Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

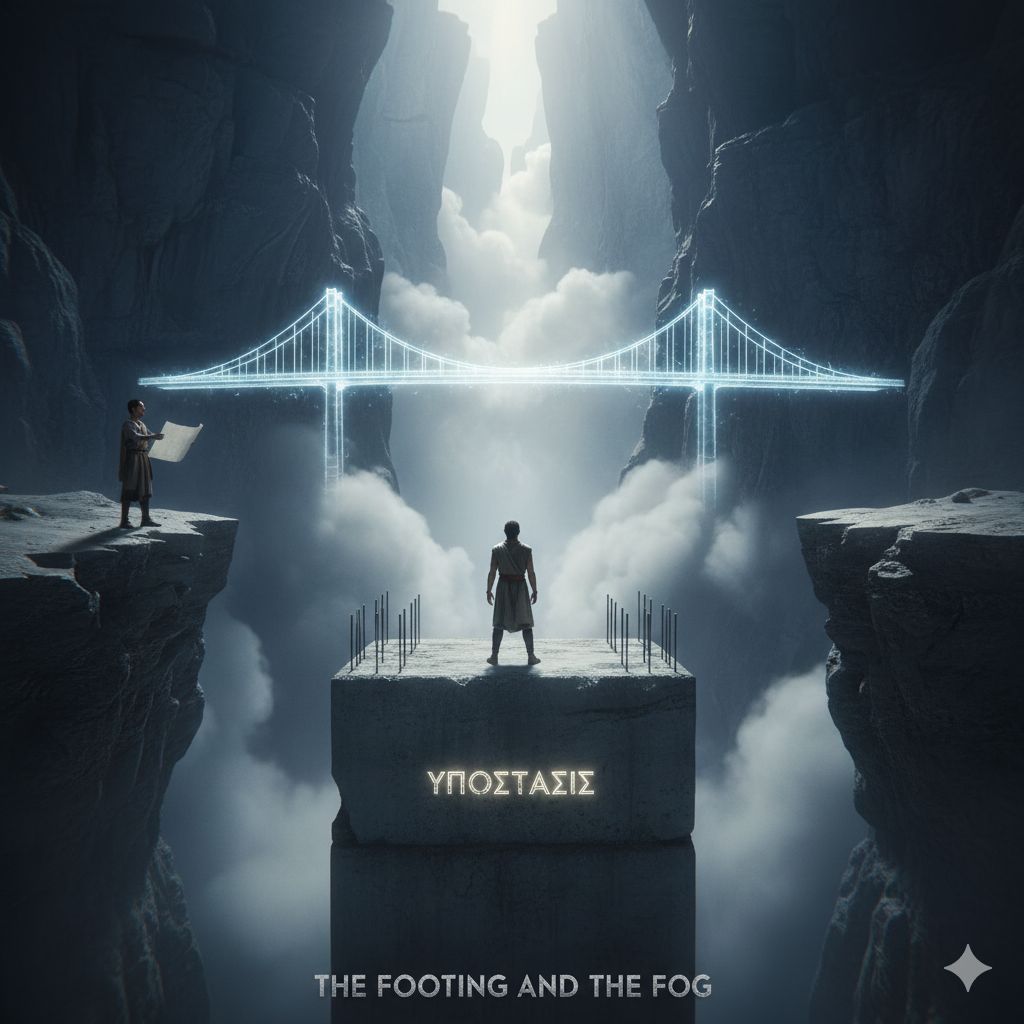

There comes a point where language itself must be put on trial. Hebrews 11:1 stands as one of those threshold verses where the entire architecture of covenant either holds or collapses, not because the text is weak, but because the translation has replaced structural trust with mental belief and then called the mixture “faith.” This is not a poetic problem. This is a load‑bearing problem. A bridge that was designed to rest on concrete footings has been reimagined as resting on fog, and generations have been taught to step forward as though mist and granite were the same kind of ground. Hebrews 11:1 does not define a private inner opinion about God. It defines a trust‑bond, a trust‑stance, a covenantal footing upon which God Himself builds. The verse exposes, with surgical clarity, the difference between belief and trust, between assumption and stance, between thought and foundation. And once that structure is seen, it becomes impossible to return to the illusion that belief at all, is what the New Testament is demanding.

