Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

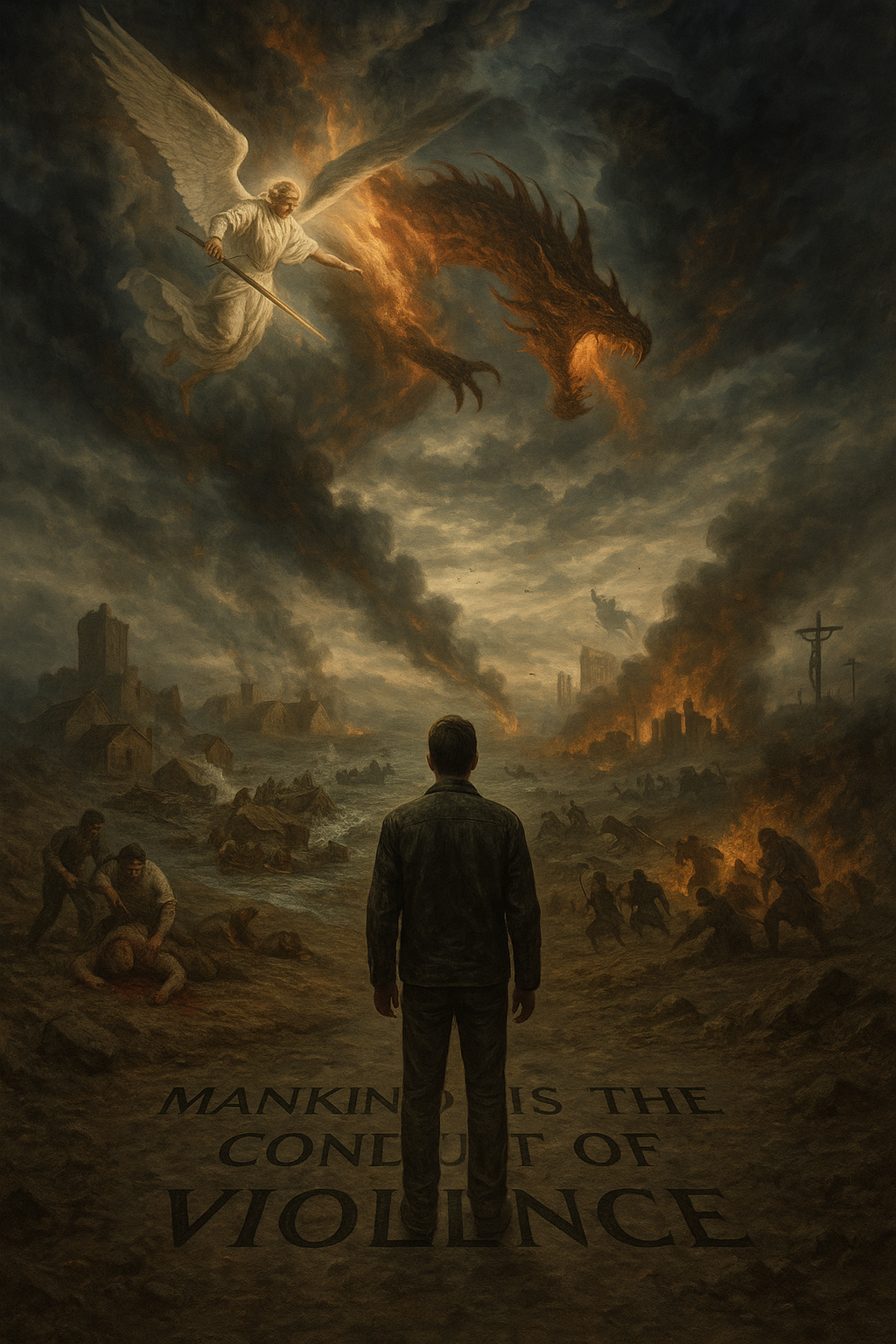

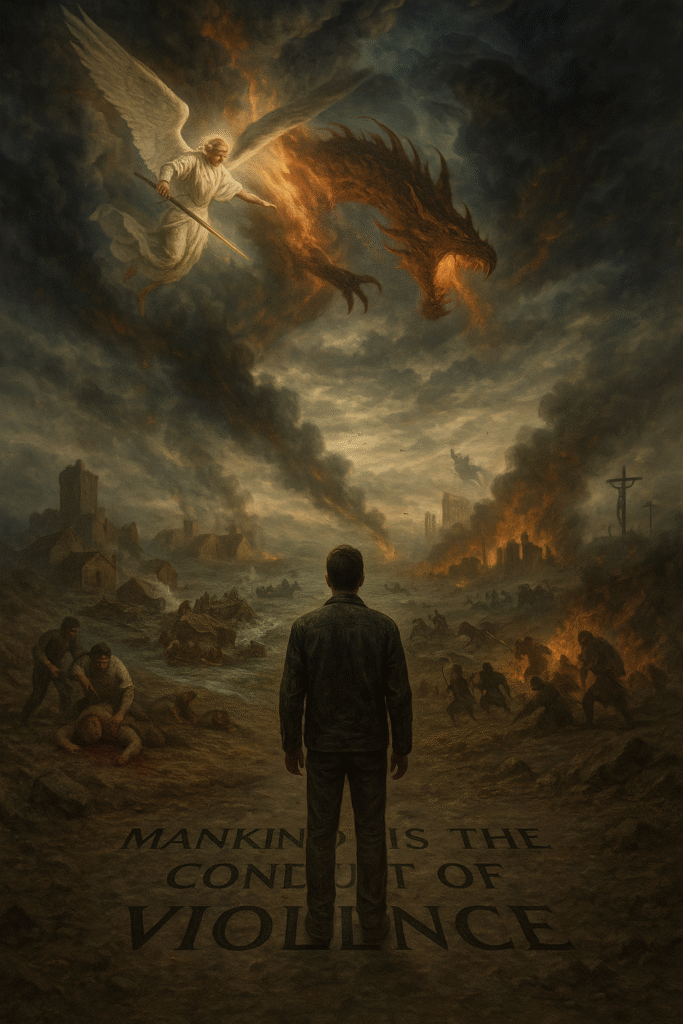

“Violence is never the answer….” You’re right, it’s the engine.

People repeat the slogan “violence is never the answer” like it’s a universal law, but the world we actually live in testifies against that claim at every turn. The United States was not daydreamed into existence; it was ripped into being through the Revolutionary War, held together by a Civil War soaked in blood, and expanded across a continent in the shadow of crushed nations and the genocide of Native peoples. These are not fringe footnotes. They are the scaffolding of the national story. Even the supposed counterexample—mid-twentieth-century nonviolence—doesn’t erase violence; it exposes it. The Civil Rights movement forced the nation to look at its own brutality in the mirror, and yet here we are, generations later, with racism, bigotry, homophobia, misogyny, and malice not vanquished but adapted—hidden in structures, policies, and polite phrases, often voiced from the very institutions that claim moral authority. To insist “violence is never the answer” in the face of this record is not moral clarity; it’s selective amnesia dressed up as virtue.

At the core of this is something people don’t want to admit: the human creature is violent by nature. That isn’t a moral endorsement; it’s an observation so consistent across time that denying it feels like denying gravity. We eat, compete, defend, conquer, and retaliate; we elevate tribes and mark enemies; we tell stories that sanctify our own battles and demonize others’. Say it plainly: mankind is the conduit of violence. Telling a human community “violence is never the answer” is like telling a fish “water is never the medium.” It