Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

A message to the Believer…

There are no accidents in the Kingdom of Yahweh. There are appointments, alignments, and assignments, and there are detours men create when they seize holy things to serve earthly aims. If you follow the trail of the English Bible from its first appearance to the present, you do not find a straight line of covenant fidelity; you find a chain of custody stamped with seals of crowns, councils, committees, seminaries, denominational boards, and corporate publishers. You find printers’ marks and royal licenses, translation “rules” designed to protect ecclesiastical power, doctrinal notes inserted or forbidden by decree, and, in modern times, marketing departments, licensing contracts, and brand guardianship. You find a book multiplied to nearly the number of living souls on the planet, and that scale alone should make any sober mind ask who decided what those billions would read and why. If a compass is adjusted by one degree at its origin, the ship misses the harbor by miles; so too when the Word is bent at the source, an entire civilization lands on a different shore. This is not an accusation thrown in the dark; it is the pattern that emerges when we simply trace who translated, who backed them, why they did it, and what they got for doing it.

Begin where the English story begins. Wycliffe’s circle labored in the late 1300s to put Scripture into the tongue of the people. There was no crown hire, no episcopal stipend, no licensed desk inside a cathedral scriptorium. There were Lollards and lay patrons, there was risk, and there was the swift hand of prohibition when bishops realized that vernacular Scripture diluted clerical control. The ban on unauthorized English Bibles was not holy jealousy for purity; it was institutional preservation. This first episode is not a footnote—it sets the grammar of the next six centuries: when covenant hunger drives translation, institutions push back; when institutions command translation, the people are expected to sit still and receive. Then an incendiary genius named Tyndale, fueled by a merchant’s private patronage rather than royal favor, reached past Latin to the Greek and the Hebrew and put a sword into the hands of farmhands and shopkeepers. The price was prison and a pyre, but his phrases sank so deep into England’s speech that even his enemies could not easily uproot them. Already the pattern clarifies: when a man moves in fidelity rather than in office, the text gains fire and the translator loses safety.

Coverdale’s printed Bible followed, the first complete English Bible, supported by reforming patrons and continental presses, and it opened the gate for what came next—the crown itself deciding that if an English Bible must exist, it would be an English Bible it could control. The Great Bible under Henry VIII, engineered through Cromwell, was a state project with state aims: a uniform text in every parish, a single voice from every lectern, and printers whose livelihoods depended on the royal monopoly. The Bible was no longer merely a book; it was an instrument for building a national religious settlement in the king’s own image. Picture a mint that stamps currency—whoever controls the die controls the face; whoever controls the face controls the trade. From that point forward, translation and power walked hand in hand in the open.

When English exiles crossed the Channel during Marian persecution and published the Geneva Bible, they guided readers with vigorous marginal notes that took sides against tyranny, and the people loved it. The Geneva was not neutral parchment; it was a schoolmaster that taught readers how to read against the grain of absolutism. For that very reason, the bishops answered with the Bishops’ Bible, a pulpit standard designed to mute the Geneva’s edges. Institutions do not cede the ring; they commission their own fighters. On the Catholic side, the Counter-Reformation produced the Douay–Rheims, a confessional fortress built from the Vulgate with heavy annotation for catechesis, proving that Rome, too, understood translation as formation, not just communication. The point is not to pretend one side alone played this game; the point is to observe that every side did, because translation is power, and power always seeks its own.