At the smallest level, the distinction begins with belief and trust. Belief is mental, internal, conceptual, and assumptive. It exists in the mind as an idea, a conclusion, an internal narrative about what might be true. Belief is like a sketch made in pencil. It can be altered, erased, redrawn, second‑guessed. A person can examine a belief from a distance and say, “Perhaps,” “Maybe,” or “I used to think.” Belief can be adopted in a moment and abandoned in another. In Scripture and in lived reality, belief belongs to the realm of thought. It is a thought, nothing more and nothing less. And thoughts, by nature, are light, movable, and subject to revision. One can question belief without any immediate consequence to physical posture or embodied stance.

Trust, by contrast, is structural, relational, load‑bearing, covenantal. Trust does not live merely in the mind; it lives in the body, in decisions, in alignment, in concrete action. Trust is like stepping onto a beam suspended over a canyon and letting full weight rest upon it. The question is no longer “What do you think about the beam?” but “Are you standing on it?” Trust is what a person does with their weight, their risk, their future, their obedience. Trust is a bond between persons, not a solitary concept inside a skull. Trust can be described as the architecture of relationship where one party leans, and the other bears. In Scripture, trust is not merely a psychological state; it is a covenantal reality in which God binds Himself to respond to a stance, not to a concept. Trust carries weight. Trust responds to actual danger. Trust is willing to stand where the ground is either solid or not, and the only proof is the act of standing. Evetime in compromised English where the Bible says belief, have faith, through faith and so on, the Greek word used is “pistis” (trust, stance, position, foundation) or “pisteuo.” (to trust, to rely upon)

Because of this, there is a simple but devastating axiom: you can question belief; you do not question trust. When someone says, “I trusted and then I questioned whether I should trust,” the moment of questioning reveals that trust has already weakened, sliding back into the category of thought. True trust, in its covenantal sense, stands (as if on a foundation or is the foundation). It may tremble, but it does not treat the footing as optional. Belief can remain in the realm of “I wonder” forever and never descend into risk. Trust does not stay at that altitude. Trust steps. Belief talks about the bridge; trust walks across it.

This distinction continues with assumption and stance. Assumption is an imagined foundation. It feels like ground, but it has never been tested. Assumption is a floor drawn on a wall in perfect perspective; it looks walkable until someone tries to step. People live in assumption when they treat untested ideas as if they were stone. Assumption can be formed from tradition, from culture, from hearsay, from partial readings of Scripture, from denominational habits. Assumption feels like “of course,” but it has never carried weight through trial. A person cannot truly stand in an assumption because standing, in the covenantal sense, requires resistance, pressure, and endurance.

Stance, by contrast, is an actual foundation. Stance is where the body is placed, where decisions land, where consequences begin. Stance can be measured by where the feet are, what is risked, what is refused, what is obeyed. There is a qualitative difference between saying “I think this is right” and planting the feet in that position when everything pushes the other way. Stance is not merely cognitive consent; it is positional fidelity. One can stand in a stance. One cannot stand in an assumption. Assumption has never been poured like concrete. It has never been tested under the weight of time and resistance. Stance is the place of covenantal exposure, where the reality of the foundation is revealed.

From this vantage point, thought versus foundation comes into sharp focus. Belief is a thought. This does not demean belief; it simply locates it. It lives in the cognitive realm, in the genuine or mistaken conviction that something is true. Trust, however, is a foundation. Trust is what the entire structure of obedience, hope, endurance, and covenantal partnership rests upon. Trust can be described as ground, footing, bedrock. A building blueprint may assume the ground will hold, but until the concrete is poured and the structure stands, all drawings remain in the realm of thought. In the same way, belief can draw the lines of theory, but trust is what happens when the footings go into the earth and the weight of the structure presses down.

Hebrews 11:1 becomes the central verse where all these distinctions converge. The Greek sentence usually translated “faith” is not an abstraction about a religious feeling. It is a definition of pistis as trust‑bond, trust‑stance. The standard English “faith” text reads: “Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen” (Hebrews 11:1, NASB). But this rendering has been shaped by centuries of doctrinal overlay, where “faith” has migrated into the realm of mental belief, doctrinal assent, and internal persuasion. The Greek term pistis does not belong naturally in that category. It belongs in the structural, covenantal, relational world of trust.

A literal interlinear view begins to restore this architecture. The Greek text reads:

Original: Πίστις δέ ἐστιν ἐλπιζομένων ὑπόστασις, πραγμάτων ἔλεγχος οὐ βλεπομένων. Transliteration: Pistis de estin elpizomenōn hypostasis, pragmatōn elegchos ou blepomenōn. Literal Meaning: Trust‑bond now is the sub‑standing of the hoped‑for things, the exposure‑proof of realities not being seen.