doesn’t even understand the sentence. And if you want an image that refuses to blink—imagine standing in front of a starving lion and announcing, “I don’t believe in violence.” The lion will offer you no philosophical debate. Denial is not a shield. Reality is not negotiated by slogans; it asserts itself. That is not cynicism; that is sobriety.

Here’s the crucial distinction: this is not a prescriptive sermon inviting bloodshed; it is a descriptive reckoning with the world as it is and has been. We are not here to sell a solution that has never actually governed history. We are here to expose the pattern. Violence is not only a destroyer; it is a shaper. Think of the surgeon’s scalpel: the same sharpness that can murder can also cut a tumor free. Think of wildfire: it devours, yet it also clears underbrush so a forest can renew. Think of tectonic plates: earthquakes topple cities, yet those same pressures raise mountain ranges and set rivers in their courses. Violence is a force; what varies is who wields it, why, and what world is born in its wake. To pretend the force does not exist because we wish it didn’t is to live unprepared, unguarded, and untruthful.

Bring faith into the conversation and the pattern does not soften—it sharpens. Scripture does not sanitize human history. It records it. The Bible does not present a peace-pamphlet with a few regrettable outliers. It presents a cosmos at war, a humanity awash in blood and tears, and a God who judges and delivers through events that reorder the world with terrible force. The point here isn’t to adjudicate every case as “righteous” or “unrighteous”—the point is that violence is present from the first act of rebellion to the last act of judgment, and the people in the middle are not spectators; they are participants and instruments.

