Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

This deep dive is solely in the context of my work , and a powerful message to those who simply don’t know what they’re talking about .

Imagine someone scoffing at the footnote on your work and saying, “You used AI — it isn’t credible.” They expect that to land like an accusation, as if a tool somehow carves away authority from an author. Let’s be blunt: that reaction tells you everything you need to know about the person saying it. It’s the reflex of someone scared, undereducated in method, or more interested in moral posturing than intellectual honesty. They clutch the word “AI” like a cudgel because they don’t know how to examine process, responsibility, or authorship. They want a shortcut — a one-word dismissal that substitutes for argument. That’s not critique. That’s a tantrum disguised as morality.

At bottom, artificial intelligence, the term people use in conversation, is advanced software. It is a pattern-recognition engine that, when trained on enormous amounts of data, predicts what comes next: words, images, structures, calculations. It is a machine that echoes statistical likelihoods. Put simply, it’s a prediction tool. Nothing mystical lives inside it. It does not receive revelation, it does not own conscience, and it does not possess a covenant with God. It is math, models, and example-driven probabilities wrapped in code. If you want theology, ethics, or authority, that comes from a person who stands accountable for what is said.

A hammer is not a house. The carpenter is. The hammer accelerates the process, makes certain tasks possible, and amplifies power. But the design, the decision to build, the choice of materials, the placement of each nail — those are human responsibilities. So it is with AI. It helps draft, edit, and assemble. It does not supply the formative vision, the covenantal discernment, or the moral accountability. Calling the hammer “cheating” because it did its job is absurd.

When someone shouts that AI is cheating, they are revealing one or more of five things, fear of change, ignorance of how tools work, anxiety about truth, romantic nostalgia for “pure labor,” or a legitimate concern about misuse dressed as moral certainty. Fear of displacement makes people defensive. Lack of understanding leads to sweeping condemnations. Anxiety about accuracy is a reasonable prompt for standards, not a reason to condemn every tool. Romantic nostalgia often imagines that manual toil equals moral worth — which is inconsistent and selective when scaled across history. And when misuse happens — plagiarism, fake scholarship, or deliberate deception — we must call that out. But the answer to misuse is governance, verification, and ethics, not blanket hatred of the instrument.

