Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

With Michael Walker

With Michael Walker

To Whom it may concern…..

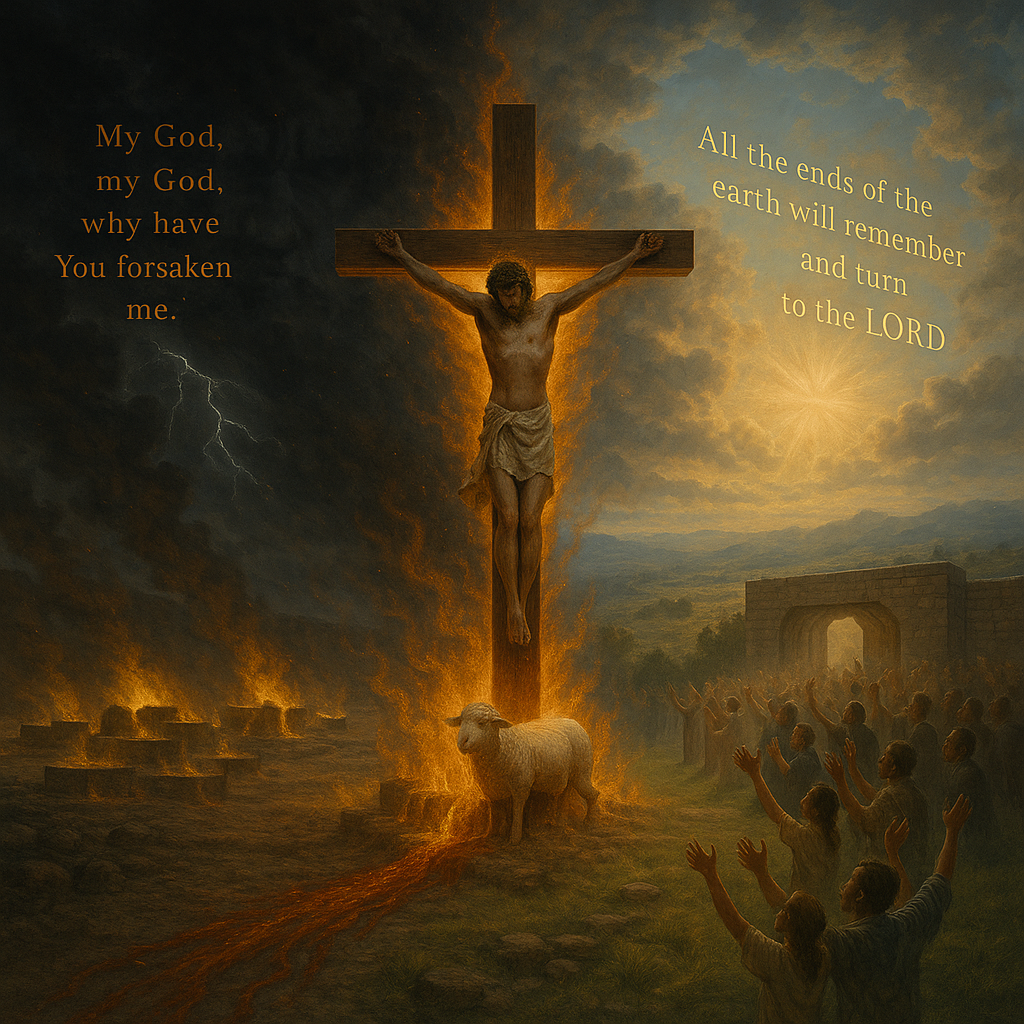

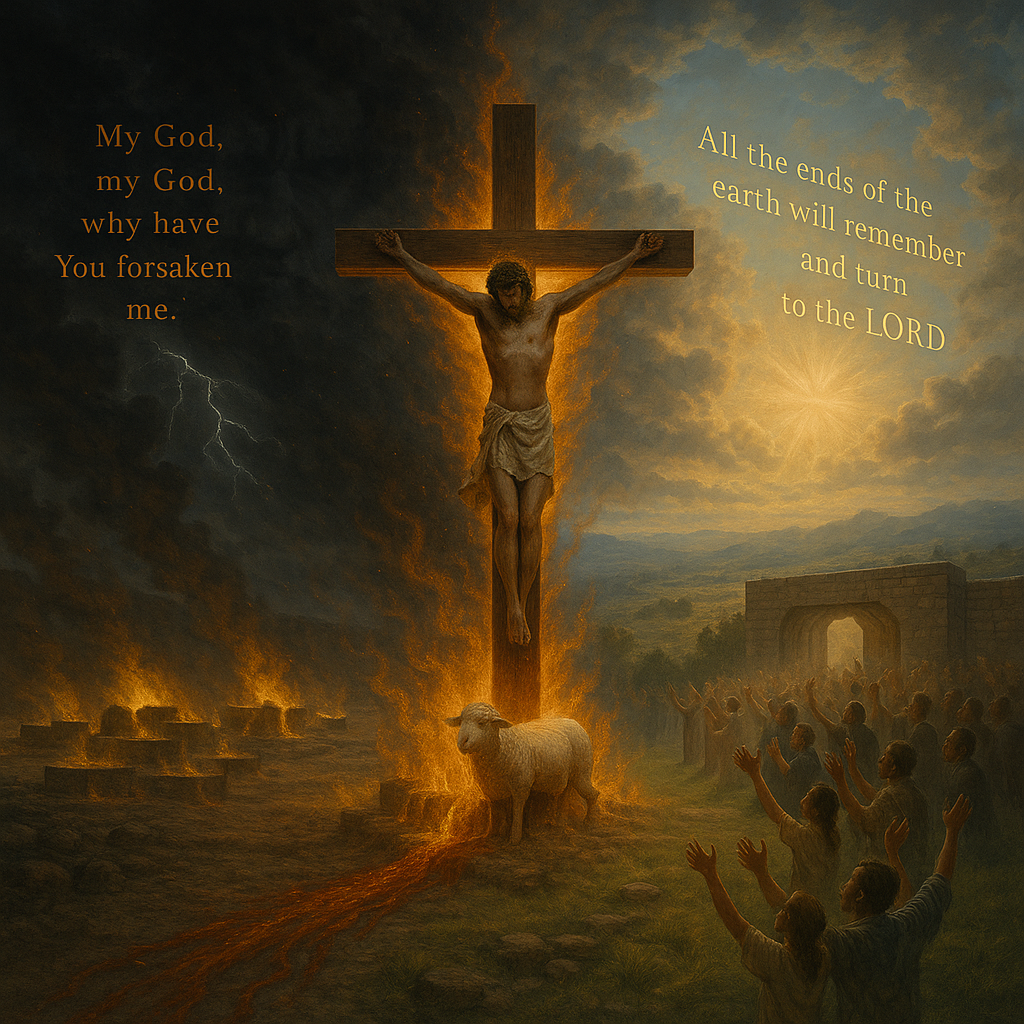

The modern confusion about the Messiah’s cry from the cross, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me,” is rooted in a sentimental pseudo-theology that has plagued much of the church for generations. Many people, desiring to soften the sharp edge of the cross, insist that God was never truly separate from the Son, that wrath was somehow mingled with intimacy, that in pouring judgment He was at the same time whispering comfort. This is the “sentimentalness” of man that tries to tame the horror of Calvary and reshape it into a picture that makes sense to human emotion. But this is not what the Word of God teaches. Scripture is unflinching in its declaration: when Yahweh pours out wrath, He withdraws His favor, He hides His face, He forsakes, He casts out. The altar, the prophets, the psalms, the cross itself all agree with one voice—wrath means separation, and reconciliation is granted only to those who benefit from the sacrifice, not to the sacrifice itself. To pretend otherwise is to misrepresent the truth of God’s Word and rob the cross of its terrible beauty.

