Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

To Whom it may concern….

Let’s end the King James–or–nothing fantasy with a clean incision. The claim sounds pious on the surface—cling to one book, one voice, one banner—but underneath it is historical amnesia and theological confusion. God did not wait until 1611 to inspire Himself in English prose. Inspiration happened once, in the tongues He chose—Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek—through the authors He breathed through. Everything after that is transmission and translation. Some of it is excellent, some of it is poor, and some of it is deliberately steered by politics. The King James Version is a literary monument and a cultural force; it is not the moment of inspiration. Treating it as such is not faithfulness; it is idolatry dressed in antique lace.

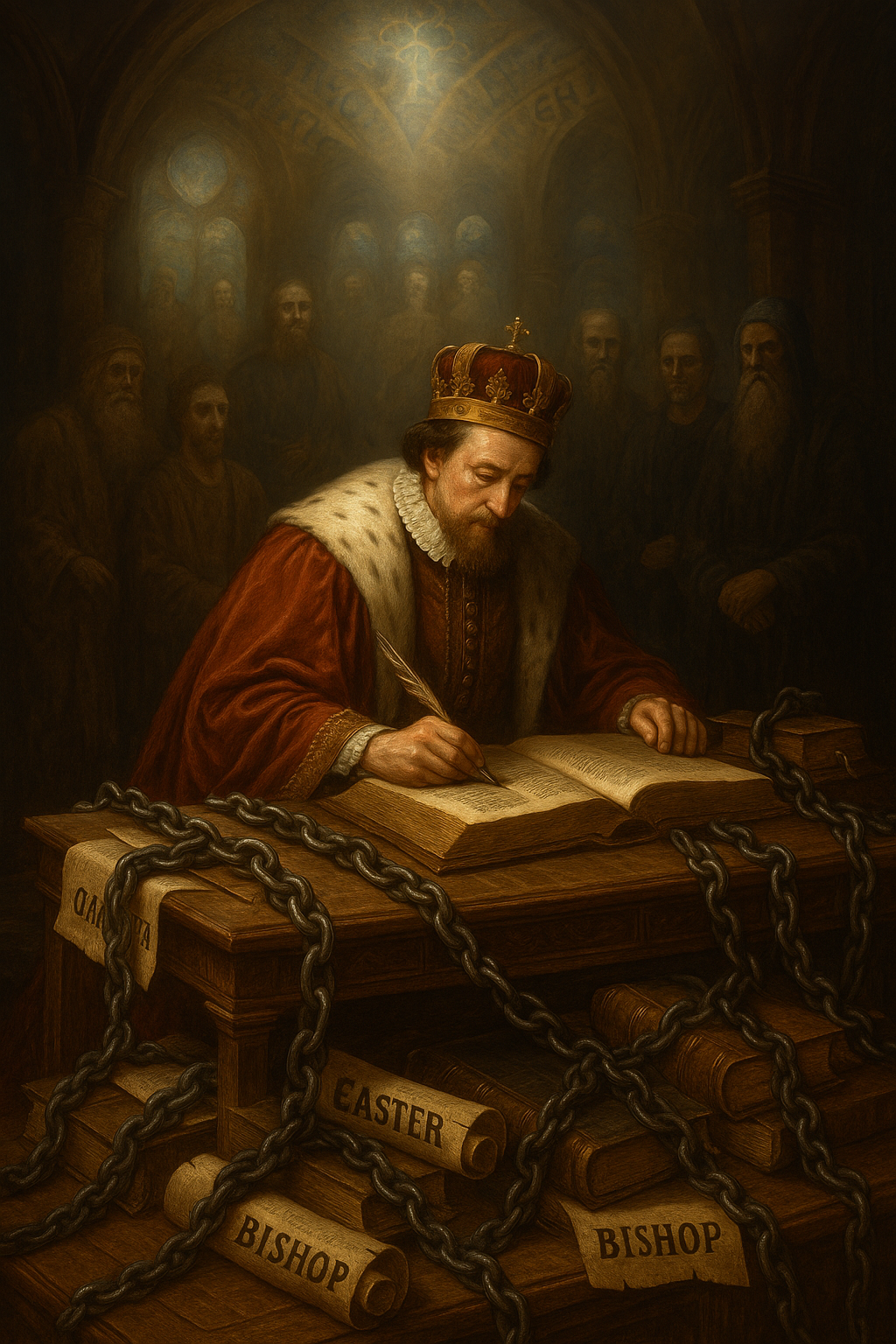

The KJV was born in a storm of politics, not a cloud of glory. In 1604, James I needed religious stability more than he needed philological purity. England was fissured—Anglicans guarding the state church, Puritans pushing for reform, Catholics resisting from the margins. The most popular Bible among commoners, the Geneva Bible, carried marginal notes that did not flatter monarchs or absolutist claims. James hated those notes. His solution was not a prayer meeting but a policy: commission a new translation that would read beautifully in church, strip away incendiary commentary, and harmonize the kingdom around language that affirmed the hierarchy he intended to rule. That is the cradle of the KJV—royal ambition swaddled in scripture.

From the start, the translators were chained to the crown’s rails. James gave them fourteen rules, and those rules mattered. They mandated the Bishops’ Bible as the base text, demanded the retention of “old ecclesiastical words,” discouraged alteration of familiar chapter divisions, forbade marginal notes except for brief lexical glosses, and funneled disagreements up a hierarchy he controlled. That single phrase—“the old ecclesiastical words to be kept”—was not a neutral style guide; it was an ideological brake. It is why the Greek ekklēsia, an assembly of called-out people, became “church,” a term freighted with institutional architecture, clerical garments, and state supervision. It is why episkopos, an overseer who does a function, became “bishop,” a title that cements a rank. The rules guaranteed that the English ecclesial ship would stay on the course set by the crown.