If we are honest about sequence, violence does not begin on Earth. It begins in heaven. John’s vision in Revelation depicts a war above: Michael and his angels against the dragon and his angels. The dragon is cast down. That is expulsion by force. That is an eviction conducted by power, not a negotiation secured by consensus. Before Cain ever lifted a hand, the cosmos had already witnessed conflict, defeat, and banishment. The Earth, in that telling, isn’t the birthplace of violence; it’s the battlefield where a defeated rebel takes his rage, and humanity becomes the conduit through which his malice and our own mingle and multiply.

Step into Genesis and the pattern thickens. Within a single generation, Cain rises against Abel and the ground drinks blood. The text describes a world filled with violence before the flood; the deluge is judgment by water that wipes a generation’s breath from the air and leaves a remnant. Babel is not a slaughter but it is coercive dispersion—language severed, peoples scattered, the tower dream broken by force from beyond. Sodom and Gomorrah do not collapse under the weight of a stern lecture; fire falls, cities are erased, and the valley remembers. Violence is not a late contamination of an otherwise tranquil garden civilization; it is the weather system of fallen existence.

The patriarchal narratives do not break the weather; they live inside it. Abraham arms his men to rescue Lot and cuts down kings to liberate captives. Covenant promises arrive in a world where altars are built under open skies that have seen slaughter. Jacob and Esau are twins whose rivalry threatens blood; reconciliation comes only after a night of wrestling and a lifetime of repercussions. Joseph is thrown into a pit by his brothers and trafficked into slavery; his rise in Egypt saves many lives but the road there is paved with human cruelty. Family, in Scripture, is not a safe room sealed off from violence; it is often the stage where violence is conceived, resisted, and redeemed.

Exodus, the story of deliverance par excellence, is framed by violence from first to last. Pharaoh’s state power crushes Israel with oppression; the plagues strike Egypt with escalating blows; the firstborn die; the sea closes over an army and turns triumphal chariots into sinking coffins. Sinai’s thunder reveals a holy presence that melts rock and terrifies flesh; the golden calf episode brings the sword into the camp; and the generation that would not believe dies in the wilderness. The entry into Canaan is not an interfaith colloquy; it is contested ground, cities besieged, walls fallen, and peoples displaced by judgment. The moral discomfort of these narratives is real—and that is exactly the point. Scripture refuses to let us pretend the world is a frictionless field where good ideas win without cost. It shows us a world where power is answered by power, and holiness collides with corruption at high speed.

The era of Judges and the monarchy is an unspooling of cycles where violence is both the instrument and the consequence of apostasy. Samson’s riddle gives way to jawbone warfare. Tribal civil war nearly erases a tribe from Israel. Saul hunts David; David fights Philistines; Israel fights Israel; and the palace itself becomes a crime scene where Uriah’s blood slicks the floor of national memory. The prophets will later name the triad of judgment—sword, famine, pestilence—like tolling bells, and those bells will ring from Damascus to Jerusalem to Babylon. Assyria razes; Babylon burns; exile drags chains across the thresholds of kings and carpenters alike. The prophets weep over this, but they do not deny it. They announce it, frame it, interpret it: if a nation sows violence, it will reap storm.

Turn to the prophets themselves and you hear the vocabulary of force without euphemism. They speak of sieges and spears, fields salted and cities razed, mothers bereft and kings humbled, not because they are bloodthirsty but because they refuse to trade in fantasies. Yahweh is not presented as a municipal chaplain muttering blessings over ceremonies; He is the Lord of hosts, the commander who raises and restrains nations, who brings down pride with a word and lifts up the lowly with a hand that can shake the earth. The prophetic imagination is not a pacified meadow; it is a thunderhead that sees judgment rolling in and calls it by name.

The Gospels do not exit this landscape; they intensify it at the precise point where many expect them to dissolve it. Yehoshua is born into an empire that slaughters infants to protect a paranoid king. He preaches the reign of God and tells His followers to turn the other cheek—a command that exposes and shames the cycle of personal retaliation—but the central symbol of His mission is not a wreath or a diploma; it is a cross. The crucifixion is state-sanctioned torture and execution, a public spectacle of Roman power. The lash, the nails, the spear—this is violence concentrated into a single body. The paradox is not that violence disappears in the Gospel but that it is gathered and transfigured. The most famous act in Christian memory is not a peaceful graduation from conflict but a violent death that becomes the axis of salvation. Even Yehoshua’s parables do not pretend away force: tenants murder the heir, a king sends an army to burn a city in a story, and judgment imagery remains electric. Turning the other cheek does not abolish the world’s appetite for harm; it judges it, exposes it, and routes the disciple’s personal response through a different kingdom.