First, we must understand the language the Bible itself uses. Yahweh is holy, which means He is utterly separate from sin. Leviticus 11:44 says, “Be holy, for I am holy.” Psalm 5:4–5 declares, “For You are not a God who takes pleasure in wickedness; no evil dwells with You. The boastful shall not stand before Your eyes; You hate all who do iniquity.” Habakkuk 1:13 adds, “Your eyes are too pure to approve evil, and You cannot look on wickedness with favor.” Holiness means distance from sin, not nearness. To bear sin is to bear separation. Alongside holiness is the theme of wrath, curse, and the face of God. Wrath is His settled opposition to sin, not an arbitrary flare of anger but the consuming fire of His holiness. To have His “face” shine is to have His presence and blessing; to have His face hidden is to be cast into judgment. Numbers 6:24–26 is the priestly blessing of His face shining, while Deuteronomy 31:17–18 declares that when wrath falls, He will hide His face and forsake. Psalm 34:16 proclaims, “The face of Yahweh is against evildoers.” These are not metaphors of intimacy; they are declarations of separation. Even in the New Testament, wrath is a category of distance: Romans 1:18 says the wrath of God is revealed from heaven against all ungodliness, John 3:36 says the wrath of God abides on the unbeliever, and Ephesians 2:3 says we were by nature children of wrath.