The KJV was not created from virgin cloth but quilted from earlier English work, especially William Tyndale’s luminous phrasing. That is one reason it sounds so majestic. The translators also worked with the manuscripts available to them. For the New Testament that largely meant the Textus Receptus—Erasmus’s printed Greek compiled from a handful of late Byzantine manuscripts, hurriedly edited, sometimes back-translated into Greek from Latin where gaps existed. For the Old Testament it meant the Masoretic tradition they had in hand. None of that is illegitimate; it is simply ordinary historical reality. But ordinary historical reality is a long way from the fantasy that the English wording of 1611 or its later revisions descended untouchable from heaven.

The book that rolled off the presses in 1611 would be unrecognizable to many modern KJV-only advocates. It was set in blackletter type, spelled with seventeenth-century orthography, and it included the Apocrypha between Testaments. Subsequent printings introduced notorious blunders—the “Wicked Bible” left the “not” out of “Thou shalt not commit adultery”—and the text people read today is largely the 1769 Blayney revision, which normalized spelling and punctuation. If a movement insists that God’s perfect English sits in your hand, it must answer a basic question: which English? 1611 with the Apocrypha and “Iesus”? Or 1769 with standardized spelling? Or one of the many nineteenth-century printings with their own sets of minor differences? Idolatry hates this question because idols cannot survive version control.

Where the rules bit, meaning shifted. When Acts uses Pascha, it is Passover; the KJV famously renders it “Easter” in Acts 12:4, baptizing an English church calendar into a Jewish feast’s slot. When Paul writes to “overseers and deacons” at Philippi, the KJV’s “bishops and deacons” relocates the locus of authority in the reader’s mind from function to office. When 1 Corinthians 13 scales the heights of divine nature in agapē, the KJV’s “charity” narrows the horizon toward philanthropy. And when the Greek and Hebrew names carry prophetic weight—Ya‘aqov is Ya‘aqov—the instruction to retain names “as commonly used” severs linguistic sinew to fit English ears and, conveniently, the king’s own name adorns the epistle we still call “James.” None of these choices are random. They are the predictable fruit of a project designed to be beautiful, public, and safe for a monarchy.

This is why the numerology crowd goes off the rails in English. Hebrew letters carry numbers, and the biblical authors sometimes weave numerical symmetry into the warp and woof of the text. Greek, too, participates in isopsephy. The patterns live in the languages of inspiration. English does not naturally carry those numeric signatures, and when it seems to, it is usually the echo of translation choices or the pareidolia of the reader. If someone claims that the English words of the KJV hide a perfect lattice of “seventy times seven,” the sober response is simple: you are measuring the seam allowances of a quilt and calling them original cloth. You may find symmetry; you are not therefore touching inspiration. God’s fingerprints are on the Hebrew and Greek; English patterns are often the shadow-play of human stitching.

Why do people refuse to see this? Because tradition is warm, and truth is cold before it is fire. Because cognitive dissonance is painful; if they admit the KJV is a brilliant but bounded translation, they must reevaluate sermons, habits, and slogans that have defined their religious lives. Because an English-only faith is effortless and expertise in original languages is costly. Because there is a narcotic sweetness to in-group certainty—the pride of possessing “the one true Bible” while others are “deceived.” Because pulpits have trained generations to confuse questioning a translation with questioning God, turning loyalty to a version into a test of orthodoxy. And because numerological sleight-of-hand feels like revelation without repentance: a code to crack rather than a cross to carry.

None of this demeans the KJV’s accomplishments. It is one of the most beautiful works ever penned in English. It has carried truth to countless ears, shaped literature for centuries, and given us phrases that sing—“Let there be light,” “In the beginning was the Word,” “the powers that be.” But beauty and usefulness are not the same as exclusivity and inerrancy. The KJV’s authority is historical and literary; the Scriptures’ authority is divine and linguistic at the point of origin. Confusing those categories turns a translation into an idol and mutes the living voice of the text God actually breathed.

If the goal is fidelity to Yahweh, the path is obvious. Go to the source. Treat the inspired text as the inspired text—Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek—and let every translation, including the KJV, sit under the scrutiny of the originals. Let ekklēsia be an assembly, not a building. Let episkopos be an overseer who serves, not a throne to occupy. Let Pascha be Passover, and let the calendar bow to the text, not the text to the calendar. Let Ya‘aqov be Ya‘aqov unless the argument compels otherwise, not because the king’s ear preferred a different syllable. Where English cannot carry the full freight of meaning, note it honestly; where it can, rejoice in it. Use the best tools—lexicons like HALOT and BDAG, interlinears, critical editions—and keep the humility to correct yourself when the source demands it.

The “KJV-only” posture is a fortress built on the authority of a monarch, the inertia of tradition, and the romance of English cadence. It is not a sanctuary built on the inspiration of Yahweh. The fortress looks sturdy until you test its stones: the rules that constrained it, the manuscripts that limited it, the revisions that altered it, the choices that tilted it toward hierarchy, the calendar swap that repainted a feast, the lexical decisions that narrowed divine love. Once you see the masonry, the spell breaks. And that is a mercy, not a loss. When the idol falls, the Word stands taller.

So here is the clean conclusion. Yahweh inspired His Word once, through His chosen authors, in the languages He chose. The King James Version is a remarkable English witness to that Word, but it is still a witness—contingent, situated, and sometimes skewed by the hand that commissioned it. Hunt your numbers and your patterns where Yahweh placed them, in the Hebrew and Greek, and let every English rendering—KJV included—be tested by the source. If you do that, you honor the God who speaks, rather than the king who set the rules. And you trade the comfort of a man-made fortress for the freedom of standing in the open air of what Yehoshua actually said.