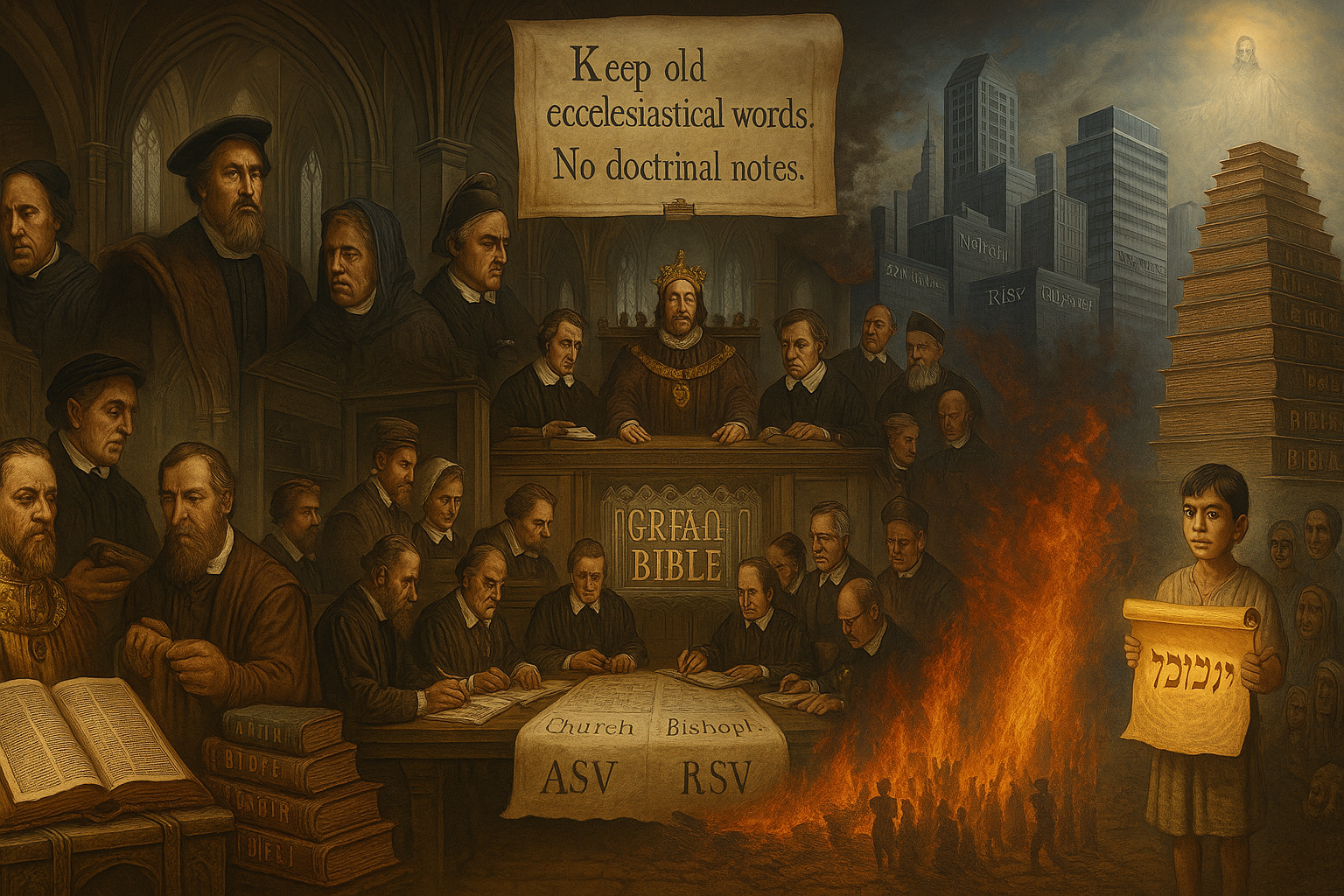

The hinge of the English tradition is the 1611 project commonly called the Authorized Version. Here the machinery is visible in daylight. After Hampton Court, the king set rules for the translators: keep the old ecclesiastical words so that structures remain unchallenged, forbid doctrinal marginal notes so that readers cannot be coached into resisting authority, and follow the already official text where possible to ensure continuity of tone. The translators were not put on a wage—but they lived in a system where the crown and bishops could reward with church livings, posts, and preferment. In modern terms, they were paid in kingship’s currency: access, station, security, and legacy. The result was a note-free national Bible whose very diction preserved the ascendancy of the church-as-institution and whose cadence became the sound of English piety for centuries. If you want to understand how a text can be holy in content and yet harnessed in form, study those rules. The sword remained a sword, but the hilt bore the sovereign’s seal.

From there the story passes through phases of consolidation and modernization. The Revised Version in the nineteenth century and the American Standard Version at the dawn of the twentieth were committee endeavors, birthed by convocations and publishers with names like Oxford, Cambridge, and Nelson. The stated aims were better manuscripts and updated language; the unstated outcomes were institutional prestige, reliable sales, and deepened press authority over the most printed text in the English world. By mid-century, the Revised Standard Version under the umbrella of the National Council of Churches became the lightning rod where textual criticism, mainline ecclesiology, and public controversy collided. It won seminaries and liturgies and set off bonfires in parking lots. Such firestorms prove what we are saying: translation has never been a neutral shuttle of words; it is the loom where a people’s theology and politics are woven.