This separation is baked into the very structure of the altar system in Torah. Every sacrifice offered in Leviticus 1–7 shows the same pattern: the worshiper places his hands on the animal’s head, symbolically transferring guilt, and then the animal is slaughtered. Leviticus 1:4 says, “He shall lay his hand on the head of the burnt offering, that it may be accepted for him to make atonement on his behalf.” The worshiper receives forgiveness and nearness, but the animal bears the death. The blood is poured out and applied because “the life of the flesh is in the blood, and I have given it to you on the altar to make atonement for your souls” (Lev 17:11). The fire of the altar is perpetual, Leviticus 6:12–13, a constant reminder that wrath consumes day and night. The aroma of the offering is pleasing not because the victim is comforted, but because the worshiper is reconciled. This logic continues through the sin offerings and guilt offerings: the sinner is forgiven, but the substitute is slain.

The Day of Atonement in Leviticus 16 illustrates the principle even more sharply. One goat is slaughtered and its blood taken into the Holy of Holies for atonement. Another goat, the scapegoat, bears the sins of the people and is sent away into a solitary land, cut off from the camp. The carcasses of sin offerings are burned outside the camp (Lev 16:27), a picture of exclusion from Yahweh’s presence. Hebrews 13:11–13 explicitly applies this logic to Yehoshua: “For the bodies of those animals whose blood is brought into the holy place by the high priest as an offering for sin, are burned outside the camp. Therefore Yehoshua also, that He might sanctify the people through His own blood, suffered outside the gate. So, let us go out to Him outside the camp.” The Messiah’s death is not pictured as intimacy but as exclusion.

This separation is not an isolated idea; it is a drumbeat through all of Scripture. Isaiah 59:2 says, “Your iniquities have made a separation between you and your God, and your sins have hidden His face from you so that He does not hear.” Deuteronomy 31:17–18 says, “Then My anger will be kindled against them in that day, and I will forsake them and hide My face from them.” Micah 3:4 echoes, “Then they will cry out to Yahweh, but He will not answer them. Instead, He will hide His face from them at that time because they have practiced evil deeds.” Proverbs 15:29 says, “Yahweh is far from the wicked, but He hears the prayer of the righteous.” Psalm 66:18 says, “If I regard wickedness in my heart, the Lord will not hear.” Isaiah 1:15 adds, “When you spread out your hands in prayer, I will hide My eyes from you; yes, even though you multiply prayers, I will not listen.” The pattern is undeniable: sin creates distance, separation, hidden face, wrath, exclusion. That is the condition the Messiah willingly stepped into on the cross.

Psalm 22 is the Spirit-given lens for understanding the cry. The opening line is, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Ps 22:1), which Yehoshua Himself cried in Matthew 27:46 and Mark 15:34. This is not poetic drama; it is lived reality. Psalm 22 details the crucifixion: mocking enemies (22:7–8), hands and feet pierced (22:16), lots cast for garments (22:18). It begins with forsakenness, with silence, with divine absence. Yet it moves through to vindication: “You have answered me” (22:21), “He has not hidden His face from him, but when he cried to Him for help, He heard” (22:24). The psalm closes with global reconciliation: “All the ends of the earth will remember and turn to Yahweh” (22:27). This is the paradox in one psalm—real forsakenness, followed by real vindication, issuing in worldwide salvation. To deny the forsakenness is to flatten the psalm and ignore the cry.

The New Testament confirms this altar logic. Yehoshua was made sin and curse. Second Corinthians 5:21 says, “He made Him who knew no sin to be sin on our behalf.” Galatians 3:13 says, “Messiah redeemed us from the curse of the Law, having become a curse for us.” Romans 8:3 says, “God sent His own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh and as an offering for sin, He condemned sin in the flesh.” He bore the wrath in our place. Romans 3:25 calls Him the propitiation—wrath-absorbing sacrifice. First John 2:2 and 4:10 use the same word: He is the propitiation for our sins, the one who turns wrath away. Hebrews 9 and 10 describe Him entering once-for-all with His blood, securing eternal redemption, offering Himself without blemish, sanctifying us forever. This is not cozy intimacy in wrath; it is judicial substitution.