The first term, Πίστις (Pistis), is usually glossed in institutional lexicons as “faith, trust, belief, trustworthiness.” BDAG and similar tools tend to keep the term in a flexible semantic field that allows traditional theology to pour doctrinal “faith” back into the word. In practice, this has produced a blended concept where belief, trust, doctrine, and religion are fused under one English label. But at the covenantal level, pistis is not a vague internal attitude; it is fidelity, loyalty, trust‑bond, and trust‑stance. It describes the relational footing upon which God and His people interact.

The second key word is ὑπόστασις (hypostasis). BDAG and standard lexicons often render it as “assurance, confidence, substance,” leaving the English translator free to choose a term that fits established theology. Yet the literal formation of the word matters: hypo (under) + stasis (standing). The word is structurally charged: under‑standing, sub‑standing, that which stands under as footing. In ancient usage, ὑπόστασις can refer to a foundation, a substantial reality underlying what is visible, a title‑deed or guarantee. In covenantal architecture, hypostasis is not a feeling of confidence; it is the footing under hope. The NASB’s “assurance” shifts the focus from concrete footing to psychological state. The Greek forces the opposite: the term names what lies under, carrying weight.

The third key word, ἔλεγχος (elegchos), is often translated “conviction” or “evidence.” BDAG places it in the semantic range of “proof, evidence, conviction, reproof.” The word carries the notion of exposing something to light, bringing it under examination, making it manifest as real. In covenantal context, elegchos is proof‑exposure, the way unseen realities are shown to be actual through trust‑anchored action and outcome. The NASB’s “conviction” again internalizes the reality, treating it as inner certainty rather than external proof that can be examined.

Thus, the triadic comparison for Hebrews 11:1 stands as follows:

Literal Interlinear (Covenantal): Trust‑bond now is the under‑standing (footing) of the hoped‑for things, the proof‑exposure of realities not being seen.

BDAG Parsing (Institutional): Faith (as trust/confidence/belief) is the assurance (confidence) of what is hoped, the conviction (inner persuasion) about things not seen.

NASB (Compromised Translation): Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.

The literal interlinear exposes pistis as trust‑bond, not floating belief; hypostasis as footing, not inner assurance; elegchos as proof‑exposure, not merely internal conviction. When these words are allowed to retain their structural meanings, Hebrews 11:1 emerges not as a verse about psychological certainty but as a verse about covenantal architecture.

Within this verse, pistis performs two functions. First, trust is the foundation of what is hoped. Hope in Scripture is not wishful thinking; it is confident expectation anchored in the character and promises of Elohim (Eh‑lo‑HEEM) — God. Yet hope, by itself, is forward‑facing. It looks toward what is not yet. Trust is what bridges the gap between present stance and future fulfillment. Trust is the footing of what is hoped. A person who “hopes” but refuses to stand, act, or align has not yet engaged in pistis. Trust undergirds hope like a foundation under a yet‑unbuilt structure. In Romans 4, Avraham (Ahv‑rah‑HAHM) — Abraham — is described as one who “in hope against hope believed” (Romans 4:18, NASB), yet his trust is demonstrated not in mental certainty alone but in obedience, in leaving his land, in offering Yitsḥaq (Yeets‑KHAHK) — Isaac — on the altar. The hope is future; the trust is present stance.

Second, trust is the proof‑exposure of what is unseen. The unseen realities of God’s kingdom are not proven true by mental insistence. They are made visible through trust‑anchored action and divine response. When Noaḥ (NO‑akh) — Noah — builds an ark in response to a word about unseen judgment, his trust creates a platform upon which the unseen reality of God’s warning becomes manifest in time (Hebrews 11:7, NASB). The action of trust exposes the unseen as real. When Ḥannah (KHAH‑nah) — Hannah — pours out her soul before YHWH and then walks away no longer sad before she conceives Shemu’el (Sheh‑moo‑EL) — Samuel (1 Samuel 1, NASB), her trust‑stance exposes the unseen faithfulness of God as operative in her barren circumstances. Trust functions as the evidentiary bridge between invisible promise and visible outcome.