Then the era of the modern Bible marketplace arrived. Translations gained owners and exclusive licenses; publishers gained portfolios; denominations gained house Bibles; and the language of “readability” and “accuracy” learned to coexist with the language of brand identity and market segmentation. The New American Standard Bible offered a formal-equivalence flag for readers trained to prize word-for-word discipline; the New International Version, owned by a mission agency and licensed to a commercial powerhouse, rode the balance of accuracy and readability into a decades-long market dominance that shaped sermons and small groups across continents; the New King James Version secured a classic cadence for a modern ear and became a pillar title anchoring a publisher’s catalog; the New Revised Standard Version secured liturgical prestige and university authority and then revised again for a new generation; the English Standard Version pressed the phrase “essentially literal” into a trademark, and revealed in one now-famous episode how a publisher’s policy can attempt to freeze a sacred text as a fixed brand statement before walking it back under public heat; the New Living Translation proved that dynamic equivalence, when executed by a large scholarly team, could capture an enormous popular audience; the Christian Standard Bible provided a denominational ecosystem its own translation to harmonize preaching, curricula, and product lines; the NET Bible changed the power equation by exposing the translators’ notes at scale, an admission that the real action is in the decision points; the New World Translation reminded everyone that when a sect owns the press and the committee, it also owns the doctrinal slant; and The Message demonstrated that one pastor’s ear can reshape the devotional habit of millions. In each case the stated aim sits beside the real outcomes: theological steering by committee design, institutional consolidation by licensing, market power by exclusive rights, and influence bought by readability on the one hand and brand trust on the other. If the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries married text to throne and miter, the twentieth and twenty-first married text to boardroom and brand.

Now lift your eyes from the timeline and look at the pattern. Who translated? Often committees recognizable by their churchmanship and institutional allegiances, or by their publisher’s business model, or both. Who backed them? Crowns, convocations, councils, foundations, denominational boards, and corporate publishers. Why did they do it? Publicly, for clarity and faithfulness; structurally, for unity, doctrinal boundary maintenance, liturgical stability, academic prestige, or market share. What did they get? In the early eras, preferment, pulpits, and the right to define orthodoxy; in the modern era, licensing revenue, imprints fortified by flagship titles, denominational lock-in, and reputational capital that keeps endowments filled and conference stages booked. When translation becomes a lever for social order, the lever is guarded. When it becomes a product, the product is managed. When it becomes a badge of identity, the badge is policed. Say it plainly: the English Bible has been the most successful instrument of religious formation ever printed in English, and because of that it has never been left unattended by those for whom formation is the practical means of power.

Someone will object that many translators were pious, that many patrons prayed, that many publishers sincerely desired good. All that may be granted without yielding the argument. Sincerity does not erase structure. A sincere pilot can still follow the wrong coordinates if the tower feeds him the numbers; a sincere committee can still be given rules that pre-decide outcomes; a sincere publisher can still assemble a portfolio whose economic survival requires maintaining certain reader expectations in certain markets. What matters is not whether individuals were nice but whether the system itself bent the Word toward its own survival. The evidence says it did, over and over again.

Follow one strand deeper, because it exposes the heart of the matter. Names in Scripture are not mere labels; they are covenant disclosures. When Yahweh entrusted the saving Name to Gabriel, it was spoken, not typeset. When Gabriel delivered it to Miriam, it was spoken, not copyedited. When the Messiah walked among His disciples, He called and was called by the Name, with breath and tongue and ear. That is how covenants are sealed—by voice and vow, not by printer’s ink. In human society, the simplest test of respect is whether you repeat the name someone gives you. If I tell you my name and you change it to accommodate your palate or your tribe’s comfort, you are not practicing hospitality; you are practicing ownership. The long habit of replacing the covenant Name Yehoshua with the substitute Jesus in Christianity is not a harmless preference; it is the signature move of a culture that learned to package heaven’s revelation for earthly convenience. The same pattern that protected “church” instead of “congregation,” that steered notes to guide or forbade notes to prevent, that selected base texts and translation philosophies to keep structures intact, also taught the world to be at ease with a substitute. You cannot be surprised that a civilization catechized by committees and brands would shrug at the switch of the Name, and you cannot be surprised that the poor—who rely on hearing, not on subscriptions and seminary—are the ones most easily cut off from the original sound of the covenant.

Think of the Word as living water and the translation apparatus as the aqueducts. If the aqueduct is bent, the water still arrives, but it arrives flavored by the stone and slowed by the turns chosen by engineers whose salaries depend on towns downstream. Think of the Word as open-source code and the centuries of councils, bishops, publishers, and committees as a closed, forked distribution with proprietary patches; the kernel remains recognizable, but the defaults, the APIs, and the shipped configuration steer the user to certain behaviors. Think of the Word as a letter from a Father, and the translation apparatus as postal inspectors with scissors, black markers, and rubber stamps; most of the message is delivered, but the high-voltage lines have been re-routed through switches owned by the state and the corporation. This is not cynicism; it is description.