The signs at Golgotha confirmed it. Darkness fell at noon (Matt 27:45), echoing Amos 8:9 where Yahweh says He will darken the earth in broad daylight as a sign of judgment. The cry of dereliction followed (Matt 27:46; Mark 15:34). Hebrews 13:12 says He suffered outside the gate, in the place of exclusion. John 19:30 records Him saying, “It is finished,” meaning the debt was paid in full, as Colossians 2:14–15 explains: the certificate of debt was canceled, nailed to the cross. All of this imagery is covenant curse and wrath—not intimacy.

Yet simultaneously, reconciliation was accomplished. Second Corinthians 5:19 says, “God was in Messiah reconciling the world to Himself, not counting their trespasses against them.” Romans 5:10 says, “While we were enemies, we were reconciled to God through the death of His Son.” Colossians 1:20–22 says, “Through Him to reconcile all things to Himself, having made peace through the blood of His cross.” Ephesians 2:13–18 says, “You who once were far off have been brought near by the blood of Messiah.” First Peter 3:18 says, “Messiah also suffered once for sins, the righteous for the unrighteous, so that He might bring us to God.” At the very moment the Son was far, the worshipers were brought near. At the very moment wrath fell on Him, reconciliation opened to us. The veil of the temple was torn in two (Matt 27:51), and Hebrews 10:19–22 says this grants us confidence to enter by the blood of Yehoshua. The victim endured separation; the worshiper received nearness. This is the trade-off.

This logic answers every objection. When people say “separation isn’t biblical,” the verse arsenal above proves otherwise. When they point to Psalm 22:24 saying God did not hide His face, the psalm itself shows a movement from forsakenness to vindication, not a denial of forsakenness. When they worry about breaking the Trinity, Scripture itself holds the paradox of real forsakenness experienced by the incarnate Son with the triune unity of redemption (Heb 9:14). When they confuse discipline with propitiation, they miss the difference: God is close to the brokenhearted (Ps 34:18) and disciplines sons He loves (Heb 12:6), but wrath against sin is not fatherly discipline—it is judgment and curse. To conflate them is to miss the whole point of substitution.

The parallel to the lake of fire makes the distinction sharper. Second Thessalonians 1:9 says, “These will pay the penalty of eternal destruction, away from the presence of the Lord and from the glory of His power.” Revelation 20:14–15 speaks of the second death in the lake of fire, Revelation 21:8 of the final judgment on the wicked. Matthew 25:41 records the words, “Depart from Me, accursed ones, into the eternal fire.” This is eternal separation. The cross is the same in kind but not in degree. At the cross the wrath was concentrated, substitutionary, and exhausted. In the lake of fire the wrath is ongoing, retributive, and endless. The Son bore in hours what the lost will bear forever, and He bore it so we would not have to.

The altar logic ties it all together. The worshiper receives nearness; the victim bears judgment. Leviticus 1–7, 16, and 17 all confirm it. Hebrews 13:11–13 makes it explicit. Isaiah 53:10 says, “It pleased Yahweh to crush Him.” First Peter 2:24 says, “He Himself bore our sins in His body on the tree.” To say God was close to Him in wrath is to overthrow the very system God Himself instituted to prepare us for the cross.

Psalm 22 in full captures it all. It begins with forsakenness: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? Far from my deliverance are the words of my groaning” (22:1). It describes mockery, physical torment, pierced hands and feet, lots cast for garments. It shows the abandonment of God’s face. Then it shifts: “You have answered me” (22:21), “He has not hidden His face from him” (22:24). Finally, it concludes with global reconciliation: “All the ends of the earth will remember and turn to Yahweh, and all the families of the nations will worship before You” (22:27). In the same psalm, separation and reconciliation stand side by side. In the same moment of history, the Son is furthest from God while the nations are brought nearest. That is the paradox of the cross.

The conclusion must be clear. What really happened at the cross is not sentimental closeness, but wrath and reconciliation colliding in one moment. The Son bore the full weight of separation, curse, and forsakenness. The Father hid His face. Wrath was poured out in all its terror. At that same moment, through that same blood, the world was reconciled, the veil was torn, and the nations were invited into the bosom of God. Psalm 22 was not a decorative quotation but the Spirit’s chosen lens: forsakenness leading to vindication, wrath leading to reconciliation, curse leading to blessing, distance for Him leading to nearness for us. To preach it otherwise is not just error—it is misrepresentation of the Word of God. The altar, the prophets, the psalms, and the apostles all testify with one voice: wrath is separation, reconciliation is substitution, and the cross is where they meet. There can be no more confusion. The Messiah’s cry was real, His forsakenness was real, and our salvation is real because of it.