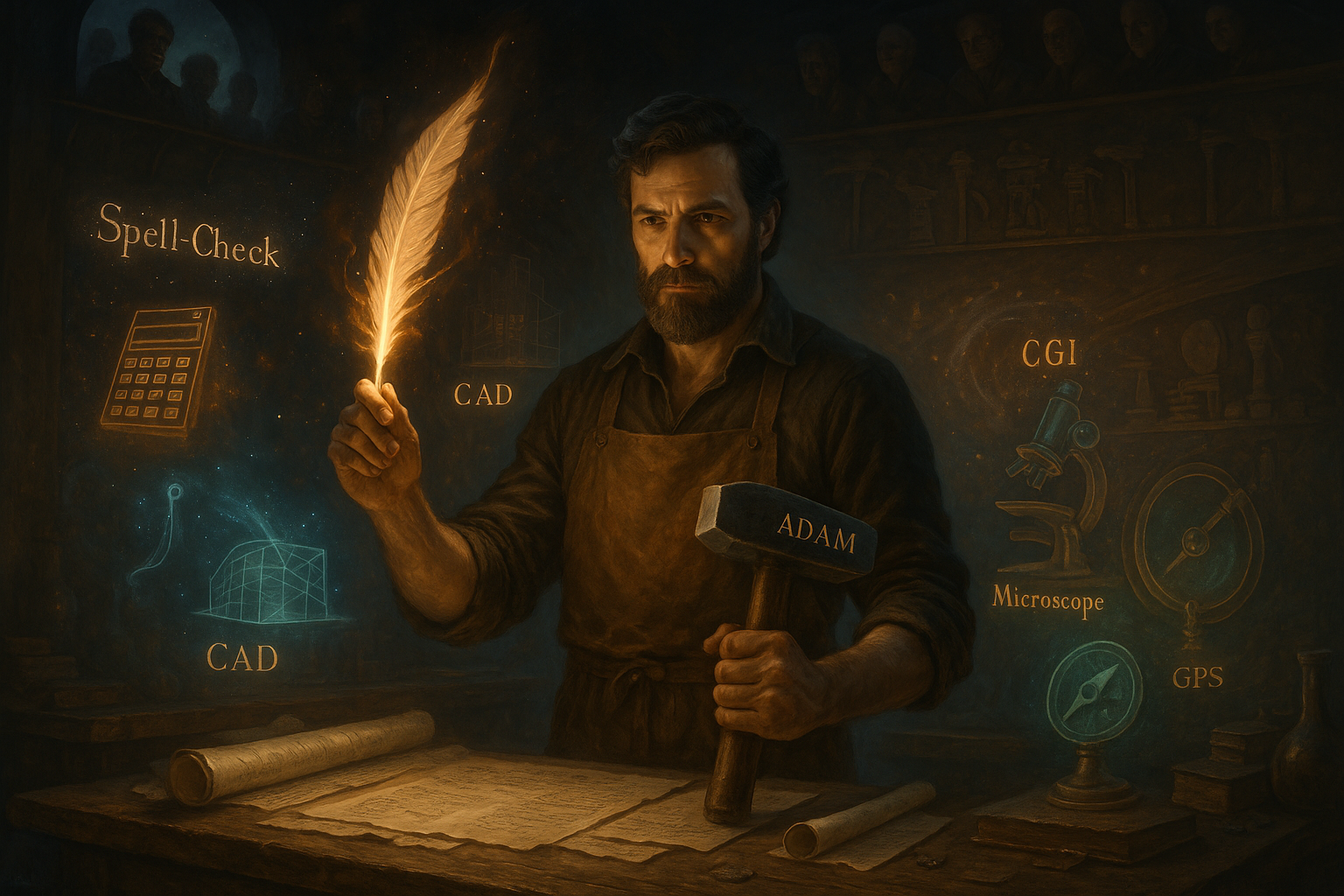

Tools have always threatened and then freed us Look back at earlier “cheating” panics and you find the same pattern. Spell-check was once smirked at: “real writers don’t need help.” Calculators were slurred as an easy way out. Computer-aided design was once a blasphemy against “true craft.” CGI was dismissed as fake. Yet architects erect taller, safer buildings; filmmakers tell richer stories; scientists see far deeper into the body; writers produce cleaner, clearer prose. These tools extended human reach. They did not replace the person who carries responsibility for truth. If you accept microscopes in medicine and cameras in journalism, you have no principled ground from which to declare AI cheating. The objection collapses into sentimentalism or ignorance.

Cheating is a moral act, not a technological condition. Cheating is deception, claiming credit you do not deserve, knowingly passing off another’s labor as your own, or using a tool to perpetrate a lie. If a student uses a calculator when calculators are banned, that student cheats. If a novelist uses copy-paste from another author and claims it as original, that author cheats. Tools themselves are morally neutral. The moral failure lies in how they are used and represented.

Nothing protects credibility like clarity about process. If you used a tool, say so. Explain what you did, how you checked it, and where the spiritual and intellectual authority sits. An honest, simple disclosure looks like this: “Drafting and formatting assistance was provided by an AI tool named. All theological claims, original-language analysis, and final verifications were authored and confirmed by the writer.” Disclosure is not a confession of weakness; it’s an assertion of accountability. It reads: here is what the tool did, here is what the human did, and here is my willingness to stand responsible for every claim.

This should be plain, but it often isn’t. AI cannot commune with God. It cannot hold covenant. It cannot carry prophetic accountability. It cannot bear the weight of life experience, moral consequence, or spiritual discernment. It cannot repent, intercede, or stand in the pulpit and answer for a teaching. Those things belong to the person, not to a model trained on other people’s patterns. You, the writer, the teacher, the leader — you own the conclusions. The tool only helps articulate them.

If AI is to be used at all, it must be handled ethically and with wisdom, never as a shortcut to avoid responsibility. Its proper place is in the early stages, where it can help with drafting and structure, but it must never be treated as the final authority in matters of theology or truth. The tool can shape form and flow, but the human must always supply substance. Every suggestion it produces should be taken only as a lead, then verified against trustworthy sources such as HALOT, BDAG, and the primary texts themselves. Nothing is accepted until it has been checked and confirmed. The voice of the writer must also remain intact, which means editing until the cadence, vocabulary, and tone are unmistakably one’s own. The record of the work should be preserved in a trail of drafts, showing how ideas were refined from first sketch to finished form, so that authorship and progression are beyond dispute. Transparency must always accompany the process, not as a defensive apology but as a confident statement of integrity. And perhaps most importantly, discernment must never be outsourced. Productivity may be accelerated by a tool, but the soul of the work remains safeguarded only through prayer, study, and accountability. The tool may assist, but the burden of responsibility will always rest on the one who writes, teaches, and stands behind the words.