So why insist, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the Word must be rewritten into English by someone under covenant relation with Yehoshua, for the least of us, and for the fulfillment of prophecy that the true gospel of the cure and covenant go to the four corners of the earth? Because the evidence compels it. Because the chain of custody shows continuous human handling that served power before it served the poor. Because revisions have multiplied not only clarity but confusion, creating a hall of mirrors where terms are softened here, sharpened there, and averaged elsewhere so that the median reader never senses the original edge. Because the Name at the center has been domesticated in the speech of Christianity, and the recovery of that Name in the mouths of ordinary people is itself a prophetic act that no committee can license. Because unless the text is reborn from covenant, it will continue to be curated by interests that cannot help but protect themselves. The least of us do not need one more brand; they need the Voice as it was breathed.

What would such a rewriting require, and why does it matter to say it aloud now? It would require a translator whose first allegiance is not to a throne, a board, a foundation, a catalog, or a conference schedule, but to Yahweh and to the body of people who will never sit in a seminary classroom. It would require the courage to retain covenant names and terms even when they grate against the habits of English ears trained by centuries of smoothing. It would require footpaths, not only footnotes: audio and testimony, homes and small rooms where the Name is spoken and heard and repeated until it becomes the natural language of prayer and obedience again. It would require an economy of distribution that is hostile to gatekeeping, a pedagogy that assumes the poor are not stupid but starved, and a posture that treats every choice of wording as a pastoral intervention rather than a market pitch. It would require the humility to be transparent about decision points, to expose translation judgments instead of hiding them behind the curtain of committee anonymity, yet without surrendering to the chaos of a thousand private paraphrases. It would require sacrifice, because breaking chains always does.

Someone will ask about proof, and they should. Proof lives in the record: in the royal rules that froze ecclesiastical terms, in the marginal wars of Geneva and the bishops, in the Counter-Reformation’s catechetical notes, in the Convocation minutes that launched committees, in the contracts that tied ownership to imprints, in the brand statements that tried to make a text permanent like a logo, in the exclusive licenses that turn Scripture into territory, in the denominational initiatives that harmonize wording with curriculum so that doctrine flows in a single channel. Proof lives in the sheer numbers that make any small decision in a translation ripple across billions of copies and centuries of sermons. Proof lives in the obvious reality that no single, independent, covenant-bonded translator has ever been allowed to deliver a mirror-fashion rendering from Hebrew and Greek into English at civilization scale without being either shut down by power or absorbed by it. The pattern speaks for itself, and it says that the time for a different pattern has come.

If you are listening as one of the least—if you have been told you are too unlearned to grasp the original, too busy to care, too poor to matter—hear this: heaven’s covenant was spoken for you first. If you are listening as one who has taught others, housed within the structures that have both preserved and pruned the Word, hear this: fidelity now requires repentance at the level of vocabulary and voice, not just at the level of intention. If you are listening as a skeptic who loves language but distrusts religion, hear this: the language here is not trying to recruit you into a brand; it is trying to recover a sound before it was domesticated.

The end of this road is not applause, a title, or a building with a donor wall. The end of this road is a people who can call on Yehoshua by the Name given, drink the Word clean, and carry it in their mouths to the ends of the earth. The end of this road is the least finally fed by a loaf that has not been sliced for palates and profits. The end of this road is prophecy moving from ink back into breath, from managed product back into living speech, until the four corners hear the cure and the covenant as they were spoken. When that happens, something more than a publishing milestone will have occurred. A circuit will have been closed, a vow kept, a promise fulfilled, and a trumpet prepared. Then the Father will not be asked to bless our editions; He will be heard in the voices of His people, and the Son will call as He was always going to call, and a world catechized by substitutes will learn to answer to the Name.

So this is the case and the call in one breath. The English Bible as we have inherited it is a palimpsest of power—royal, episcopal, academic, denominational, and commercial. It has preserved much and obscured much, brought light and cast large shadows, and it bears the fingerprints of men on every page margin even as it bears the heartbeat of Yahweh in every true line. That mixture is no longer tolerable in an hour when the world has nearly one copy per person and yet is starving for the sound that gives life. The Word must be rewritten by one under covenant relation with Yehoshua, for the least, and in service of the prophecy that the true gospel of the cure and of the covenant will reach the four winds. Not to invent a novelty, but to remove the hands that have been steering it, to restore the Name that has been softened, and to loose the voice that has been restrained. The river wants to run. Remove the gates. Let it run.