Acts and the early Church step into the same wind. Stephen is stoned while his face shines; Saul ravages assemblies before becoming their most hunted herald; apostles are beaten, imprisoned, threatened, and scattered; martyrs seal their testimony with blood, and the empire that prided itself on order crucifies, beheads, and burns those who will not call Caesar lord. The letters are written by a man who bears on his back the marks of lashes, the fatigue of shipwreck, and the ache of shackles. This is the soil from which the Church grows—not because suffering is a fetish, but because the world into which the message goes is not neutral. It resists. It strikes. It coerces. And the people of that message do not pretend otherwise.

Revelation closes the canon by sweeping back the veil on a theater where the stakes go cosmic. Seals open and the horsemen ride; trumpets sound and the earth convulses; bowls pour out and the great city is judged; the dragon and the beast gather nations for war; the Rider on the white horse wages a final battle; and the old creation gives way in fire to a new heavens and new earth. There is nothing tepid here. The end of history in Scripture is not a sunset over calm waters; it is a storm that tears down the architecture of defiance and builds a city where tears are finally dried because the causes of tears have been judged and removed. If you recoil at the force of it, you are supposed to. Revelation doesn’t court our sensibilities; it confronts them.

Return to the present and the pattern holds. Nations still arise and fall by force. Laws still encode the interests of the strong and must be contended with by movements that know exposure alone does not topple entrenched power. Nonviolence can reveal, shame, and awaken—and where it has done so, we should acknowledge the courage—but revelation is not removal. Hatred does not vaporize because it is filmed; it adapts to a new costume. Bigotry does not die because it is denounced; it migrates to a new platform. Even within the halls of government—any party, any era—the impulse to dominate, exclude, and punish does not retire; it reorganizes. The slogan “violence is never the answer” functions here as a narcotic for the conscience. It helps us feel virtuous while we avoid accounting for the forces that actually move the world.

So what, then, is the truth that won’t let us go? Violence is not an interruption of history; it is one of its engines. Nonviolence can be a witness, a rebuke, a prophetic exposure of evil; it can change hearts and shift windows of possibility; but it has rarely dethroned powers without some other hand on a lever that bites back. Mankind does not hover above this reality. We are the conduit through which it flows: in families, in tribes, in city gates, in parliaments, in pulpits, in comments sections, in markets, and on borders. We wield it, suffer it, excuse it, and sometimes—when we are honest—admit that what we called “peace” was only a pause between rounds.

Here is the revelation that cracks the slogan in half: we are not here to offer a solution to violence, because, from the very beginning, violence has been the solution. It was the solution in heaven when the dragon was cast out. It was the solution in the flood when a world soaked in blood was washed and the story reset on a narrow plank of mercy. It was the solution at the cross where the worst violence men and powers could devise collided with the body of Yehoshua and, in being spent there, was turned against itself. It is the solution at the end when the Rider breaks the siege and the city descends because the enemies of that city are no more. None of this is an altar to cruelty; it is a confession that the world we inhabit is not re-written by wishes. Forests are not renewed without firebreaks. Tumors are not healed by platitudes but by cuts that bleed. Mountains are not raised without plates that grind and cities that crumble when the earth buckles. Saying “I don’t believe in violence” to a lion is not bravery; it is abdication. Reality will not honor the sentence.

If this sounds brutal, it is because reality is often brutal. If it sounds clarifying, it is because telling the truth is clarifying. The purpose of this deep dive is not to baptize bloodshed or to hand out permission slips for harm. It is to stop lying to ourselves about what has made worlds and unmade them since rebellion cracked the sky. When we name violence as the engine that has driven creation’s judgments, history’s turning points, and our own national and personal crossroads, we do not thereby celebrate it; we take away its favorite hiding place: our denial. And once denial is gone, the choices left to us are at least honest. We can pretend the lion is tame and be devoured while congratulating ourselves for our ideals, or we can admit that from heaven’s first war to the last day’s verdict, violence has been the tool that ends some worlds and begins others. The only question left is whether we will keep mouthing slogans to feel clean or finally reckon with the fire that always has—one way or another—decided what comes next.