Belief collapses under this architecture. Belief cannot be the foundation of what is hoped because belief remains in the mind. Belief can affirm that something will happen, but it does not, by itself, place weight on the promise. Belief cannot be proof because proof requires something that can be examined beyond the interior of the believer. Belief is too unstable to support hope when the winds of delay, disappointment, and contradiction arise. In Ya‘aqov (Yah‑ah‑KOVE) — James — the demons are said to “believe” and shudder (James 2:19, NASB). They possess accurate belief about the reality of God, but this belief is not trust; it is not covenantal alignment. Their belief cannot function as foundation or proof. It recognizes reality without resting in it.

Belief cannot bear weight. When belief is treated as a load‑bearing structure, it turns spiritual life into constant strain. The believer is told to generate more belief, to “have more faith,” as if mental intensity could substitute for footing. But a thought, no matter how fervent, is not a foundation. Under trial, belief alone fractures, rearranges, or is replaced. Belief is collapsible because it never was poured into the ground as concrete in the first place. It was a design sketch treated as physical steel. Hebrews 11:1 does not allow belief to occupy the position of hypostasis. The verse demands footing, not fervor.

Trust, on the other hand, fits the architecture exactly. Trust is load‑bearing. Trust can carry the weight of hope because trust expresses itself in alignment, obedience, and staying put when contrary evidence screams “Leave.” Trust is structural because it participates in God’s own faithfulness. Where belief says “I think God is faithful,” trust rests its weight upon that faithfulness in specific, costly, and persistent ways. Trust is covenantal because it is not merely directed toward a proposition but toward a Person. Trust is something Elohim can build on. A life arranged in trust‑stance becomes a platform where God’s actions in history can land.

This is why Hebrews 11 unfolds as a gallery of trust‑stance, not mental belief. Each example in the chapter begins with “By faith” in the NASB, yet every story describes concrete steps, decisions, and stances taken on the basis of God’s word. Havel (HAH‑vel) — Abel — offers a better sacrifice (Hebrews 11:4). Ḥanokh (KHAH‑nokh) — Enoch — walks with God and is taken (Hebrews 11:5). Noaḥ builds an ark (Hebrews 11:7). Avraham goes out not knowing where he is going (Hebrews 11:8). Sarah (SAH‑rah) receives power to conceive (Hebrews 11:11). Mosheh (MOH‑sheh) — Moses — refuses to be called the son of Pharaoh’s daughter and chooses ill‑treatment with the people of God (Hebrews 11:24‑25). None of these accounts stop at belief. Every one is a trust‑stance bearing weight, becoming foundation and proof.

At the covenantal level, trust creates a platform for God to build on. Trust is the footing; God is the builder. Trust is to the life of a believer what bedrock is to a tower. The builder does not rest beams directly on topsoil; the beams rest on pilings that go down to solid ground. In the same way, God does not rest His promises on the loose sand of fluctuating mental assent. He binds Himself to stances that align with His word. This is visible in the life of Avraham, where trust is “credited to him as righteousness” (Genesis 15:6, NASB; echoed in Romans 4:3). The Hebrew text says:

Original: וְהֶאֱמִן בַּיהוָה וַיַּחְשְׁבֶהָ לּוֹ צְדָקָה Transliteration: Vehe’emin ba‑YHWH vayachsheveha lo tsedaqah. Literal Meaning: And he trusted in YHWH, and He accounted it to him as covenant‑rightness.

The institutional reading treats this as belief being credited. But the root ’aman in this form (he’emin) is not a thin mental nod. It carries the sense of steadying oneself on, leaning into, relying upon. Avraham’s stance becomes a footing upon which God establishes a covenantal relationship; from that point, God builds generations, land promises, and messianic lineage on that trust‑stance.

Trust is also the only thing that activates movement in the covenantal sense. Belief does not move God. Belief describes; trust participates. Belief does not fuel anything beyond psychological experience, but trust becomes the positional condition for divine action. Consider the healings in the life of Yehoshua (Yeho‑SHOO‑ah). When the woman with the hemorrhage touches the fringe of His garment, Yehoshua says, “Daughter, take courage; your faith has made you well” (Matthew 9:22, NASB). The Greek reads:

Original: Θάρσει, θύγατερ· ἡ πίστις σου σέσωκέν σε. Transliteration: Tharsei, thygater; hē pistis sou sesōken se. Literal Meaning: Take heart, daughter; your trust‑bond has delivered you.

Her healing is not described as an outcome of correct doctrine about Yehoshua. It is anchored in a trust‑stance expressed in action: pressing through the crowd, touching His garment, risking social and religious violation. Her movement exposes her stance. That stance is what Yehoshua names as pistis. Belief alone would have been content to think “He can heal me” and remain on the edge. Trust steps forward and touches. The movement of God in response is tied to trust‑stance, not to bare cognitive belief.

