Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

A message to the New Creation…

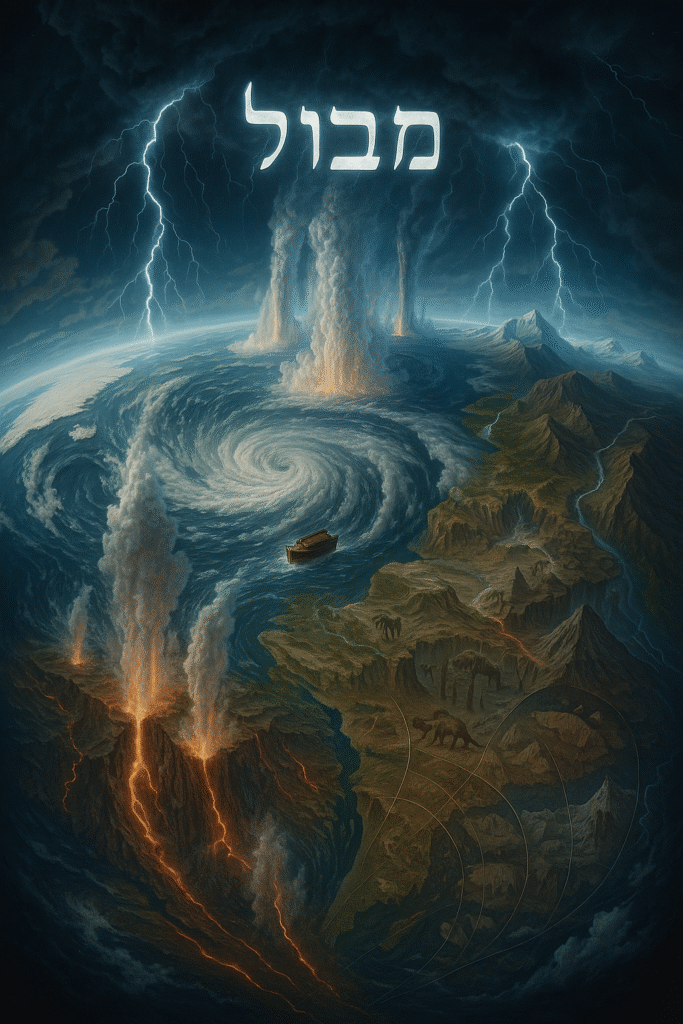

There are two breakers in the faith-circuit that keep many from ever carrying the current of real belief. The first is creation: was the universe truly formed in six days? We closed that breaker by restoring yom to its native meaning as a stage of divine construction rather than a mechanical clock. The second breaker is the Flood. If the creation account establishes the blueprint, the Flood explains the global reset that shaped the present world. If either remains unbelievable, the circuit stays open and the current never runs. What follows is not an appeal to sentiment or tradition; it is the text, in its own languages, speaking for itself with a clarity that modern shortcuts have obscured. We will hear God’s decree, watch the mechanics He describes, test the exclusivity of His chosen terms, and then stand under Yehoshua’s own witness that seals the matter. When the Hebrew and Greek are allowed to speak, the Flood is revealed as a singular, global, divinely governed cataclysm that remade the inhabited world.

The place to begin is where God Himself announces the event. In Genesis 6:11–13 the diagnosis is comprehensive: the earth is corrupt before God and filled with chamas, predatory violence; all flesh has ruined its God-given way. God sets a terminal horizon: the end of all flesh has come before Him, and He will destroy them with the earth. This frames the judgment as proportionate to a universal corruption; the ruin that humanity inflicted upon creation will be judicially mirrored in a universal unmaking. In Genesis 6:17 God speaks with solemn emphasis: Behold, I—yes, I—am bringing the mabbul of waters upon the earth to destroy all flesh in which is the breath of life from under heaven; everything that is on the earth shall perish. The word mabbul is not a generic downpour; it is the formal name of the Flood and carries, in its very letters, the shape of the act. Mem, bet, vav, lamed: waters that enclose the whole house of the world, joined and governed under divine authority. It is an enclosing, domain-wide inundation, not a regional surge. The phrase “all flesh” functions as a totalizer, the phrase “from under the heavens” marks the vertical boundary of everything within the breathable realm, and the verb “shall perish” targets the expiration of the breath-line in every organism outside the ark. The language is architected to remove loopholes. Genesis 7:1–4 moves from decree to countdown. God summons Noah into preservation, sets seven days, initiates a causative rain for forty days and forty nights, and declares that He will wipe out every standing life He constituted from the face of the ground. Wipe out means erase to nothing; every standing life means the full set of breathing creatures that populate the face of the earth. The scope, motive, timing, and target are all His statements, not ours.

