left a measurable prophetic trail that you can still touch? The answer is not Zeus, not Ra, not Odin, not the nameless spirits of grove and river. The answer is Yahweh, stamped across a people who stubbornly persist because His word does.

This contrast does not demean the sincerity of Indigenous traditions or the beauty of cultural memory; it simply recognizes the difference between a human pattern and a divine signature. Human religion tends to project reverence upward onto what is near—sun and storm, ancestor and animal, king and crop—like trying to navigate the night by campfire sparks. The biblical claim is that Yahweh lights the heavens themselves and fixes the stars in their courses; His word speaks, and the world endures; His promises shape history, and the nations witness it. If an idol is a mirror that throws your own gaze back at you, Israel is a window you can look through and see the faithfulness of the One who stands behind it.

This is why the rhetoric that “the Hebrew Bible admits other gods” is not only incorrect but spiritually perilous. It invites seekers to chase phantoms as if they were peers of the Almighty, to treat shadows as if they could cast light. The Torah forbids that pursuit at the root: do not follow other elohim (Deuteronomy 6:14); do not turn and serve them (Deuteronomy 11:16); do not even name them in oaths (Joshua 23:7). The prophets brand them as nothings that will perish (Jeremiah 10:11), and the psalmists mock their impotence (Psalm 115:4–8). The apostles warn that behind the wood and stone lurk deceiving spirits (1 Corinthians 10:20; 1 Timothy 4:1), and they plead with former idolaters: when you did not know God, you were enslaved to those that by nature are not gods (Galatians 4:8). Saying “other gods exist” does not honor ancient nuance; it repeats the oldest lie in a new accent. It is the theological equivalent of sailing by a painted compass—every degree you travel in that direction takes you farther from harbor.

Gather the threads and the tapestry is clear. The Scriptures are consistently, aggressively monotheistic. Their principal terms—elohim in the Hebrew Bible and theos in the Greek—describe both the true God and what people treat as gods, but the canon refuses to grant ontological parity to anything creaturely. When the text wants to name the impostor, it reaches for words like atsabbim and eidolon to stress emptiness; when it wants to name the power behind the shrine, it says shedim and daimonia; when it wants to describe weighty human offices, it may still say elohim, but never to blur the Creator-creature line. The Bible’s argument is not that Yahweh outranks competitors; it is that He alone is, and that every competitor is either an inanimate object, a deceiving spirit, or a temporary human authority. History nods in agreement: pantheons pass, cults crumble, empires fall, but Israel remains—a people carried by promises that refuse to expire because the Promiser does not.

So here is the call and the comfort. Refuse the seduction of multiplicity; it always ends in fragmentation of the soul. Worship the One whose unity heals division. Do not dignify counterfeits with the title that belongs to the Maker of heaven and earth. Let the language be precise, because precision is a form of worship: Yahweh alone is God; there is no other (Isaiah 45:5). Let the evidence steady your steps: the nation He named still lives, the land He promised still speaks, the word He uttered still governs time. And let the analogies teach you to see. A lighthouse does not argue with the fog; it shines. A compass that is one degree off does not announce catastrophe; it quietly ensures it—unless corrected by a true north. A counterfeit can trick the fingers, but not the mint. In the end, the Scriptures do not invite you into a debate about a crowded sky; they invite you to stand beneath a single, unsetting sun. Worship there. Stand there. Build there. Yahweh is God, and there is no other.