Trust is simultaneously foundation and evidence. It supports what is hoped and exposes what is unseen as real. When trust takes a stance, it creates a moment in time where unseen realities can become visible through outcome. The unseen promise of God is tested against the footing of trust. If the outcome aligns with the promise, trust becomes proof‑exposure to all watching. This is why the apostles later speak of “the tested genuineness of your faith” (1 Peter 1:7, NASB). The Greek word there for “tested genuineness” (dokimion) carries the sense of metal tested by fire and shown to be real. The testing of trust does not occur in the brain alone; it occurs in lived stance. The fire does not test beliefs on a page; it tests the structure built on trust. Foundation and evidence thus converge in the same covenantal reality: pistis as trust‑stance.

Trust, then, is covenantal alignment. It is relational fidelity, alignment with God’s nature, participation in God’s action, and the platform of divine partnership. Trust is not arbitrary risk; it is risk anchored in the character and word of Elohim. When a person stands in trust, they align with who He is. This is why Habbaquq (Khah‑bah‑KOOK) — Habakkuk — records, “But the righteous will live by his faith” (Habakkuk 2:4, NASB). The Hebrew reads:

Original: וְצַדִּיק בֶּאֱמוּנָתוֹ יִחְיֶה Transliteration: Ve‑tsaddiq be’emunato yichyeh. Literal Meaning: But the righteous one by his trustworthiness/steadfast trust will live.

Here, emunah is not a ghostly feeling. It is steadfastness, fidelity, reliability. The righteous live by trust‑stance, by covenantal steadiness aligned with YHWH. Sha’ul (Shah‑OOL) — Paul — lifts this text into Romans 1:17 and Galatians 3:11, but when “faith” is interpreted as mental belief, the entire dynamic is inverted. The original architecture insists that life flows along the line of trust, not mere opinion.

Into this unveiled architecture comes the collapse from trust to belief. The original movement was from position to assumption, from trust to belief, from foundation to imagination. Position describes an actual stance in relation to God’s word and character. Assumption describes a mental posture that has never borne weight. Trust describes the concrete alignment of life with God’s speaking. Belief describes a mental conclusion about God. Foundation describes what stands under. Imagination describes what lives only in the mind. When the New Testament pistis was translated into an English “faith” that mixes trust and belief, the structure shifted. The community moved from position to assumption, from trust‑stance to belief‑concept.

In real world terms, when a person moves from position to assumption, their trust‑stance collapses into belief, hidden beneath the mask of what English calls faith. Outwardly, the language remains: talk of “having faith,” “keeping the faith,” “believing God.” But the internal architecture has changed. Instead of actual stances grounded in obedient trust, there is a set of religious assumptions about God’s nature that never step into risk. Their trust becomes belief the moment they leave her stance and steps into assumption, all of it disguised under the word faith. In relationships, this is like a marriage where the vows remain on paper, but the actual daily stances of fidelity are abandoned. The couple continues to call the arrangement “marriage,” but the lived covenant is gone. The label covers collapse.

The foolproof clause reveals why trust and belief cannot be the same. The axiom stands: you cannot stand on something you question. Trust, by definition, is unquestioned stance at the moment of standing. This does not mean trust never wrestles beforehand, but when the stance is taken, the footing is treated as reliable. Belief, however, is questioned thought. Thought is the arena where questions circulate freely. This is healthy and necessary for discernment, but it also means belief, as thought, is not the same as the footing upon which someone stands. Trust is load‑bearing; belief is collapsible. Trust is foundation; belief is imagination. To treat them as synonyms is to erase the very distinction Hebrews 11:1 exposes.

Trust and belief cannot be interchangeable. They cannot occupy the same sentence without distortion when the sentence is defining the covenantal mechanism of how God engages His people. The English word “faith” masks this difference, creating the illusion that belief is enough to stand on. When “faith” is preached as mental certainty, people are taught to strain to believe harder rather than to stand differently. The result is a Christianity that talks about foundation while standing on fog. The doctrine may sound strong, but the structure remains weak because no footing has been poured.