When the day arrives, Genesis 7:11–12 opens the machinery. The text names a dual-front cataclysm that forbids small thinking. All the fountains of the great deep burst open, and the floodgates of the heavens were opened. The verb for “burst” is a violent rupture; the term “fountains of the deep” names the subterranean and suboceanic reservoirs tied back to the primeval tehom in Genesis 1:2. At the same moment, the sluice-gates in the heavenly vault swing open, releasing the waters above. The rain that falls is the atmospheric expression of those opened gates and continues in saturating force for forty days and forty nights. The earth drowns from below and above together; the crust is rent, reservoirs erupt, the firmament releases, and the breathable realm is overwhelmed. The narrative’s verbs point to decisive acts, not slow processes; its nouns point to the whole inhabited domain, not a drainage basin. The mechanics serve the decree, and the decree serves the judgment’s scope.

The exclusivity of the vocabulary locks the interpretation. In the Tanakh, mabbul appears only of Noah’s Flood and never of anything else. It names a once-for-all event whose aftermath becomes a chronological anchor, an epochal memory, and a covenant boundary that God swears never to cross again by water. That oath matters: “never again shall there be a mabbul to destroy the earth” is nonsense if mabbul meant “a very large local flood,” because local floods have recurred endlessly. The promise has force only if the event was global and unique. Even the Psalmist remembers the Lord enthroned at the mabbul, sovereign in the hour He unmade the world that had unmade itself. The term’s exclusivity is the textual guardrail against our shrinking of the story.

Then comes the witness that no disciple of the Messiah can evade. Yehoshua speaks of the Flood in Matthew 24:37–39 and Luke 17:26–27 and fixes it as the template for His own royal appearing. He does not treat it as a myth or a local lesson; He names it as the kataklysmos and builds His warning upon its nature. People ate, drank, married, and were given in marriage until the day Noah entered the ark, and they did not understand until the kataklysmos came and took them all away. The grammar is decisive. The comparative formula “just as… so also” binds the Flood to His coming, so that the features of the first define the features of the second. The ignorance persists until a sudden point; the cataclysm arrives as a single decisive event; the verb removes all without exception. His analogy collapses if the Flood was partial, regional, or gradual, for His coming will be universal, global, and inescapably total to all outside His provision. Peter follows the same line and says God brought a kataklysmos upon the world of the ungodly while preserving Noah, calling the event what it was: a world-judgment with a world-remnant.

When we fuse these layers—God’s decree and countdown, the dual-source mechanics, the exclusivity of mabbul, and Yehoshua’s kataklysmos—the case is closed. The Flood is not a devotional tale; it is the measured, governed, planet-scale unmaking that God Himself announced, executed, remembered, and bound by covenant never to repeat. The ark was not a metaphor; it was the preservation technology that carried forward the kinds God purposed to repopulate the earth. The waters did not linger as a regional inconvenience; they enclosed the whole house under the heavens and cut off the breath-line of every creature not sealed within God’s provision. To disbelieve this is not to disagree with an interpretation; it is to disbelieve God’s own testimony and the Messiah’s own warning. And that disbelief is precisely what keeps the breaker open and the current dead.

But there is a gift hidden in this severity. The creation account taught us that the Word of God structures reality in stages until it is complete. The Flood account teaches us that the same Word can decommission a ruined world and carry forward a remnant into a renewed order. Creation and Flood are not embarrassments to be explained away; they are the very scaffolding of biblical history and prophecy. Once you let the languages speak, once you accept God’s decree on His terms, the circuit clicks shut. Faith ceases to be an aspirational feeling and becomes a live current grounded in agreement with what He has said. You do not merely believe in God; you believe God. And from that moment, the text no longer strains against modern reductions. It breathes. It governs. It warns. It preserves. It prepares you for the next great “just as… so also,” when the One who sat enthroned at the mabbul will come as King to judge and to renew again.