When the inevitable cheap shot comes — the sneer that your work is somehow invalid because AI touched it — the best response is short, sharp, and anchored in authority. One might simply say, “Yes, I used AI to assist with drafting and structure. The theology, original-language work, and final verification are mine.” Or, in a more academic setting, it may sound like, “My method includes AI-assisted drafting. All exegetical claims were checked against HALOT, BDAG, and primary manuscripts, and final responsibility rests with me.” And for the quick hit on social media, the line could be, “Tools don’t cheat. People do when they lie about sources. I verified and signed off on everything.” Each version is direct, avoids moralizing, and makes it clear that the authority belongs to the author, not the tool. The key is not to defend nervously but to respond with calm ownership that leaves no room for doubt about who carries the responsibility.

And when critics persist in pretending that AI is some alien magic that cancels human skill, the most effective strategy is to collapse their illusion with analogies so obvious they sting. Calling AI cheating is like calling a hammer cheating because a house required it. Spell-check didn’t make authors out of empty minds. Calculators didn’t erase intelligence; they multiplied it. CAD didn’t falsify architecture; it made taller, safer structures possible. CGI didn’t kill storytelling; it gave new worlds visibility. Microscopes didn’t invent germs; they simply revealed what was already there. GPS didn’t nullify navigation; it made travel precise instead of uncertain. These are not clever word games; they are the plain facts of history. Every age has seen new tools provoke shallow outrage before those same tools became essential. AI is no different, and those who rail against it reveal less about the tool and more about their own unwillingness to think past their fear

There’s a posture required, humility in method and courage in accountability. Humility says: I used a tool and I will show my work. Courage says: I will stand on my claims and welcome scrutiny. When you combine those two, you put panic back into the hands of the critic and you return the conversation to proof, not posturing.

When questions arise about credibility, the simplest way to disarm them is with transparency. Place a clear line under your title or byline so that no one is left guessing about what was done and by whom. It can read: “Draft and formatting assistance were provided by an AI tool. All theological, original-language, and exegetical conclusions are the work and responsibility of the author. Sources and draft history are available on request.” That single sentence is more than a disclosure; it is a declaration of ownership and accountability. It separates the tool from the author and shows that the responsibility for truth, accuracy, and authority rests on human shoulders.

But a line alone is not enough; there is also a discipline to be practiced whenever a tool has been involved. Every claim must be verified against primary sources rather than assumed. Every original-language analysis should be run through trusted lexicons such as HALOT or BDAG to ensure that the foundation is sound. The draft should be shaped and edited until the cadence, tone, and authority are unmistakably that of the author, not the tool. There should be a record of progression, with dated drafts that demonstrate authorship and development, so no one can accuse the process of being fabricated after the fact. Disclosure should never be treated as optional but as part of the integrity of the work. And above all, the final act must be spiritual: praying through the words, testing them against conviction, and submitting them to accountability so that they are not only correct but faithful.

This is how credibility is protected and projection remains strong. Not by hiding the tool, not by pretending it wasn’t used, but by showing that it has its place as an instrument while the responsibility for truth never leaves the hands of the one who speaks.

When someone throws “AI” like an insult, answer by exposing the insult’s poverty. Ask: which part of the work do you distrust — the logic, the facts, the quotations? If they can’t point to a single error, ask them to produce evidence their charge means anything. Often they will retreat into ad hominem noise. That retreat should clarify the debate for any sensible onlooker: their position has no content; it is fear dressed as principle.

There is a deeper truth here that must be said plainly and unambiguously. Tools cannot bear covenant responsibility. If a teaching moves people, blesses them, or harms them, the accountability does not pass to the algorithm. It stays with the person who taught. That is why transparency matters: you cannot hide behind a “machine” when you stand before people or the Judge. The use of tools does not lessen your duty to speak truth, live ethically, and pursue righteousness in scholarship.

To those who fling the word “AI” as if it were a verdict. Your cheap shot betrays your laziness. It reveals a refusal to engage with method, an incapacity or unwillingness to examine evidence, and a hunger for moral posturing rather than honest critique. To the careful worker, the scholar, the pastor, the writer who uses tools responsibly: hold your method open, show your drafts, cite your sources, and keep your name on your work. Tools have always amplified human reach. They have also always exposed those who can’t answer for their work.