At the macro level, the English word “faith” is a mixture. English has fused belief, trust, doctrine, and religion into a single religious term. “Faith” can mean “what one believes,” “the doctrines of a denomination,” “a personal posture of trust,” or “the religion itself.” In common speech, people say “the Christian faith,” “people of faith,” “keep the faith,” “statement of faith.” Each usage pulls the word in a different direction. Greek pistis does not do this. It is not a bucket for all religious content. It is a covenantal term bound to trust, fidelity, loyalty, and reliability.

Mixing belief and trust in the term “faith” is like mixing alcohol and water. Once blended, the distinctive properties cannot be easily separated by casual observation. The categories dissolve, and identity is lost. A person may drink the mixture and feel its effect without understanding which component is driving which consequence. In the same way, sermons about “faith” may produce emotional responses, mental assent, and even occasional acts of obedience, but without a clear distinction between belief and trust, the covenantal architecture remains blurred. Hebrews 11:1 becomes a slogan rather than a structural diagram.

The New Testament, however, is trust‑based, not belief‑based. Every major “faith” passage is about trust‑stance. When Yehoshua speaks of “your faith has made you well” (Matthew 9:22; Mark 5:34; Luke 7:50, NASB), He is not commending doctrinal precision; He is acknowledging trust‑stance. When Sha’ul writes that “we walk by faith, not by sight” (2 Corinthians 5:7, NASB), the Greek term pistis describes a mode of walking that rests on God’s unseen promise as solid as visible ground. Early believers lived by trust‑stance. Their allegiance was not to an idea about Mashiaḥ (Mah‑SHEE‑akh) — Messiah — alone, but to the Person and lordship of Yehoshua, expressed in costly loyalty under pressure.

Western theology, over time, replaced trust with belief. Creeds, confessions, and doctrinal statements became the primary markers of “faith.” To “keep the faith” came to mean “hold to the right beliefs” rather than “remain in trust‑stance under pressure.” This shift created a foundationless Christianity, where mental assent to orthodox statements is treated as equivalent to covenantal footing. The epistle of Ya‘aqov protests against this when it insists that “faith without works is dead” (James 2:17, NASB). The text does not add works as a legalistic supplement; it exposes that what is called “faith” without corresponding stance is not pistis at all. Trust without embodiment does not exist.

Hebrews 11:1 is the key that unlocks everything because it defines pistis, defines the foundation, defines the mechanics of hope, defines the structure of unseen realities, and defines how God builds with His people. By placing pistis in direct apposition with hypostasis and elegchos, the verse anchors “faith” as footing and proof‑exposure, not as floating inner persuasion. This aligns with the broader witness of Scripture where trust, not bare belief, is tied to righteousness, deliverance, and covenant life. The righteous live by trust‑stance (Habakkuk 2:4). Avraham is counted righteous by trust‑stance (Genesis 15:6; Romans 4). Yisra’el (Yis‑rah‑EL) — Israel — falls in the wilderness for lack of trust, not for lack of awareness (Hebrews 3:19, NASB: “So we see that they were not able to enter because of unbelief,” where “unbelief” is apistia, lack of trust‑bond).

The insight that distinguishes belief from trust restores the original architecture. Trust is foundation. Trust is proof. Trust is stance. Trust is covenantal alignment. Trust is the platform of divine action. Belief never had the power to do any of that. Belief can describe; only trust can bear. Belief can admire; only trust can obey. Belief can outline blueprints; only trust can pour concrete and raise beams. The New Testament calls for pistis in this latter sense.

The conclusion, then, is not a minor adjustment in vocabulary but a structural recalibration of what it means to stand before God. Hebrews 11:1, read through the lens of literal interlinear translation, reveals a covenantal mechanism that has been obscured by blended English “faith.” Pistis is not mental belief wrapped in religious language. It is trust‑bond, trust‑stance, the load‑bearing alignment of a life with the speaking and character of Elohim. Hypostasis is not a private feeling of assurance; it is under‑standing, the actual footing beneath hope. Elegchos is not mere internal conviction; it is proof‑exposure, the way unseen realities are made visible through trust‑anchored action and divine response.

Once this architecture is restored, the call of the New Testament becomes clear. The summons is not to strain for more intense beliefs but to take actual stances that align with the voice and nature of God. The life built on belief alone will always shake under the weight of trial, because thought cannot carry what only trust can bear. But the life built on trust‑stance becomes a living exposition of unseen realities, a platform on which God Himself delights to build. In that life, Hebrews 11:1 is no longer a slogan recited; it is a structure inhabited. And in that structure, the illusion that belief is enough to stand on finally gives way to the solid ground of covenantal trust.