And the earth itself bears witness that such a cataclysm has taken place. The highest rocks on Earth tell a marine story. The summit pyramid of Everest is banded limestone packed with fossils of shallow-sea organisms, a remnant of the ancient seafloor now hoisted nearly nine kilometers into the sky by crustal collision. Geological surveys point out that the “Yellow Band” and related summit strata are marine in origin, preserving trilobites, crinoids, brachiopods, and other Ordovician sea life; the only way marine limestones arrive at the top of the world is if vast sediments were laid down under water and later driven upward on a continent-scale tectonic stage. That Everest and other Himalayan peaks carry this signature is not an oddity; it is a global pattern—ocean deposits now seated in the world’s loftiest ranges—showing a planet once extensively under water and then violently rearranged. The mechanics that lifted those beds are plate collisions, but the raw fact they had to be deposited first, as marine sediments, is inescapable and entirely in line with a world-engulfing inundation followed by wholesale reconfiguration.

Where sediments came fast and deep, entire forests were entombed standing up. Along the Bay of Fundy at the Joggins Fossil Cliffs—an international reference site—multiple levels of upright fossil trees pierce successive rock units, a phenomenon that can only happen when burial outruns decay. These “polystrate” trees, preserved through stacked beds, are not a curiosity but a diagnostic of rapid, high-energy deposition; and here they occur in series, not as isolated specimens. The official descriptions emphasize the repeated horizons of upright trunks and the completeness of the fossil forests they record—exactly what one expects from pulses of fast, water-laid sediment packaging whole ecosystems in minutes to hours, not millennia.

In bed after bed across continents, the sediments themselves bear the scars of being dumped, slumped, and deformed while still soft. Geologists catalog “soft-sediment deformation structures”—load casts, convolute bedding, slump folds, fluid-escape pipes, seismites—features that form when thick packages of unlithified sand and mud are rapidly piled, shaken, and liquefied, then frozen into stone before they can relax. These are not the textures of leisurely accumulation; they are the fingerprints of speed, thickness, and energy, the sedimentary equivalent of skid marks and buckled asphalt after a pileup. When such structures appear widely and at multiple horizons, they testify to repeated catastrophic pulses—just what a long, staged Flood and its recession would imprint into the crust.

If someone doubts what water can do quickly, the Channeled Scablands of the U.S. Pacific Northwest supply the demonstration. For decades the idea that eastern Washington’s immense coulees, cataracts, and giant current ripples were carved by sudden megafloods was resisted; now it is geological canon. At the close of the Ice Age, ice-dammed Lake Missoula repeatedly failed, releasing walls of water that reorganized entire landscapes in hours to days. The point is not that the Scablands were the Flood; it is that the physics of catastrophic water flow is real and observed, and that continent-scale surfaces can be cut, stripped, and replumbed by pulses measured in days, not epochs. This is precisely the kind of energy a planet-wide deluge and its drawdown would unleash.

Even in the Grand Canyon system—held up as a monument to slow erosion—there is hard evidence of catastrophic phases. Peer-reviewed work quantifies enormous outburst floods on the Colorado River when lava dams failed inside the canyon, unleashing peak discharges far beyond modern norms and leaving geomorphic signatures of short-lived but titanic flows. The canyon country remembers cataclysms, and those cataclysms track with the very kind of hydraulic power a global deluge’s surge and retreat can deliver.

The fossil record itself often reads like a disaster narrative written in bone. Alberta’s Hilda mega-bonebed extends for kilometers and holds the jumbled remains of a single horned dinosaur genus in astonishing numbers, a mass-mortality deposit now documented in the technical literature. Far from tidy, articulated skeletons gently buried in place, these assemblages show herds overwhelmed, transported, and buried en masse under sediment pulses, with carcasses mixed, disarticulated, and concentrated in laterally extensive sheets. Mega-bonebeds of this sort are not the language of slow attrition; they are the stack trace of violent, watery death and rapid entombment, consistent with widespread flooding on large, low-relief plains.

At the far edge of preservation, even the microstructure of dinosaur bones has returned surprises that imply swifter burial and sealing than textbooks long allowed. Reports have described soft-tissue vessels, collagen fragments, and cell-like microstructures persisting within demineralized bones—features that demand exceptional geochemical conditions and rapid isolation from degraders. Whatever time scale one adopts, the mechanism is plain: bones had to be sealed from oxygenated waters, microbes, and scavengers quickly enough to preserve delicate architectures, an outcome easier to achieve in thick, swiftly piled sediments than in thin, intermittent drapes.

Beneath the dramatic outcrops, the continents themselves wear blankets of sediment that span regions the size of countries—packages bounded by unconformities and traceable for thousands of kilometers. Stratigraphers call these cratonic or Sloss sequences: continent-scale transgressive–regressive stacks laid down when seas overran the interiors and then withdrew, leaving layer-cake records of broad, shallow inundation. The existence of such megasequences demonstrates that interior continents can be drowned and resurfaced on a vast scale; it is a structural fact of the geologic record that fits hand-in-glove with the idea of a world under water and then a world in retreat.

At the same time, the broader architecture of the continents supports a single-landmass past and subsequent violent partitioning. The evidence for Pangea is not a jigsaw map on a classroom wall; it is the stitching of mountain belts and rock suites across oceans—the Appalachians in North America tied into the Caledonides and Atlas ranges across the Atlantic, matching terranes, glacial deposits, and fossil provinces once contiguous and now sundered. The supercontinent thesis is now bedrock, and the collision seams and suture zones that built our ranges are the torn hems of a world that was joined and then ripped. A global inundation followed by tectonic upheaval and dispersal fits the gross narrative the rocks themselves recite.

Even the rivers testify. Drainage systems that today appear to defy topography—rivers that slice straight through mountain ridges to form narrow water gaps—are reminders that channels can predate uplift and that enormous, short-lived flows can capture and entrench courses through rising rock. Water has a memory, and when the earth heaves under it while discharge is still great, it cuts where it is already going, sawing corridors through stone as if the mountains were afterthoughts. Such features are exactly the kind of landscape residue a retreating, world-scale flood and post-flood uplift would leave across orogens.

And at the frozen margins of the planet, the ice caps preserve their own testimony. Greenland and Antarctica hold thick sequences of ice, but embedded in these frozen archives are bands of debris, ash, and chemical anomalies that point to sudden, massive changes in deposition. Ice cores reveal abrupt shifts in trapped gas composition, dust concentration, and isotopic signatures—jumps that in some cases appear over the span of a single year’s layer rather than gradually over centuries. Such chemical and particulate “event markers” match the expectations of a world destabilized by the bursting of the fountains of the great deep and the opening of the windows of heaven. Massive influxes of vapor into the upper atmosphere, followed by rapid condensation in a cooling post-flood world, would have built the early ice sheets with intense snowfall rates, locking away a record of climatic chaos rather than gentle oscillation. Even the presence of ocean-derived salts deep within Antarctic cores testifies to global-scale sea spray transport, something consistent with extreme storms over warm post-flood seas. In this reading, the ice caps are not the slow diary of a placid planet, but the shock-frozen annex to the Flood’s archive, holding in crystalline detail the aftermath of the only mabbul the earth has ever seen.

Taken together, these lines of evidence—marine rocks and fossils lofted to the roof of the world, forests entombed upright through stacked beds, sediments deformed while still soft, regions carved wholesale by megafloods, canyons that remember violent pulses, bonebeds that speak of mass death and rapid burial, continent-scale sedimentary packages, sutured mountain belts from a once-joined world, rivers that hold their course through rising stone, and ice caps that lock away the chemistry of catastrophe—do not whisper a story opposed to Scripture. They tell the same one, in the slower, stubborn tongue of stone and ice. The Bible gives us the decree, the mechanics, and the scope; the planet bears the scars of exactly such a thing. Faith does not need these confirmations to be true, but the world often does, and when Scripture and strata line up as they do here, the circuit that was open for so many can finally close and carry current.